Featured Stories

Linda Hoover: I Mean to Shine

Considering all the systematic imbalances within our culture it surely isn’t much of a stretch relating to that great philosopher Randy Newman when he spits out the old saw about the world not being “fair.” That may very well be the case. But I’m here to tell you that, occasionally, there is justice in this world—you just need to be determined and patient enough to positively redress the situation.

Having watched the sun circle this planet for longer than half a century, it’s darn near impossible to be pleasantly surprised or shocked by life’s vagaries. But as with all things there are exceptions to the rule, and this year’s summer solstice is emitting spectacular fireworks: a stunning work of art is being unveiled after 52 years of gestation—a masterpiece from the shadows of 1970 has finally materialized. Its arrival fills a void I wasn’t even aware of. If the waiting is indeed the hardest part, it is high time for introductions to be made all around of this stunning maven of musicality by the name of Linda Hoover, and the remarkable album she recorded in the spring/summer of 1970 titled I Mean to Shine.

The surreal odyssey that led to the release of I Mean to Shine for Record Store Day on June 18, 2022, is beguiling for a number of reasons. Primarily, because at long last it brings Hoover’s world-class talents to a deservedly broader audience. But of equal importance, it gives music fans a deeper appreciation and understanding of the nascent origins of songwriter/musicians Walter Becker and Donald Fagen, who, along with producer Gary Katz, would achieve international recognition through their musical enterprise known as Steely Dan. Five decades later, with millions of recordings sold, thousands of accolades, a handful of Grammy awards, a dozen Top 40 singles and LPs, and an induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, Steely Dan is one of the most beloved and respected institutions in the history of popular music.

But in the years preceding the release of their debut album Can’t Buy a Thrill, in November 1972, Becker and Fagen were a couple of out-of-work schlubs, vainly attempting to penetrate the outer boroughs of the music business through their unconventional, yet highly original, stabs at songwriting. After decamping from their alma mater of Bard College in upstate New York circa ’68–’69, they made the acquaintance of Kenny Vance in the fabled Brill Building of Manhattan’s Tin Pan Alley (1619 Broadway on 49th Street). Vance was a member of Jay and the Americans, a cabaret act that scored a number of histrionic chart hits between 1962 and 1968. But by ’69 Jay and the Americans’ star was on the decent, and Vance shifted his focus toward music publishing and production work.

“Librarians on acid” was how Vance described the two introverted bohemian waifs when they showed up at his office one afternoon peddling their wares. At a time when no one else would listen to their material, Vance found the duo’s quirky compositions compelling, and he entered into a publishing contract with them. This arrangement generated a modest amount of pocket money to live on and allowed Becker and Fagen to record demos of their songs for potential use by other artists: demos that Vance held the rights to and would later license to various fly-by-night companies in the 1980s. Vance also provided the bassist (Becker) and pianist (Fagen) some steady income for nearly two years by enlisting them into Jay and the Americans’ rhythm section, supplying Becker and Fagen with an endless series of anecdotes in the years that followed, regarded as their “salad days,” when they cranked out renditions of “Cara Mia,” “Come a Little Bit Closer,” “She Cried,” and “Only in America,” every weekend for 50 bucks a gig. Becker and Fagen also wrote horn and string arrangements for JATA, receiving credit on the Capture the Moment LP and the “There Goes My Baby”/”Solitary Man” single. In early 1970, Vance hired Becker and Fagen, along with guitarist Denny Dias and JATA drummer John Discepolo to compose and perform as “The Original Soundtrack” for a low-budget film by novice director Peter Locke, titled You Gotta Walk It Like You Talk It or You’ll Lose That Beat. Declared a “genial put-down of the Establishment” by the New York Times, the film and its score were released in September 1971. Vance produced the music. Immediately after the film’s limited release it disappeared without a trace.

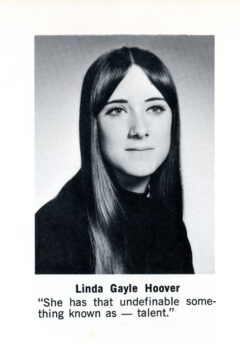

It was in this cultural milieu that Becker and Fagen met Gary Katz, an A&R man for Bobby Darin’s TM Music, who also had an office in the Brill Building where the three of them became fast friends. Like Becker and Fagen, Katz was a fast-talking hipster, who aspired to become an independent producer. By the end of 1969, Katz was inspired to collaborate with, and promote a young singer by the name of Linda Hoover. Katz first became aware of Hoover after winning a talent contest at the age of 14.

