Yesterday And Today

The Roots of Hawaiian Music: Slack-Key Guitar

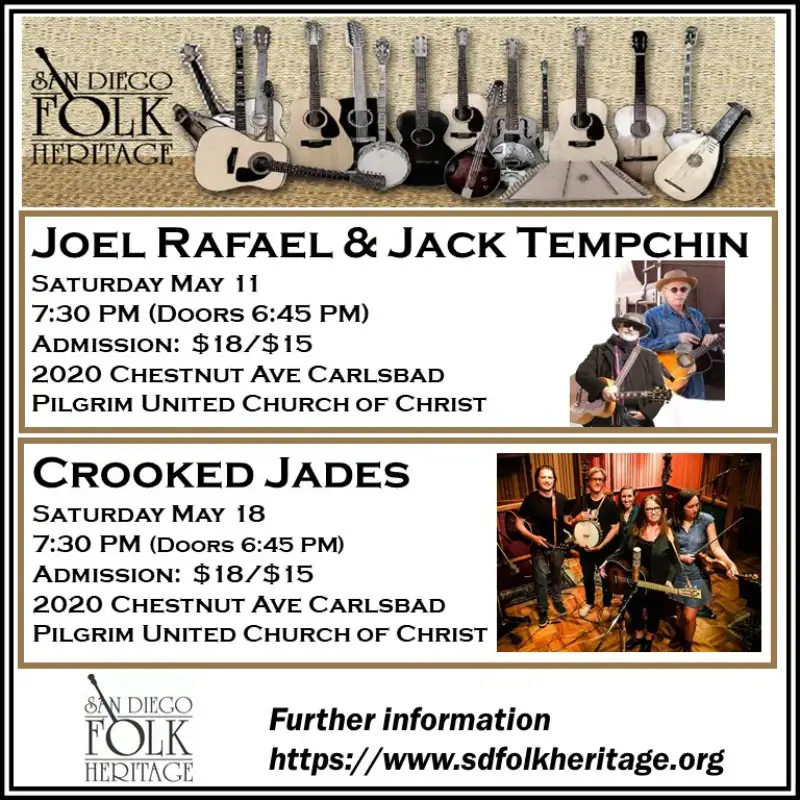

George Kahumoku Jr. Photo by Matt Thayer.

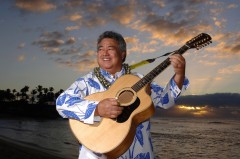

Gabby Pahinui

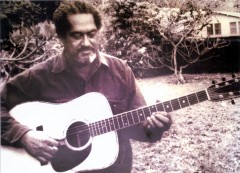

Bing Crosby had a hand in popularizing Hawaiian culture during the 1930s

Queen Lili ‘uokalani, the last Queen of Hawaii

While Hawaiian music has become mostly overlooked in Americana-roots music culture, it has influenced rock, blues, folk and country music on the mainland over the last century with its emphasis on passion, melody, lap steel guitars and ukuleles. Today, George Kahumoku Jr. represents a kind of embodiment of Hawaiian culture and its awakening over the last century. He is a slack-key musician with a voice as pure as a Pacific wind, a poet, a farmer, a sculptor, a teacher, a self-styled philosopher and a published author. On Wednesday and Thursday nights he presents the Masters of Slack Key series at Napili Kai Beach Resort in Maui, bringing slack-key greats like Jeff Peterson, Cyril Pahinui and Led Kaapana to the concert stage. Probably most notably for San Diego is George’s first mainland concert was at Humphrey’s in the late ’80s. He is in the midst of a Kickstarter campaign to produce a documentary film series titled The Masters of Slack-Key Guitar. Much of the information garnered for this brief glance at Hawaiian music is the result of interviews with him.

Along the islands known today as Hawai’i, where the ocean meets the shore, for many generations — too many to count — the troubadours of the isle muse have met the coastal magic of tide and wind. For centuries they created their own unique waves of chants, melodies, and harmonies that flowed nightly like the ocean that surrounded them.

George Kahumoku Jr. describes Hawai’i as a “canoe” culture. The people of Hawaii came to the island by canoe, bringing their culture with them. That canoe has traveled along a river of music. It’s one that began so long ago there is no recorded history of its origin. We do know, like all people of great civilizations, there was a longing in the people to create and celebrate. This gave birth to the art that became the life-blood of Hawaiian culture.

Their first instruments were their native voices speaking through oral history — clothed chants to their ancient gods — they told the stories of their ancestors. The monarchy was central to that history. Their King and Queen were the embodiment of the spirit of the history of the people. They kept their legacy alive in this way. It was through chant or mele and the sacred dance of the hula accompanied by the rhythm of the pahu, a sheep skin-covered drum, that they framed all of their passages of life.

When the American and European missionaries arrived in the late 18th century, the Hawaiians brought melodies and harmonies into the canoe. Their voices danced with joy through the high falsetto vibration that seemed to come from their deepest hearts. Melody may have been introduced to them by missionaries, but what they created belonged to the islands. The music brought peace and comfort to the people of Hawaii. It also attracted the outside world.

As foreign settlers in the 18th century moved to the islands, the banks of the river of music were broadened. The canoe gathered more treasures as the culture changed with outside influence. With the help of the Spanish and Mexican cowboys, known as Panoplies who came in the late 19th century to teach ranching skills, they learned stringed instruments and romantic ballads. Slack-key artist, Jim “Kimo” West says the music was so gentle and soothing, it was used in the evenings to calm the cattle. This was when the Hawaiians learned unique tunings, which came to be known as slack key. Today, it is known as a finger-style genre that uses open tunings. In Hawaiian it is called kÄ« hÅÊ»alu, which is translated “loosen the tuning key.” As the ranches around the countryside grew, each family developed their own unique and secret tunings. If the foreign cowboys brought the instrument and technique, the Hawaiian musicians gave the music its own unique sound. Slack-key guitar was then brought into the sacred circle of the mele-chant, the hula-dance, and the pahu-drum. These traditions were handed down from generation to generation. More stringed instruments came through other cultures most notably the ukulele, which was imported, thanks to Portuguese immigrants who came to work the sugar plantations.

