Tales From The Road

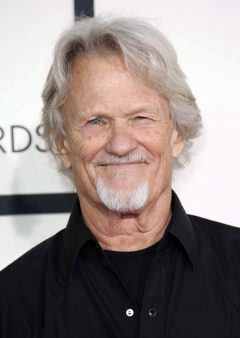

Me and Kris Kristofferson: A 50-Year Cycle of Story, Song, and Heroes

Wide awake and feeling mortal

At this moment in the dream

That old man there in the mirror

And my shaky self-esteem.

–Kris Kristofferson

In the summer of 1970 I was a 15 years-old, a Texas-born-Southern-California-raised kid who lived in a self-built bubble of music, words, and dreams. While my earliest memories are foggy, they consist of the same West Texas terrain that Peter Bogdanovich portrayed in his classic film, The Last Picture Show. Hell, even my memories are in black and white. In my mind’s eye I see the snowy static of our first television; I see the twisted mesquite trees all spikey and red; I see the dusty streets and the cold-as-hell haunted howl of the April winds. I don’t remember it, but I feel it; the night my young father perished in a plane crash in New Mexico. It was April 12, 1956; the western highway called out to my family. Soon enough we were gone. We were headed to Southern California. With little to remember from my one year of life at the time, I can only surmise that I lost a father, who may have become a hero for me.

In 1955, another native Texan found his way to Pomona College in Southern California. His name was Kristoffer Kristofferson. His first name was later shortened to Kris. He was of third generation Swedish descent. After high school along the California coast, he enrolled in college in Pomona. He became a talked-about athlete and an English major. He had his eye on becoming a novelist. He was an odd mix: a jock and a writer, a rugby player and a philosopher. It was a foreshadowing of one of his most famous songs, “The Pilgrim: Chapter 33.” He caught the attention of Sports Illustrated for his prowess in rugby, football, and track and field. He earned a Rhodes Scholarship, which landed him on the British isles at Oxford University. He continued to climb the ladder of success as he developed his love for songwriting, boxing, philosophy, and the writings of William Blake.

After graduating in 1960, Kris would hear the same highway call that my restless Texas family answered in 1957. After five years in military service overseas, Kris was given a plum assignment, teaching English literature at West Point. But, his road pointed in the direction Nashville, Tennessee.

A song and a dream was waiting for Kris Kristofferson.

At the same time, my blended family, the Roland-Hutson tribe, crisscrossed around America, we came to settle in the South Bay town of Manhattan Beach. It was not the town it is today. In 1958 the streets east of the Pacific Coast Highway had barely been paved. I was the youngest child of eight in the chaotic bedlam of a family still living out their Texas culture, complete with a local Southern Baptist church, fiddles, guitars, and Saturday night hoe downs. My stepfather would reel us with his rendition of “Turkey in the Straw.” He loved Ernest Tubbs’ “Walking the Floor Over You.” I absorbed it all. Then, I brought the music I found into my security bubble of music; it was my own world of my imagination with a country western and rock ‘n’ roll soundtrack. I was given a record player that played at only one volume–loud–to the irritation of my teen siblings. For Christmas I got a kid’s version of a typewriter. Music and writing became my world. Even if it meant only typing to the rhythm of the music I heard. By 1963, the Beatles came along, and the world was changed. My brothers and sisters found their way out of the family fold to homes of their own. I stayed home in the music land of my own making.

The road for Kris Kristofferson was one of quiet glory. When Waylon Jennings sang, “You just can’t come from Texas unless you got a lot of soul,” he must’ve been thinking of Kris. Like a Texas Gandhi, a Buddha with a guitar, he went from the offer of a secure job at West Point and a Rhodes Scholar to pushing a broom at Columbia Studios in Nashville. Today he tells of emptying ash trays for the Blonde on Blonde sessions with Bob Dylan. It was there he would hand off tapes to June Carter for Johnny Cash to consider for recording. Cash admitted he probably skipped Kris’ demos across the pond on his property as though they were flat stones. Later, in utter frustration, Kris landed a helicopter on Cash’s lawn to personally give him a cassette of his best songs. Cash finally listened.

Gradually, Kris became a known commodity in Nashville as a songwriter. He held guitar pulls with the likes of Mickey Newbury, Tom T. Hall, Willie Nelson, and Roger Miller. When Miller scored a country hit with “Me and Bobby McGee,” the time was right for the success he had been waiting for. He was signed to record a solo album by Monument Records in Nashville. It became a country landmark album. Today, it could be considered his greatest hits. The year of its release was 1970.