Wowed by the bell-like clarity of her rich soprano, Katz took the high school sophomore for an audition with music entrepreneur Morris Levy, a colorful character known throughout the industry as president and co-founder of Roulette Records. Levy was impressed enough to offer Hoover a recording contract, but her father insisted that she finish high school. When the family moved to Florida in 1969, Hoover enrolled in Jacksonville University but remained fixated upon a career in music.

Linda Hoover was born May 1, 1951, in Oakland, New Jersey. As the youngest of three children brought up in a music-oriented family, Hoover soaked up the immense cultural influences around her, including Broadway performances, popular music on the radio, and the singer-songwriters of the day. After her older brother Larry taught her how to play the guitar, she studied and emulated the compositions of Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell, Leonard Cohen, and Laura Nyro among others. It wouldn’t be long before her guileless nature and unblemished beauty drew attention to her innate talents as a vocalist.

As she later explained to Scott Schinder: “I only lasted one semester in college. I was very unhappy, and I called Gary from my dorm on one particularly difficult night. He told me to find a way back up to New York and that we would get a record deal. My father was trying to protect me, but I was determined to leave, and finally my parents had no choice but to let me go. Around Christmas of 1969, I returned to New York and signed with Gary’s production company.”

When Katz made the rounds among various labels on Hoover’s behalf at the beginning of 1970, it was Morris Levy once again who was the most enthusiastic about Hoover’s singing—enthusiastic enough to provide Katz with a “modest budget” and to give the green light for Hoover to record a full-length solo album. As one of Katz’s first productions, he knew exactly which musicians he wanted to enlist for the project.

In the spring of 1970 Becker and Fagen gathered with Katz at Advantage Sound Studios in Manhattan. Not only did Becker and Fagan play electric guitar, bass, and keyboards, they also chose the songs that Hoover would sing and wrote out the arrangements for the other musicians who would end up performing on the album, including future Steely Dan members Denny Dias on acoustic guitar and session guitarist Jeff Baxter, who also doubled on pedal steel. Drummer Discepolo was once again drafted in, as were members of the Dick Cavett Orchestra, providing strings, brass, and woodwinds.

Hoover: “I met Donald and Walter in the Brill Building and they asked me to sing my songs for them and wanted to know what my aspirations were. The next time we met was at Advantage Sound Studios, where I heard the songs I was going to record. I had no idea what they were doing with Jay and the Americans until I read about it later. At some point when we were recording the I Mean to Shine album, Walter played some of the tracks from You Gotta Walk It Like You Talk It or You’ll Lose That Beat for me. I was just blown away. Even as raw as the tracks were, it was not like any music I had ever heard. I loved it. The only thing said to Walter was that it reminded me of Frank Zappa’s music and I remember he liked that.

“I did not have any choice about song selection. I might have had a choice, but I recall being asked once and I was dumbfounded. I could not think of a thing! It was embarrassing. My mind went blank and that was that. I knew that I did not want to do songs other women of that era had done. I still have a thing about that when it comes to some artists and songs they have done. For instance, over the years people would ask me to sing ‘Me and Bobby McGee’ and I would never do it. How could I possibly sing that after Janis did it? No way. It was perfect the way she did it, and I would not begin to try.

“So, being totally in awe of Becker and Fagen, my mind went blank, thus they chose the songs. That’s how I remember it. They chose “In a Station” by Richard Manuel [from The Band’s Music from Big Pink], which I had never heard before, and that one turned out to be my personal favorite on the album. They also chose “4+20.” I was a fan of Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young and it was cool to be doing one of Stills’ songs. I loved the arrangement, which was upbeat in contrast to the sad lyrics. I have no idea how the Kenny Vance song, “City Mug,” was chosen for the album. What I do recall about it was how taken I was with Kenny’s gorgeous voice when he sang it to me. He was standing right in front of me singing and I was blown away by the beauty of it.”

