Recordially, Lou Curtiss

My Blue Period

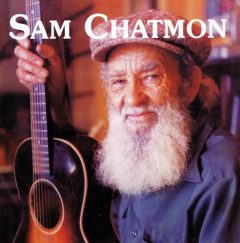

I guess it all started with Sam Chatmon. It was in 1966 and I’d seen quite a bit of blues: Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, Mississippi John Hurt, Son House, Skip James, Gary Davis, Bukka White, and even obscure artists like Willie Thomas and Butch Cage, but that was always as an audience member. I went to concerts and festivals and even worked on a few but never got to know anyone really well. It was different with Sam. Record collector Ken Swerilas had been in Mississippi looking for Bo Carter (Sam’s brother) a few years prior and ran into Sam at his home in Hollendale, Mississippi. He invited Sam out to San Diego and when Sam took him up on it, Ken got a hold of me about finding Sam some places to play. I recommended the Heritage Coffeehouse in Mission Beach and that’s where Sam played when he came here for the first time in 1967. Sam returned to San Diego every year after that to play a little but it wasn’t until he played the San Diego Folk Festival (I think it was the third festival in 1969) that I got to know San well and became the closest thing he had to a manager here on the West Coast. For the next 10 years or so Sam would spend six months of every year here, becoming our own resident Mississippi Bluesman and a living connection to the Golden Age of the Blues in the 1920s and 1930s. He was an original member of the Mississippi Sheiks band with his brothers Lonnie, Bo, Edgar, Harry, family friend Walter Vincent, and others. His half brother, Charlie Patton, called “Father of the Delta Blues,” was a cousin of Charlie and Joe McCoy.

I guess it all started with Sam Chatmon. It was in 1966 and I’d seen quite a bit of blues: Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, Mississippi John Hurt, Son House, Skip James, Gary Davis, Bukka White, and even obscure artists like Willie Thomas and Butch Cage, but that was always as an audience member. I went to concerts and festivals and even worked on a few but never got to know anyone really well. It was different with Sam. Record collector Ken Swerilas had been in Mississippi looking for Bo Carter (Sam’s brother) a few years prior and ran into Sam at his home in Hollendale, Mississippi. He invited Sam out to San Diego and when Sam took him up on it, Ken got a hold of me about finding Sam some places to play. I recommended the Heritage Coffeehouse in Mission Beach and that’s where Sam played when he came here for the first time in 1967. Sam returned to San Diego every year after that to play a little but it wasn’t until he played the San Diego Folk Festival (I think it was the third festival in 1969) that I got to know San well and became the closest thing he had to a manager here on the West Coast. For the next 10 years or so Sam would spend six months of every year here, becoming our own resident Mississippi Bluesman and a living connection to the Golden Age of the Blues in the 1920s and 1930s. He was an original member of the Mississippi Sheiks band with his brothers Lonnie, Bo, Edgar, Harry, family friend Walter Vincent, and others. His half brother, Charlie Patton, called “Father of the Delta Blues,” was a cousin of Charlie and Joe McCoy.

As the lyric writer of the family Sam was responsible for the lyrics to blues standards like “Sittin’ on Top of the World,” “Stop and Listen,” “Corrine Corrina,” and so many others. I learned so much about Mississippi blues from Sam and a lot about living and survival in the rural South. I thought this is as close as I’m going to get.

One day Thomas E. Shaw walked into my store (Folk Arts Rare Records) looking for guitar strings. I’m a record shop and didn’t have any. But I do have an inquiring mind, so I asked him what kind of music he played. It turned out that Shaw was from Brennen, Texas, out in the country near Austin and had originally learned his brand of Texas country blues from Blind Lemon Jefferson (the king of Texas blues in the 1920s). He also played music with a who’s who of old time Texas blues artists, including Willard “Ramblin’” Thomas, J.T. “Funny Paper” Smith, Texas Alexander, and others. As Sam was to Southern Mississippi blues, Shaw was to East Texas blues. And he had been living right here in San Diego since 1934. He ran a series of blues clubs in the late 1930s and 1940s, which he called “after hours joints,” where top West Coast blues artists often played (Little Willie Littlefield, Joe and Jimmy Liggens, Pee Wee Crayton, Smokey Hogg, and others).

Off and on Shaw would get a touch of religion in his life. His daddy was a preacher who wrote songs and performed with the great Texas street singer Blind Willie Johnson, who passed that legacy on to his son. By the time I met Shaw, I already had two or three festivals under my belt and it was sure a major coup to get Thomas E. Shaw, who Blues Unlimited magazine had called the greatest country blues discovery since Mance Lipscomb and Fred MacDowell. And he was right here in San Diego! Shaw, who was willing to draw out the old and early stuff and talk about his childhood in Texas, was the hit of the fourth festival and started a career again that included several fine recordings and a European tour. But that wasn’t the end of it.

