Tales From The Road

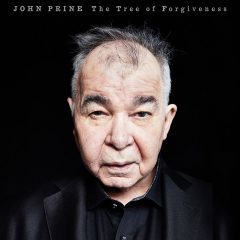

Tree of Forgiveness from John Prine: Old Prines Just Grow Stronger

One of the great mysteries in music today is why John Prine is not a household name in the world at large. His fan base has grown steadily and remained loyal over the last five decades. In his L.A. shows, a favorite pastime is spotting the celebrities in the audience. In the world of Americana country music he is viewed as the influential elder statesman. Even Kasey Musgroves has written a bucket list song titled “Burn One with John Prine.” The most popular country singer-songwriters today know his name and speak it with reverence. They hope to reach his level. He has kept a steady international tour schedule even after facing two bouts with life-threatening cancer.

But, still, the general public has no idea who this great American songwriter is. To answer as succinctly as possible: he is one of the most influential songwriters of his times; he’s part cartoonist in the Jules Feiffer tradition, part storyteller like Mark Twain, and part songwriter with equal parts of Hank Williams and Ernest Tubbs and a dash of Dylan thrown in.

The recent release of his long-awaited album, The Tree of Forgiveness, is a reminder of what has made Prine such a songwriting legend–a songwriter’s songwriter. In a recent interview with The Tennessean, when asked about the theme of the new album, he said, “It’s been pointed out to me that the songs talk about mortality and love and pork chops,” Prine said. “I guess I’m the common thread.” He refers to “Boundless Love,” with the opening lines:

Woke up this morning to a garbage truck

Looks like this ol’ horseshoe’s done run outta luck

If I came home, would you let me in?

Fry me some pork chops and forgive my sin?

On PBS’ Tiny Desk Concert, he said he wrote the songs on a schedule, with meatloaf at a local diner as his lunch break. He xplained that he’d write them in the morning and record them after lunch.

Over the last few years John Prine has been introducing his classic song “Hello in There” with a story of his love for his grandparents when he was a kid. According to him, “I always wanted to grow up to be an old man.” He looks at the audience, gives a wry smile, and says, “Wala, Congratulations!”

At 71 years old, Prine is gradually joining the community of the (old) folks he loves and wrote about with such compassion over 40 years ago, minus the sadness of one of his most famous songs. Prine’s world of aging stands in stark contrast to the one he portrayed in “Hello in There,” a song about the existential despair and alienation of growing old.

However, Prine has grown stronger through his love for a life whose main ingredients are family, friends, and fans and a deeply felt appreciation for his gift as a songwriter after his brushes with mortality. With his wife, Fiona, one step-son and two sons, he’s become an unsuspecting family man who loves meatloaf and pork chops.

Prine’s first release since 2005’s Grammy-winning Fair & Square, The Tree of Forgiveness serves as an apt illustration that the songwriter’s craft is strong as is his creativity, sense of ironic humor and spirit. Today, he’s not so much a lion in winter as he is an old bear coming out of songwriter hibernation. Or, so it seems.

John Prine stands today as one of the pioneers and, some would say, founder of Americana music. Even if that is an overstatement, it’s not flattering to say he is a national treasure. It’s quite an achievement for a much-loved songwriter who has never had a hit song. Not that charted songs are a real measure of greatness of a songwriter’s excellence. Tom Waits, Townes Van Zandt, Eric Andersen, and Guy Clark are evidence of this. However it should be noted that John Prine and Roger Cook wrote a number one country hit for the late Don Williams called “Love Is on a Roll.”

In 1971, when he first arrived on Atlantic records with his eponymous album, he was one among many “new Dylans.” While the vocal resemblance was there, absent was the attempt to be profound or any pretension of an imitation of Bob Dylan. Rather, he came off as a combination of a backwoods country boy with a flair for comedy on the edge of tragedy. Songs like “Sam Stone,” “Paradise,” and “Angel from Montgomery” have become a part of the American songbook. His songs told stories with unique characters and lyrical twists that engaged and gave his audience gems of earthy wisdom. In his sad songs, it seemed there was a subtext of humor beneath the tear. And in his lighter songs, there is an absurdist leaning toward tragedy. He nearly perfects this in his quintessential song, “Lake Marie,” when he says, “We were hoping to save our marriage and perhaps catch a few fish.”