In addition to those three titles, there are five Becker and Fagen songs, along with three of Hoover’s originals.

Hoover: “‘The Dove’ is a song I wrote when I was in high school about a guy I was in love with. ‘Autumn’ is another song from my high school days about a different boyfriend. Boyfriends were what it was all about! Ha!

“I wrote ‘Mama Tears’ a couple of days before we started recording and Donald wrote out the musical arrangement for it. I had left my parents’ home in Florida and moved up to New Jersey. I was waiting for Gary to call me into the City to start the sessions. I was missing my mother and ‘Mama Tears’ just poured out onto the paper. For me, some songs happen that way and others are more difficult to write. My parents lost my brother, who was hit by a car when he was six years old and remained in a coma for six months before he died. I was born two years later. My mother went through a lot in her life, but she did not let it keep her down. She had a great attitude and sense of humor, and one of the most beautiful voices I have ever heard in my life. I was blessed to have had her in my life. She passed on in her sleep almost five years ago and was singing all kinds of songs the night before. The nurses loved her.”

***********

Five stellar Becker and Fagen songs dominate side one of I Mean to Shine, and it’s curious to consider why, out of all the songs they had in their arsenal, they choose these five. The album asserts itself immediately with a title track that sounds like it could have been written specifically with Hoover in mind. Proud, clear, bold, and determined, it feels like we’re being set up for something epic, where even the sky’s not the limit. The lyrics hint at an acceptance of what has come before and a willingness to face your fears and embark on the journey ahead without looking back at the past.

Hoover: “I remember being in the studio once when the orchestra was there, and it was amazing. I can still recall [engineer] Mallory Earl setting up. It was a big deal in those days because if one note was out of tune or incorrect, the decision had to be made whether to let it go or cut and splice the tape. It was thrilling to see all of those people playing the songs. Donald wrote all of those scores out by hand and made copies for each player. That was a lot of work!”

Next up is “Turn My Friend Away,” where it sounds like the naïve optimism of youth is mutating into a certain blend of wisdom, laced with cynicism. The song’s stirring chorus is delivered with powerful authority by Hoover: “Well, I just wish I had a penny for every time I’ve heard those same empty-sounding words. They just fill the night with tears, like a snowbird that I hear singing at dawn: I know what he’s trying to say. As the night turns into day.”

Hoover: “‘Turn My Friend Away’ is a great song, too. Walter was so brilliant. People tend to talk about his angst and attitude, or things like that, but he had a kind and gentle side too. He also had a great sense of humor. Donald and Walter both had a tremendous ability to observe the human condition and skillfully write about it in their songs. At one time I remember Walter was toying with the idea of titling the song only ‘Tern.’”

Given the duo’s love of ornithology through their expressed devotion to Charlie “Yardbird” Parker, it somehow makes sense to want to name this song after a seabird. Additionally, “Tern” sounds like a stylistic prototype for the future classic “Any Major Dude Will Tell You.” Before you know it, the song ebbs into the distance, setting you up for the high drama of the next scene.

And man, what a stunner it is. They say you should lead with your strengths, but it may have been a miscalculation to place “Roaring of the Lamb” so early on the album, because its powerful intensity is difficult to match by the eight songs that follow. Every performance on this album is marvelous in its own way, but “Roaring of the Lamb” has something transcendently special about it, particularly if you’re at all familiar with the stripped-down piano and vocal demo that exists from the pile of Brill Building recordings that Kenny Vance supervised. Between the dynamic string-and-horn arrangement that Becker and Fagen came up with, and the over-the-top, kick-ass vocal performance from Hoover, “Roaring of the Lamb” leaves me shaking my head in disbelief every time I hear it. This is an absolute tour de force by everyone involved. Talk about being pleasantly shocked into speechlessness; it’s magnifique and beguiling, to be sure!

Hoover: “‘Roaring of the Lamb.’ Oh my goodness, what a song. Again, you have to interpret the lyrics for yourself, but there is that possible spiritual component. Is the ‘Lamb’ Jesus Christ, the Lamb of God ferociously roaring over man’s inhumanity to man? The war in Vietnam was so horrific and I think our generation was seeing the horrors in real time for the first time in our lives. Our fathers and uncles fought in World War II but to many of us that was the past and something we learned about in history class. In the 1960s and ’70s, we actually knew people who were being drafted—kids that we had gone through school with were dying there. Maybe it wasn’t spiritual to Becker and Fagen at all, but it was to me. And maybe it wasn’t about Vietnam, but that is what I thought about when I was singing it.”

