Recordially, Lou Curtiss

Sam Chatmon, San Diego Bluesman Talks with Lou Curtiss

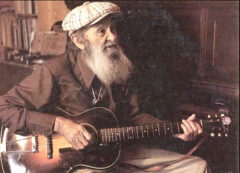

Sam Chatmon was one of the most remarkable individuals I have ever known. During the years he spent in San Diego (1966-1982, where he became an important part of the blues scene), I had a many chances to sit and talk with him. This excerpt is taken from one of those conversations.

I was born in 1899 at a little place between Jackson and Vicksburg, Mississippi, called Bolden, at a man’s place called John Gaddess. There were so many of us in the family then. My Daddy [Henderson Chatmon] had had three wives and my mother had the least [amount of] children of any of them, which was 13. Daddy said he had 60 children with the three wives, but that ain’t counting Charlie Patton and all of them on the outside. Papa died in 1934 when he was 109 years old. My grandmother lived to be 125. She said she’d come from the place where they’d caught the slaves on the Niger river. She said, “They’s put molasses out and catch them and herd them into a boat.” My Daddy was a fiddler in the slavery time, too, and when we kids messed off he’d tell us about how it was in them days. I remember once going out and playing music at night, and the next morning my brother Bert asked me how much I had made. I complained that I didn’t make nothing but a dollar and a half. Daddy’d yell out, “Well you ought to be happy; I had to play every night and didn’t get nothing but a whipping.

They used to have long troughs just like you’d have to feed hogs out of and would give you cornbread with as much rat fertilizer in the meal as there was corn. They’d put that old black bread in those troughs for the little children and make them eat out of there just like the hogs. They’d grease their mouths every Sunday with a meat skin on a string. My Daddy would always linger behind and try to get that meat skin, because it would be the only meat he could ever get. Every morning before they left the house, they’d have to come up to the master with a strap and let her whup them. Then she’d say, “You all be good little children. Go ahead now and get your breakfast.” And they’d line up at the trough.

My Father would play music with old Milton Bracy, just two fiddles and no other instruments. He didn’t play no music like we played, but just those old breakdowns: “Old Grey Mule,” “Chickens in the Breadpan Kickin’ Up Dough,” “Hen Laid the Eggs,” and all them things.

Can’t get the saddle on the old grey mule

Can’t get the saddle on the old grey mule

Whoa! Whoa!

Can’t get the saddle on the old grey mule

He had whiskers down to his waist and sometimes he’d have to tie them to the side with a cord to hold them off the fiddle. He didn’t play too much by the time I was around but if my brother Lonnie wanted Daddy to play, he’d just start fiddling one of his old tunes. Then Daddy would say, “Boy, that ain’t no way to play it, bring that violin here and let me show you how.” Those old square dance tunes took a bow arm to play, but these blues and things take a pull. Lonnie had learned to play the fiddle by reading the music. He was the only brother that could read. When the white folks wanted us to play something, they’d buy the sheet music in Jackson and give it to us. Then Lonnie would tell us all our parts and it was like we’d known it all our lives.

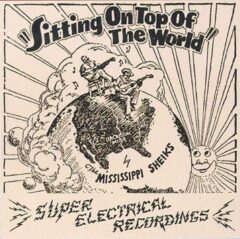

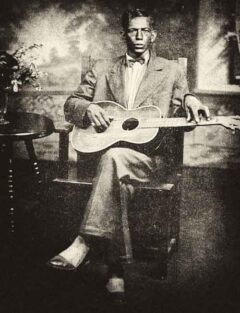

Music was just a given thing in our family. I got it from watching my brothers. It’s just like driving a car. You sit next to somebody and watch what they do and you can do the same thing with a little practice. If you ain’t got nerve to try it, you can still make a little stab. My brother’s and sisters all played; my Daddy and Mama, too. My cousins the McCoys [Joe and Charlie] and the McCollums [Robert, who later became Robert Nighthawk] all played too. We all played so many pieces, I could be here several hours just listing them for you. I wrote the words and Lonnie wrote the music for several of our best known tunes like “Ants in My Pants,” “Sittin’ on Top of the World,” “Stop and Listen,” “Corrina Corrina,” and “Pencil Won’t Write No More.” We also did all the old blues and written songs from the sheet music like “Alberta,” “Sheiks of Arabee,” and “Sleepytime Down South.” I started playing guitar when I was four years old. Even before I started to play I remember my older half brother Ferdinand [who made records under the name Alec Johnson] and Charlie Patton singing about the first blues I ever heard, something about “going down to the river” and “if the blues don’t leave me I’ll rock away and drown.” The first tune I learned to pick was “Make Me a Pallet on Your Floor.” Me and Lonnie put that out later as “If You Don’t Want Me, You Don’t Have to Dog Me Around” and folks thought it was a new tune that I’d got out. I’d sing a verse and then holler, “Oh, step on it,” and Lonnie would get out on that fiddle.