But, even as the flow of the canoe along this harmonic musical river created peace, the political and economic rumblings of the late the 19th century served to nearly destroy all that had grown over the centuries within the Hawaiian culture. With the annexation of Hawaii by the United States in 1897 came the suppression of native Hawaiian culture, including the language and ancient traditions like the music, mele, dance, and most significantly the monarchy landing Hawaii’s last queen in under house arrest in the palace in Honolulu .

For 70 years the canoe was stranded as the native people were enculturated into North American ways in education, politics, government, and religion. But, the canoe still moved and gathered treasures. In the early 20th century, ragtime music fused with Hawaiian culture to create music that became phenomenally popular on the mainland. It came to be known as hapa haole or “half white” music. Artists like Rudy Valle and Bing Crosby would serve to create an illusion of Hawaii that boosted tourism. The earliest hapa haolie hit song is documented as “My Waikiki Mermaid” written by Albert “Sonny” Cunha in 1903. All the while, Hawaiian musicians were learning — instruments in hand and adding to the canoe as it continued down the river, unphased even by cultural oppression.

With the emerging Civil Rights Movement on the mainland in the 1960s came an interest in the renewed identity of the original Hawaiian culture. This became known as the Hawaiian Renaissance, which was a peaceful internal revolution. And the primary pathway for this cultural overthrow was an impassioned renewal of the Hawai’ian language and the re-emergence of slack-key guitar, the songs drawn from the ancient chants, and the re-institution of Hula as an important part of family, community and continuity of the history of Hawaii. It seemed to be most clearly defined in the now internationally famous Merrie Monarch Festival of Hula.

But, for a cultural movement to grow, it needs its champions, its heroes, its icons. If the folk music revival the ’60s had Bob Dylan and jazz had Miles Davis, then the Hawai’ian Renaissance had slack-key legend Gabby Pahinui. While he rose to international importance during the 1970s, Gabby was a local celebrity and a well-kept secret for many years before. Born and raised in the impoverished Kaka’ako area of Honolulu, he became proficient on the Hawaiian steel guitar before mastering slack key. He was musically active when the steel guitar was invented in Hawaii. He was also there when amplifying the instrument had a key influence on the invention of the electric guitar. Gabby’s earliest recordings are said to be in the late 1930s to mid-’40s. However, by 1970, he easily became one of the fathers of the Hawaiian Renaissance with a legacy of music to draw from. In the early ’70s he was respected in the world of roots music, even boasting a young Ry Cooder in his Gabby Band. He was revered like few others in Hawaii. But, his life was ended tragically short at the age of 59 due a heart attack.

Later, he would be immortalized by a legendary recording Hawaiian artist, Isreal Kamakawiwo’ole’, when at the beginning of his blockbuster hit, “Somewhere Over the Rainbow/A Wonderful World” he is heard to say, “This one’s for Gabby!”

Gabby Pahinui brought with him younger artists who today carry the standard of the continuity in excellence in slack-key music. It is now included with the songs and hula at festivals throughout Hawaii and internationally with Halaus (Hula schools) growing out of Japan, China, and Europe.

Among the younger performers who woke up to their culture during the late ’60s was George Kahumoku Jr. During my recent interviews with him he described first reading the history of the Hawaiian monarchy and the annexation in the late ’60s. He said when he read the autobiography of Queen LiliÊ»uokalani, the last Queen of Hawaii, late at night by firelight, he wept.

During his life time he has survived near death as an infant, shark attacks, and cancer. However, it has all served to strengthen his resolve to live a full life energized through his love of music, his people, and the land. He is a walking history of the spiritual awakening of Hawaii. He is one of the artists and key figures in his homeland who can faithfully steer the canoe through rough waters sometimes, but always into the light of the love that only good music can bring to the world.

Today, he runs his own three-acre self-sustaining farm with his wife, Nancy. He grows fruit,vegetables, and dry-land taro. He also peacefully tends goats, chickens, ducks, and miniature horses. He has taught music at local high schools and now also teaches guitar at a community college. With all of this, he has managed over the last decade to win three Grammys for regional roots music with a multiple volume slack key anthology album series.

The canoe that is Hawaiian music now continues to flow with the integration today of hip-hop, rap, and Jamaican music (Jawaiian). With many of the artists who came of age during the Hawaiian Renaissance of the 1970s growing older, the natural desire to pass the legacy along has grown. George Kahumoku has his eye toward passing the torch with his developing film series funded through Kickstarter. With director David Barry, he has completed two films in the series; Seeds of Aloha, Richard Ho’opi’i: The Timeless Voice and Dennis Kamakahi: The Legend of Grey Wolf. The current fundraising campaign is intended to complete two more chapters in the series featuring artists Martin Pahinui, Gabby’s son, and the Father of Jawaiian, Brother Noland.

With completion of these films and wider exposure of the roots of Hawaiian music, the legacy that has been handed down now for countless generations will continue. It’s easy to imagine the passion of the earliest Hawaiian ancestors and hear the soulful song in the wind that has been handed down as you listen to the songs of George Kohumoku and Gabby Pahinui. It’s the hearing that brings about the knowing that the canoe will continue to flow down this gentle river of music.

For a little taste of Hawaiian slack-key guitar this month, check out Led Kaapana on April 17 at AMSD Concerts, Sweetwater High School, 2900 Highland Ave., National City, 7:30pm.