On The Original Soundtrack’s version of “Roll Back the Meaning,” Kenny Vance handles the lead vocal. But Hoover was eager to do her own interpretation, and the track chugs along in a much superior fashion than the take on You Gotta Walk It Like You Talk It. Part of that is due to Katz’s pristine production, but also because Hoover’s vocal propels the song into an irresistible groove, along with Discepolo’s superb drumming.

Hoover: “‘Roll Back the Meaning’ was one of those great songs Donald and Walter presented to me and I loved it right away. Like most of their lyrics, and any of the cover songs I have sung, I have no idea what they were thinking when they wrote it. They were young too, and things were starting to happen in their careers. Maybe they could feel the ‘good’ coming on.”

The lovely “Autumn,” penned by Hoover, is a brief respite from the Becker/Fagen intensity, with Eric (“Dueling Banjos”) Weissberg providing acoustic accompaniment. “The only time I saw Eric Weissberg at the studio was when he played on ‘Autumn,’ says Hoover. “I had written it in a fingerpicking style and showed him what I was doing, and he took it from there—chewing gum the whole time—and played it perfectly the first time through.”

And then along came “Jones.”

Papa stashed it away and he wasn’t waiting for no rainy day

With a pool in our back yard and he never worked too hard

He was nobody’s fool and he sent me to a very private school

It was easy, it was fun, and one by one I let my days go by—gettin’ high…

Now the days of alms are past there’s no more rainbows to be had

I’m thinking of the days that used to be

But a monkey on a silver string ain’t really all that bad

Just wait until my jones comes down on me.

Do you recall the gallery, the writing on the wall?

All the words and the wine, me believing they were mine

Now the only words I hear say my dreams will disappear or turn to clay

And either way…

The days of alms are past there’s no more rainbows to be had

I’m thinking of the days that used to be

But a monkey on a silver string ain’t really all that bad

Just wait until my jones comes down on me.

One more lonely night and no one here but just myself to fight

And there’s nothing I can do my fighting days are through with you please

I’m on my knees…

Now the days of alms are past there’s no more rainbows to be had

I’m thinking of the days that used to be

But a monkey on a silver string ain’t really all that bad

Just wait until my jones comes down on me.

Allegedly, Becker wrote this meditation on addiction without Fagen’s input. Although Thomas Jefferson Kaye cut a version in 1974 for his First Grade LP, produced by Gary Katz, Hoover’s performance is superlative and spectacular, and it sounds like she’s inside the song’s character. The track is rich, dense, and full of pathos, concluding side one on a delirious note and providing a captivating glimpse through the shock corridor of the early Becker/Fagen cannon. Still, I find it difficult to imagine that Hoover had any first-hand experience with the denizens of the drug world.

Hoover: “Addiction is a terrible thing and the lyrics to ‘Jones’ tell it like it is. The song has a great hook and melody and people love it, but when you think about the lyrics it is such a sad song. When I was singing it, I did not personally know anyone who was drug addicted, or if they were I did not know it. I knew about famous people and great musicians who had succumbed to it. Thankfully, I was not ever exposed to those hard drugs. I am personally so tired of losing people to drug addiction. It is so brutally sad. This fentanyl thing is terrifying to me. I worry for the young ones who are just looking for a good time and end up in the morgue. We have lost too many talented musicians, young kids, and people in general to drug addiction. It is tragic.”

***********

While there is a distinct difference between the two sides of I Mean to Shine, it all weaves together seamlessly as a whole, thanks to Becker and Fagen’s arrangements, the inspired performances by all the musicians, and Katz’s cohesive production. But what really holds it all together is Hoover’s pure and powerful vocalizing throughout all 11 songs on the album.