The same year, after more than ten years, my family moved from Manhattan Beach to La Verne, California. The town, formerly Lordsburg, was known for its rich orange groves. Its Sunday church bells echoed another Kris classic, “Sunday Morning Coming Down.” It was also one of the few train stops between San Bernardino and Los Angeles. It was one town away from Pomona College, where Kris had graduated a decade before. It was also a university town with churches, schools, and, to my dismay, no beach or friends. During the summer of ’70, music became my only friend. For me, the previous decade was transformation by music. I always believe those of us born in the 1950s are fortunate to have lived with the best music as our life’s soundtrack. The flow of music went from Elvis and Chuck Berry to the next generation of artists who learned from the icons of the ’50s. The next decade produced artists like Bob Dylan, the Beatles, the Beach Boys, the Rolling Stones, Booker T & the MGs, the Byrds, the Doors, Aretha Franklin, the Mamas and Papas, and Johnny Cash. I absorbed all of it. From 1965 to 1968, while my friends spent afternoons and evenings watching television, I was glued to the radio in my kitchen listening to every song, writing out the lyrics and watching to see where they were positioned on the national charts.

Through my love for Bob Dylan and Johnny Cash, I stumbled onto Kris Kristofferson on a PBS broadcast one summer evening. He was playing solo–just him and his guitar. He sat on a stool. His hair was long, his manner was cool, he looked directly to the camera like he was singing to me. This was not my parent’s country singer. He was not covered in rhinestones. His long strands of hair fell over his face while George Jones sported a crew cut and Conway Twitty carried a pompadour. But, this guy was different–organic–like he’d just come in from hitchhiking on a west Texas highway. On that show, I first heard “Me and Bobby McGee,” “For the Good Times,” Help Me Make It Through the Night,” “Casey’s Last Ride,” and “Pilgrim Chapter 33.” For that moment in my teenage angst, with nothing much to give me hope, there was just me and Kris. The simple stripped-down voice and guitar, the song, his words, his stories, and the characters all came to life. The melody and the words became like a vision of a kind of country music I had never imagined. A kind of country music you could imagine Faulkner, Hemingway, or Steinbeck listening to. Here was a new songwriter that sounded to me like a worthy successor to Hank Williams.

That was my introduction to Kris Kristofferson. I was not alone anymore. I’d found a hero.

Fast forward to a lifetime ahead. It’s 2008. Nearly 40 years has rushed by like the west Texas wind of my childhood. Kristofferson has been out on the road, just him and the guitar. It was like he had just rolled in to town looking for a gig. He returned to Doug Weston’s Troubadour where he held his first L.A. show. Over the near-40 years, he had become one of America’s finest living songwriters. He had recorded a legacy of songs and albums. He traveled for years with one of the best bands in country music, the Border Lords. He became a well-known actor, a movie star, an activist, and a country music elder statesman with honors, awards, and tributes. He was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame.

In that year, I was still living in the bubble of music and words, but having also ventured out into the world. I had lived enough to know the truth behind the heartbreak in many of Kris’ songs. I was divorced, living with my son in an apartment in San Dimas, California, next door to La Verne. I would sit for hours in the darkness of my living room with only the glow of my computer monitor. It was there I saw an announcement: Kris Kristofferson was to play a solo show in Glendora. It was a 15-minute drive away. It would be on the following day, a Sunday. It was a matinee. For an artist I had seen at much larger venues with bands, friends like the Highwaymen, it seemed that a Sunday matinee was strangely anti-climactic.

There are moments when life’s twists and turns can get you down. It’s a time when, as Kris has written, heroes happen when you need them. For two hours on that autumn day in 2008, a hero happened because I needed him. Kristofferson. He stood on the stage, tall and strong, and he gently strummed his songs, singing through every era of his recording career. He told no stories except for those heard in those classic songs. For all too brief of a time I listened to the tale of obsession in “Darby’s Castle,” I heard “The Pilgrim: Chapter 33,” the tribute he wrote to friends like Jack Elliot and Dennis Hopper, which could have just as well been about the man himself as “a walking contradiction, partly truth and partly fiction.” I heard the song about two Okie children during the Great Depression as they stepped out of the pages of Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath. Then came “The Silver Tongued Devil” and “Bobby McGee.” His final song included the refrain, “go break a heart.” As he walked off the stage, I knew I had rediscovered my old hero. He left the gig for another American highway to another audience waiting to hear him again.

Today, Kris continues to record, sometimes re-recordings with old and new friends, as he did with the recent Cedar Creek Sessions. He also released an album of new material in 2013, Feeling Mortal. For me, most of my family are now scattered across America or now reside in heaven. I have learned to leave my bubble all together and instead I reach out to the world around me to share the music and words of life through music of every kind. I learned to do this from Kris and others like him. No matter what fear invades, it is better to let my voice be heard rather than hide in a bubble of security. Kris and me. It’s been a long highway. There are still miles to go. But, each day is a gift, always with one more song to share in the shadow of the legacy of my memories of Kris Kristofferson.

God almighty here I am

Am I where I ought to be?

I’ve begun to soon descend

Like the sun into the sea.

–Kris Kristofferson

Kris Kristofferson comes to the Belly Up on Monday, January 15 at 8pm, 143 S. Cedros in Solana Beach.