When I was seven, I started playing bass viol with my brother Lonnie—bull fiddle they called it then. I had to carry a box along so I could reach it. I didn’t see no banjos until I was 18 in Memphis. I picked up the tenor banjo then tuned it like the first four strings of a guitar. All of us nine brothers played together. Lonnie and Edgar played the violins; Harry played guitar, piano, or violin; Willie and Bert played the guitar; Bo played guitar, banjo, and sometimes violin; and brother Laurie played the drums. I usually played the bass and sometimes guitar. Our cousin Charlie McCoy often joined us on the mandolin and sometimes his brother Joe came along too. Neighbor Walter Vincent joined us in 1921. We usually called ourselves the Mississippi Sheiks but sometimes in different groupings we were Chatmon’s Mississippi Hot Footers” and often just Lonnie and I would go out [sometimes joined by Charlie McCoy] as the Mississippi Mud Steppers.

We used to play in the white folks’ houses or halls. Sometimes we’d play for a white man at a dance for three hours at six dollars per musician and then work 15 hours in the field for the same man for 50 cents the next day. When we put on a dance for our own people, we’d rent the hall for two dollars and charge them two bits at the door to get in. But mostly we’d work the white folks’ dances.

The only other band around was the Carter Brothers and Henry Reed. Lonnie sometimes played with them because he didn’t like to farm. The rest of us brothers planted a crop every year and when we were working out crops, Lonnie’d go over to Raymond and play with the Carter Brothers. I don’t know any other bands around there then and we were the main band people would call.

We used to play all the time at Cooper’s Wells and at Brown’s Wells where the healing waters were. That’s right near the county seat of Hiche County. Even after I moved to Hollendale in 1928, I’d leave off all the time to play for those people. They usually didn’t have much more than 35 couples there; that’d be about all you’d have. Sometimes we’d play for square dances too. In fact, the last dance we did was a square dance [shortly before Lonnie and Harry died]. It was at a hall built over the back of the Sunflower River below Hollendale. They were passing around whiskey in molasses buckets there. We never called the dances; a white man in a long dress coat and a fancy cane would do that. I always liked the blues, foxtrots, and one-steps the best, because on a square dance you’d never get a chance to change chords. Sometimes those tunes would last for a whole hour and just when you thought it was over, someone would call, “Promenade to the bar treat all the women folks to a drink,” and then we’d have to start back again.

In 1928, we went to Atlanta and recorded for a fellow named Brock. He’s come out to our place and found us there and asked me, Lonnie, Bo, and Walter to go. He didn’t want no bass fiddle so I played guitar. That’s where we first used the name the Mississippi Sheiks as we were all from Bolden, Mississippi. They gave me 20 dollars and Lonnie, Bo, and Walter 30 dollars each and no royalties. That’s the time we put out “Stop and Listen” and “Sittin’ on Top of the World.” Bo changed his name to Carter so he could record separate from us. This guy Brock had him under contract. Later on, my brothers Lonnie and Harry did the same so they could record separate too. Walter Vincent became Walter Jacob for the same reason. I never changed my name for any reason except at birth. I was named “Vivian” and I changed it to “Sam” because that was a girl’s name and I didn’t want to be named after no woman.

The next time I recorded was in Jackson and that was the time all of us brothers were there: Bo, Lonnie, Harry, Seth, Edgar, Willie, myself, and Walter Vincent, Charlie and Joe McCoy were there with Memphis Minnie. I did some duets with Bo and also a couple with Charlie McCoy [Charlie and I had been playing out as a duet in that time]. I didn’t go to a session again until 1936 when Lonnie and I recorded as the Chatmon Brothers for Bluebird. After that I was going to record for a man by the name of Williams in Chicago but he tried to beat me out of some money and blackmail me because I didn’t belong to the union. So I told him, “I ain’t got nothing to do with you.”

In the year of 1937 I lost three brothers (including Lonnie and Harry) and two sisters and after that our band didn’t play together. Also my picking partner, Charlie McCoy, moved on to Chicago to join his brother’s band (the Harlem Hamfats). I took up picking some with Eugene Powell (AKA Sonny Boy Nelson) but I never did any more recording. I kept farming til 1950. I rented that land and worked it ‘til I quit with my own team and all. Then I went to work as a night watchman and bought me a house and a half acre. I didn’t play much music until 1965 when Ken Swerilas [a San Diego record collector] came by and talked me into coming out to California to play.

Note: Starting in 1966 Sam started coming regularly out to the West Coast, where he became part of the regular lineup at THE SAN DIEGO STATE FOLK FESTIVAL in 1969. He remained a part of that festival until 1982. During that time Sam made new recordings for Blue Goose, Rounder (which I had the honor of co-producing) and Flying Fish (he also recorded sides that appeared on collections from Advent and Arhoolie and there was an LP on an Italian label recorded by a couple of Italian collectors in his hometown of Hollendale). Shortly before his passing Sam took part in a series done by Alan Lomax called “Confessions of the Noble Old” for PBS television. He died in 1982.

Reprinted from the San Diego Troubadour, May 2011.