The one song that Becker and Fagen did not arrange was “In a Station,” with Denny Dias contributing a sublime horn arrangement to the Richard Manuel classic. Even without knowing the backstory to “Mama Tears” it is a stirring performance brimming with emotion, driven home by a superb arrangement. Some well-needed levity is provided by the Vance/Lifschutz hoedown of “City Mug,” before another shot of pathos is delivered by a sincere reading of Stephen Stills’ “4+20.” The album concludes with Hoover’s composition “The Dove,” and by the time she is done trilling her way through this folksy tone poem, I feel like I have been delivered to a place of contemplative beauty. Do you enjoy the stillness left in its wake? Or do you flip the platter and take the ride all over again? I guess that all depends on how late in the evening it is.

***********

If you listen to the production choices that Katz makes on I Mean to Shine and compare them to the choices made by Vance on You Gotta Walk It Like You Talk It, their approaches to the material, both sonically and aesthetically, are worlds apart from one another. And just because this is only Katz’s third or fourth production gig it still manages to sparkle like the work he would become famous for with every Steely Dan album that followed, including Donald Fagen’s solo masterpiece from 1982 The Nightfly.

There is a Becker and Fagen song on Steely Dan’s debut LP called “Kings,” which contains a refrain with ironic overtones: “He meant to shine, till the end of the line.” In a song that evokes the ghosts of Kennedy and Nixon, it’s also a deliberate callback to their project with Linda Hoover.

After Katz and engineer Mallory Earl mixed the eight-track master down to stereo, the legendary Joel Brodsky was hired to provide images for the album’s cover. Famous for his iconic cover portraits of The Doors, Strange Days, The Stooges, Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks, Funkadelic’s Maggot Brain and Free Your Mind…and Your Ass Will Follow, not to mention the debut album by Kiss, Brodsky produced some fabulous head shots of Hoover and her glorious, wide-eyed innocence.

Hoover: “Mr. Brodsky was very nice to me and super professional. He also took photos of Donald, Walter, and me walking down the sidewalk in the city, but those photos have not turned up as far as I know. One thing I remember was that I was uncomfortable because I did not know how to pose—but nothing about that has changed in all of these years!”

Katz declared the project complete and when he took the final mixes to Levy, he was told, “You did a great job. I love the album.” But when Levy enquired about the publishing rights to the album’s 11 songs, Katz responded that other than the three Hoover originals, all of the other songs were already assigned to their respective publishers. When a conversation between Vance and Levy yielded no compromises by either party, Levy decided to shelve the entire project. “He wanted to own the publishing, which I couldn’t give him, so it was as simple as that,” said Katz. “Morris and I always got along and he liked me, thankfully, so he was nice about it. But there was nothing more we could do because he owned the record. And that was that.”

When Vance broke the news that the project had been shelved, Hoover was understandably “disappointed and heartbroken,” finding it impossible to bounce back from this devastating turn of events. When she found out the title track to her abandoned album was going to be recorded by none other than Barbra Streisand for her Barbra Joan Streisand album, it was another indignity she found difficult to endure. However, she still managed to collaborate with Katz on one more project before moving back to her family in Florida, recording a demo of the Katz-penned “Cody Canyon.”

Hoover: “The song ‘Cody Canyon’ was written by Gary Katz around the time they went out west and recorded with Barbra Streisand. As you can imagine, I was crushed by my album not being released and had returned to Boston where I was living part of the time. Mallory Earl, the engineer on I Mean to Shine, came to see me in Boston and told me that Gary was starting a new project with Donald, Walter, Denny, and Jeff, and wanted me to come join them to record a song. I went to NYC and we rehearsed the song ‘Cody Canyon.’ I don’t remember who the drummer was, but I think it may have been Mallory. Gary was the lead singer and I sang backup. We went to Boston to record the song at Amphion Studios and returned to NYC to showcase ourselves. We played for some people. I am not sure who they were, but they did not pick us up. That is the only song I remember playing for them. In the meantime, Gary had little children and a wife, and needed to work. The opportunity to join ABC Records in California opened up and he went for it. He asked me to go with them but I felt defeated and declined the invitation. Jeff Baxter tried to convince me to shake off the loss of I Mean to Shine, but I couldn’t. I have no idea if the demo of ‘Cody Canyon’ exists. I did not get a copy of it.”

Having her dreams dashed by this turn of events, Hoover returned to her family in Florida—but not before securing a reel-to-reel copy of the stereo mix down for I Mean to Shine, where it languished in her possession for the next 50 years.