The Tree of Forgiveness contains dark, satiric lyrics set to often bouncy country songs in the vein of his break-the-mold album, 1975’s Common Sense. On the new album’s strongest song, “The Lonesome Friends of Science,” he sings:

The lonesome friends of science say

“The world will end most any day”

Well, if it does, then that’s okay

‘Cause I don’t live here anyway

I live down deep inside my head

Where long ago I made my bed

I get my mail in Tennessee

My wife, my dog and my kids and me

He goes topical on the not-so-cloaked “Caravan of Fools,” as he sends a bleak metaphor in the age of Trump. It is in the grand tradition of “Some Humans Ain’t Human” and “Your Flag Decal Won’t Get You into Heaven Anymore.” His words point to the vibe that’s out in the world of politics today as it plays like a dirge:

Love and devotion

Deep as any ocean

Don’t play by anybody’s rules

With your carousel of horses

And your unforeseen forces

You’re running with the

Caravan of fools

There is something wistful, melancholy and ultimately comforting in the song “Summers End,” which illustrates closure and the changes of the seasons of life. It is purely visual with stream-of-consciousness references:

The moon and stars hang out in bars just talking

I still love that picture of us walking

Just like that old house we thought was haunted

The summer’s end came faster than we wanted.

But, no album by Prine is complete without the unabashedly irreverent song. He’s been able to bring home his absurdist sense of humor as he pokes fun at the sacred cows of religion, death, and divorce on “Jesus: The Missing Years,” “Please Don’t Bury Me,” and “All the Best,” respectively.

The closing song, “When I Get to Heaven” is Prine at his humorous best as his opening lines attest to:

When I get to Heaven

I’m gonna shake God’s hand

Thank him for more blessings

Than one man can stand

Then I’m gonna get a guitar

And start a rock ‘n’ roll band

It is performed with narration to open each verse then his chorus breaks into song

‘Cause then I’m gonna get a cocktail

Vodka and ginger ale

Yeah, I’m gonna smoke a cigarette

That’s nine miles long

I’m gonna kiss that pretty girl

On the tilt a whirl

Yeah, this old man is going to town

He even has some choice lyrics for music critics–present company excepted–as he opens his heavenly club called, that’s right, “Tree of Forgiveness.”

I might even invite a few choice critics

Those syphilitic parasitics

Buy ‘em a pint of Smithwick’s

And smother them with my charm.

And so it goes as Prine finally revisits us with a some fine new songs after 13 years. This album may not stand up to earlier classics like his debut album or The Missing Years, but it does extend Prine’s legacy with the same kind of tragi-comedy twisted together with absurdist insights and illustrations. There are moments of aging wistfulness, but mostly he bucks the aging artist image in favor of remaining true to his craft and creativity. You won’t find anything maudlin here.

Bob Dylan is now famous for his thoughts on John Prine as one of his favorite songwriters in a 2009 interview in the Huffington Post:

Prine’s stuff is pure Proustian existentialism. Midwestern mindtrips to the nth degree. And he writes beautiful songs. I remember when Kris Kristofferson first brought him on the scene. All that stuff about “Sam Stone,” the soldier junky daddy, and “Donald and Lydia,” where people make love from ten miles away. Nobody but Prine could write like that. If I had to pick one song of his, it might be “Lake Marie.”

With each listen, The Tree of Forgiveness resonates with a soft sense of wistfulness and with the joy of one artist’s creative process. It could be said that “they don’t write songs like this anymore” as the cliché goes. But, the truth is no one ever did write songs like this. No one except John Prine.

John Prine comes to the Balboa Theatre on May 19, 8pm.