Shaw was involved with a group of people who played in the older blues style. When Shaw played his second year at the festival, he brought a friend to play with him. Robert Jefferey was a blues piano man (although he played a pretty mean guitar too) from Oklahoma, who had moved out to San Diego to work as a mechanic for the Marine Corp in the 1940s. He soon became pals with Shaw and played regularly at house parties and blues jam sessions. Bob was the first cousin of blues great T. Bone Walker although his blues style was a lot earlier than T. Bone’s.

Using the contacts I had made in publicizing Sam and Shaw I was able to get the Smithsonian Folk Life Festival in Washington D.C., who were doing a centennial celebration in 1976, to invite Bob to represent San Diego and the state of California at their 13-week festival.

A year after Bob played at our Folk Festival, he put me in touch with Bonnie Jefferson. Bonnie was from Arkansas country or, as she put it, “out in the sticks between Little Rock and Fort Smith.” She was perhaps the most rural of the country blues artists I had run into, doing old songs like “Take Me Back” and “Real Black Mare.” She was also shy and fearful that her welfare money would be cut off if, since it was thought she was making lots of money singing the blues. Often, when I’d get a date for her to play, she’d insist on working under a different name (many times we called her Lu Lewis). We did get her a National Endowment for the Arts grant to buy her a new guitar, but she never did much with it. Bonnie appeared at several festivals as well as concerts at my store and made a handful of recordings (most of them never issued).

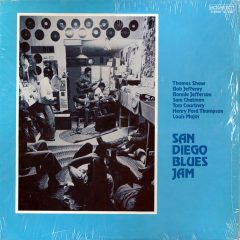

Quite a few people were involved in recording these artists. Chris Strachwitz had recorded Sam long before Ken Swerilas found him. One of the first things I did when Sam came out here was to contact Nick Perls at Yazoo/Blue Goose about recording Sam. An LP on Blue Goose was cut in Ken Swerilas’s living room by John Fahey and myself. With Shaw I contacted Frank Scott to record Shaw playing electric guitar and Nick Perls to record him on acoustic. These LPs appeared on Scott’s Advent Records and Perls’ Blue Goose. I didn’t have as much luck with Bob and Bonnie though. Nick recorded both of them but never released anything. (I wonder now, since Perls’ death, whether his enterprises have been taken over by Richard Nevins and if any of those tapes exist.) He also recorded a second Sam Chatmon album with mandolinist Kenny Hall, which never came out. Frank Scott put out an LP called San Diego Blues Jam (in 1974) that featured Sam Chatmon, Robert Jefferey, Bonnie Jefferson, and Thomas Shaw. It also featured the first recordings of Tomcat Courtney and his then partner Henry Ford Thompson, and West Indian singer guitarist Louis Majors. Shaw also recorded an LP in Holland during his European trip; Sam Chatmon has LPs on Flying Fish, Rounder, Flyright (which includes some live stuff recorded at my store), an Italian label, and a German label that pressed material recorded at his home in Hollendale. Both were LPs.

Sam, Shaw, Bob, and Bonnie got me really involved with the blues and organizing people who play it. In the years since I’ve come to be close friends with Tomcat, whom I have worked with, and booked several other local and national blues acts, but I didn’t become as involved with the personalities of these four remarkable people except for Bonnie (who doesn’t play music anymore). They are all gone. I only wish I knew then what I’ve come to know now. There are so many questions I didn’t ask them (particularly Sam and Shaw). Right now I’m in the process of going through a lot of old tapes of the festivals and concerts I recorded, preparing them for delivery to the Library of Congress and the UCLA Department of Folklore and Ethnomusicology. I’m hearing again and in some cases for the first time these voices singing and playing and talking about musical days and people I only wish I’d been there to see. We were fortunate to have such a vital slice of early Afro-American musical life right here with us in San Diego and I was honored and fortunate to be there right in the middle of things.

THE MEADOWLARK OF THE BORDER

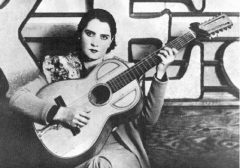

We first brought Lydia Mendoza out to the ninth San Diego Folk Festival in 1975 and she played in San Diego only one time after that (also at one of our festivals). The first time was special though. She had never worked at a college festival before and I had only heard her recordings from the 1930s and was a bit worried about how she would be received.

I shouldn’t have worried, though. As a show biz veteran who knew her music, I was willing to showcase music from the earlier part of her career. She brought down the house, which set the stage for norteño musicians who would become a regular part of the festivals. The second time she performed at the festival she had the “playing music for us gringos” thing down pat. She was a master musician and singer. I was always fascinated by her 12-string guitar playing. Sometimes I’d hear her play a run on the guitar that was awfully close to what I’d hear on a Leadbelly, Willie McTell, or other blues 12-string guitar piece, and I’d wonder about the connection.

We lost Lydia Mendoza in December. I’ll always be grateful that we had the opportunity to see this remarkable performer in her prime. She was an important part of a revival of interest in the older forms of norteño music and an awareness among us gringos that there is another subculture of musical virtuosity in this country. She will be missed.

Recordially,

Lou Curtiss

Reprinted from the February 2008 edition of the San Diego Troubadour.