Hoover: “I never returned to college. Over the years I have had people ask me if I would teach their children how to sing or play, but I am self-taught and I do not read music, so I never thought I had the credentials to teach anyone. I would encourage anyone who is serious about a career in music to go and learn the full scope of it. When my son Toft started writing songs in elementary school, we knew he had a gift and would need good teachers. When he was in high school and decided that he wanted to be a singer-songwriter, I told him that I wanted him to know his art well and to go to the best school we could find for the type of music he was writing. My experience in NYC working with professionals taught me a lot about how important that is.

“After I met my husband, Jay, I followed him to North Carolina while he attended Duke University. I worked the front desk in a hotel there and played at a club in Chapel Hill. We married and he attended the University of Florida for five years as an undergraduate and law student. I worked on the campus and on weekends I played gigs in the area. When he graduated, we went to Orlando and I worked in venues around there. We started a family and had our sons James and Toft. Jay and I sang in the church choir, and I was in a band for a while called Max Dagger. We practiced in our living room, which the neighbors were not happy about.”

Jay Willingham: “I have been practicing in Florida mostly as a sole proprietor since 1978. In that time, I have practiced many kinds of law. However, the reason I went to law school was to help Linda. So, entertainment law has been my love since I read about it in Clive Davis’ book in our apartment in Gainesville, Florida, in 1973 or so, when I was still a premed student. Since my law school days I continue to practice in the area.”

When the unbelievable story of I Mean to Shine began to circulate over the past few years I had an image of the ¼ inch, two-track tape dub languishing in a closet for 50 years until that “aha!” moment when it was understood by Linda and Jay that they were sitting on an artifact of priceless historical and artistic importance. I wondered if the two of them ever revisited those tapes?

Hoover: “There were two boxes of tapes that I brought back with me when I left NYC: side A and side B. Bob Yeomans was a friend who worked at Advantage Sound Studios, and he knew how to run the machines. I thank God that Bob had the idea to make me the tapes. It never occurred to me that I should have a copy to show what I had done. When we found out that the album was not going to be released, Bob had the foresight to make the dubs before the masters disappeared. I met my husband, Jay, shortly after I got back to Florida, when he was at a performance I did at a local college in Orlando. Jay was starting a band and he wanted me to join them. We got married and for the next five years he was in school. I sang in local clubs and worked on campus. Jay was practicing law in Orlando, including entertainment law, and had done work for various artists and studios in the area. By that time Steely Dan had become popular and Jay’s interest in the album that I had done with them led him to have the old tapes restored. He gave the I Mean to Shine tapes to an engineer he had developed great trust in, Andy DeGanahl. Andy baked the old tapes and converted to digital everything I had recorded on tape up to that point. The old I Mean to Shine tapes had a lot of pops and clicks or whatever they call them, wobbles, etc., due to the age of the tapes, but at least we had preserved them.

“You asked if we played the original tapes. We did, but not often. Jay wanted to keep the old tapes in the best shape possible. We continue to search for the original eight-track and two-track masters. Of course, once the tapes were baked and transferred to digital we never used them again.

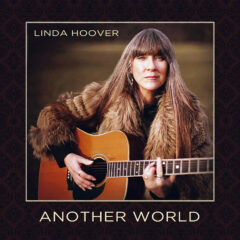

“I want to mention that our son James is a computer animator and Previs supervisor with Third Floor in Los Angeles. He has worked on many major films and, along with his brother Toft, encouraged us to preserve all of my recordings, understanding their value. Our son Toft went to Berklee College of Music in Boston, and one of his degrees was in music production and engineering; he assisted in removing the pops and clicks from the music, along with engineer Rick Carson. Toft lives in Los Angeles and is a producer, songwriter, vocalist, and guitarist. He is a prolific writer and toured with his band Spiritual Rez for ten years before settling in LA. Toft produced my album, Another World, in 2018.”

