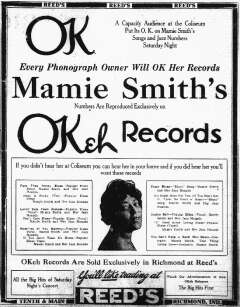

Black history on record started with orchestral and gospel music by groups like the Fisk Jubilee Singers, Jim Europe’s Military Band, and vaudevillians like Bert Williams, but black jazz started with Mamie Smith’s Okeh 4169 “Crazy Blues”/“It’s Right Here for You.” Both songs were described on the label as “Popular Blue Song”; the time was November 1920. The record sold pretty well and it became apparent to the record companies that there was a heretofore untapped market—the black record-buying public forming about 10% of the total population. Within a year three major record companies—Okeh, Paramount, and Columbia—started black music sections advertised as “race records.” A fourth major company, Victor Records, entered the market in 1924.

Black history on record started with orchestral and gospel music by groups like the Fisk Jubilee Singers, Jim Europe’s Military Band, and vaudevillians like Bert Williams, but black jazz started with Mamie Smith’s Okeh 4169 “Crazy Blues”/“It’s Right Here for You.” Both songs were described on the label as “Popular Blue Song”; the time was November 1920. The record sold pretty well and it became apparent to the record companies that there was a heretofore untapped market—the black record-buying public forming about 10% of the total population. Within a year three major record companies—Okeh, Paramount, and Columbia—started black music sections advertised as “race records.” A fourth major company, Victor Records, entered the market in 1924.Paramount (New York Recording Laboratories, a subsidiary of the Wisconsin Chair Company of Port Washington, Wisconsin) started a race series, their 12000 series, in mid-1922 with the first releases featuring artists like Alberta Hunter, Monette Moore, and Gladys Bryant. Paramount, like Okeh, recorded in New York City.

Columbia (Columbia Gramophone Company, New York City) led the way with their releases on the popular A3000 series of such artists as Mary Stafford and Edith Wilson. With their two heavy hitters—Bessie Smith and Clara Smith—leading the way, Columbia emerged as a major blues label. They started a 13000 race series at the end of 1923 but switched to 14000 after eight issues, because of the buying public’s fear of the number 13.

The big three dominated the market, accounting for more than two thirds of the total blues and gospel releases. However between 1921 and 1926 race records were issued on more than 15 different labels, such as Emerson, Pathe/Perfect, Arto, Cameo, Black Swan (acquired by Paramount in April 1924), Edison, Gennett, Ajax, Brunswick, and Aeolian’s Vocalion label (sold to Brunswick in late 1924).

Between 1923 and 1926, the great majority of blues records came from professional singers who sang for city audiences using a 12-bar blues style along with a few traditional and popular numbers. The companies made little effort to seek out good or new talent. They relied on contacting singers who happened to be performing in the New York area or, in many cases, on the singer contacting them.

However, in 1923, too many record companies were chasing too few singers. The more popular singers contracted to one of the Big Three. The lesser-known performers recorded for the smaller companies. For example, Rosa Henderson, Lena Wilson, and Hazel Meyers each appeared on six different labels and Edna Hicks on seven.

Slowly, the major labels began to expand from their New York blues recording base to branch out and look for new artists. Paramount recorded their first sides in Chicago, in 1923, with Ida Cox, Edna Taylor, and New York veteran Monette Moore. These blues sides were interspersed with jazz sides by the Jelly Roll Morton and Ollie Power groups and with New York sessions by Perry Bradford’s Jazz Phools. Paramount continued their Chicago activity with sides by Anna Oliver, Young’s Creole Jazz Band, and the first recordings of the “Mother of the Blues” Ma Rainey. By the end of the year, they added “Wade’s Moulin Rouge Orchestra” and “King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band” to their artist roster.

Okeh, with Ralph Peer at the helm of their 8000 race series, initiated their territorial recording (NOTE: Territorial refers to any recording not made in New York or Chicago) with a journey to Atlanta in 1923, mostly to record white country artists and popular bands like Warner’s Seven Aces and Charlie Fulcher. Possibly as a trial venture, Peer recorded Lucille Bogan and Fannie Mae Goosby, both rural country blues artists. These two sides were issued back to back on Okeh 8079, the first rural black music recorded. Over the following eight years, Okeh made 13 more trips to Atlanta, providing more and more rural blues for their 8000 series race label. They also recorded Mary Bradford and Ada Brown in St. Louis, in 1923, and Sippie Wallace and Peachtree Payne in Chicago. Columbia continued to record in New York City during 1923, making only one trip to Chicago to record King Oliver.

The only other recordings made outside New York City were by the small Gennett Record Company. Gennett decided in 1923 to augment their modest blues and black jazz output by adding recording studios in Richmond, Indiana. While their New York recordings continued to be professional female vocalists, the Richmond recordings drew on artists appearing professionally in Indianapolis, Cincinnati, Louisville, Chicago, and St. Louis, all cities with significant black populations that supported theaters and cabarets where black artists performed.

Gennett was not a big-budget operation that featured “exclusive artists” bound by lucrative recording contracts and the promise of best-selling records with their attendant flowing royalties. Rather, they were a unique operation based on regional artists and regional record sales. Besides the New York artists already mentioned, Gennett recorded Sammie Lewis, Callie Vassar, King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band, Richard M. Jones, Art Landry’s Syncopating Six, the New Orleans Rhythm Kings, and Ferd (Jelly Roll) Morton.

New Orleans black jazzmen recorded for the first time in Los Angeles, in 1922, on the rare Nordskog label featuring singer Ruth Lee. She was accompanied by Spike’s Seven Pods of Pepper, featuring Kid Ory’s trombone, Mutt Carey’s trumpet, and Dink Johnson’s clarinet. Only after New Orleans musicians settled in Chicago and became popular were new recordings sought by musicians and singers still living in the Crescent City.

By 1924, all of the major labels and many of the minor ones featured Race Music as a major part of their output. Some like Paramount and Gennett are remembered today for the extent and quality of their race catalog, many of which remain the rarest and most sought-after 78 rpm record rarities. Both of these labels went out of business, consistent with the stock market crash of 1929 and the resulting Great Depression.

In many cases only a few and, in some cases, a single copy exists of some of the last recordings issued on these and other labels and there are still recordings that we know existed but have not yet been found. Fortunately for us, many of the rarest jazz and blues have been reissued on vinyl and CDs over the years, so we can relive this important part of black history and jazz and blues roots.

Recordially,

Lou Curtiss

Reprinted from the October 2015 issue of the San Diego Troubadour.