Timing is…everything

Once they cleaned up the source tapes for I Mean to Shine, Hoover and Willingham sought to find a label interested in releasing and distributing the album. After making inquiries at Warner Music Group, who had acquired the Roulette Records back catalog, the couple’s son Toft played the restored tapes for David Ponak at Rhino, who immediately suggested talking to Cheryl Pawelski, the owner/operator of Omnivore Recordings. Pawelski and her staff have been churning out a steady stream of prestigious archival projects for over a dozen years, earning Grammy awards and other nods within the industry for Omnivore’s conscientious treatment of priceless music history. Hoover says that Michael Graves at Omnivore “took the restored tapes and remastered them to make the album sound almost as good as the original multi-tracks—Graves is awesome.” Pawelski began working on I Mean to Shine in May 2021 and decided to wait for this year’s Record Store Day in order to give the release greater visibility.

Pawelski: “I wish there was a more comprehensive look at Becker and Fagen’s formative years. But it is really nice to add this piece to that chapter, because think about how distinctive the sound is, right? When I first heard I Mean to Shine there was just a certain point when listening to this record where everything…all of my auditory senses pricked up because I was like ‘Oh my God! This is Steely Dan.’ [laughs] I was overly impressed with the whole thing and it really is a revelation.”

I wonder aloud if there are aspects of the I Mean to Shine project that could be considered a put-on or an in-joke among our intrepid hipsters? Pawelski doesn’t think so. “I wouldn’t necessarily read it that way. I think Becker and Fagen are probably just trying to make a great record. I think that what we impose on them—what we think their personalities are and how it extends into their professional record making…you gotta remember that these guys are at the beginning of their career. They’re probably doing the best that they absolutely can.”

Pawelski concludes by saying that a project like I Mean to Shine “is my favorite thing to do: to either add a page or a chapter to an artist’s legacy. And this one is adding a couple of pages to Steely Dan and a whole chapter for Linda. And it’s just a honor and a pleasure to be able to do that.”

After the release in 2018 of her CD, Another World, it is clear that Hoover is no longer the choir girl of 1970. But as a mature woman in the here-and-now, her voice and presence have not withered one whit. In fact, I’d venture to say that Hoover’s musical voice is more powerful than ever before. Sometimes experience does translate into wisdom.

Hoover: “The most significant thing I have learned over the 52 years post-I Mean to Shine is that giving up on a dream will never accomplish a thing, other than to keep you down in the pit. It is a long story, where I became very depressed. I lost faith in myself even though I had faith in God. Music was not fun anymore.

“What I can tell you from my current perspective is that allowing yourself to be beaten down or, worse, beating yourself down, wastes the precious days that we are alive. Being positive is a choice we have the power to make. When we are young we sometimes tend to think we have all of the time in the world. But that is not the case. That is essentially what Jeff Baxter was trying to tell me when I refused to go to California with Gary and the guys. He was trying to tell me to shake it off and move on. The music business is like all businesses. If you don’t take care of your work and do what needs to be done, regardless of your ‘feelings,’ your business will not survive. Almost everyone who is successful will tell you that they have been knocked down a time or two. I wish I had known in 1970 what I know now. Not everyone in my life was excited about the music business, expressly my parents and my husband’s parents. I didn’t know who to trust. I turned the shelving of I Mean to Shine on myself.

“You know, I want to express that if you love something and you have the ability to do it, just go ahead and do it. Because it will drive you crazy if you don’t. Don’t stop to look back. Keep moving forward. My husband says you can’t plow a straight row if you don’t keep looking forward. In living everyday life, you might as well expect to make mistakes or get knocked down sometimes. So what? Just get back up. I had so much unrealistic expectancy when we did I Mean to Shine. It never occurred to me that it might not be released. I lost many of my friends because I was ashamed to face them. I thought that I had failed.

“My point in all of this is to encourage people to forget all of the stupid stuff and just play. Just sing. Do it because you love it and because you have a gift to share with people who love music. Ignore the negatives but be willing to take constructive advice. We have all heard of ‘mood-altering’ substances. For me, music is a mood-altering gift. We all have music that brings us up when we hear it. Steely Dan brings me up every time because it is so musically delicious and lyrically spot-on. I know now that I have got to keep moving forward or I will miss the adventures ahead. The release of I Mean to Shine is a life lesson for me. I never thought I would see it. Were it not for my husband and my sons moving me forward, it might never have happened. I may be 71 years old, but I am determined to play and sing as long as I possibly can, like my sweet mama did, because it makes my life better and, hopefully, will touch someone else in a positive way.”