Yesterday And Today

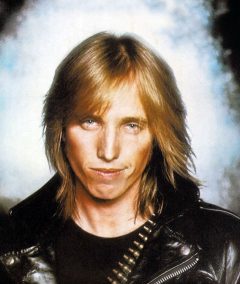

Tom Petty: A Fever Dream Come True

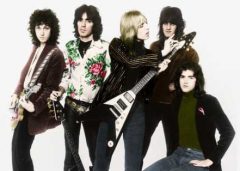

Tom Petty & the Heartbreakers, circa ’77: lead guitarist Mike Campbell, bassist Ron Blair, Tom Petty, drummer Stan Lynch, and keyboardist Benmont Tench.

It’s October 20th, 2017, and it seems insane and cosmically cruel that Tom Petty is not around celebrating his 67th birthday with his family and friends. That tragic fact brings tears to my eyes. More than likely it has a similar effect on you.

It’s a mathematical inevitability that our cultural heroes born in the zone of the Baby Boom (1946—1964) are going to start leaving their bodies en masse. But the last couple of years have been a harsh reminder that the golden age of rock ‘n’ roll is morphing into a mass apocalypse; I’ll spare you the roll call. Call it post-modern mortality, but this particular passenger train isn’t stopping for anything or anybody, and if the times that we are a-livin’ through isn’t a reminder to enjoy every sandwich, well then I don’t know what is.

Down-to-earth, unencumbered by pretension, poetic and minimally direct at the same time, Tom Petty, both with and without his band of musical empaths, the Heartbreakers, is an institution: one of the best representations of what is most admirable within American art and culture. And it’s easy to take our institutions for granted. Hell, some of them, like the IRS or McDonalds, could disappear and our lives would be infinitely better for it. Other institutions, though, seem like they’ve always been a part of our lives. And when one of them up and disappears without warning on a miserable Monday morning, the void that is left in its wake is capable of setting off the deepest emotional reverberations. At least that’s how it felt to me when the news started circulating on October 2nd that Petty had suffered cardiac arrest at his Malibu home; finally passing over to the other side at 8:40 p.m. in Santa Monica, California at the UCLA Medical Center at the age of 66. He had just performed to a sold-out crowd at the Hollywood Bowl seven nights earlier. How was this possible?

Tom Petty’s appeal is rooted in his ability to masterfully bridge the gap between his own trials and triumphs in order to make great art for the masses. He wrote the quintessential pop single over and over again, somehow baring his soul in a manner that shares the personal in a way that is profoundly universal. You feel like he’s singing to you, for you, through you–as if he’s articulating some ancient truth that everybody knows and can relate to, while always making it his own, in that nasal drawl for y’all.

There are very few things in life that are as pure and simple or constant, and to know the music of Tom Petty is to understand the true essence of what it is to be alive. You can set your compass by him and know that you’re on the right course across the stormy seas of life’s uncertainty. He’s the North Star of rock ‘n’ roll, which is sort of ironic since he hails from the south.

*****************

Thomas Earl Petty was born and raised in Gainesville, Florida, coming of age at a time in the 1960s when long hair and rock ‘n’ roll were frowned upon by most of his contemporaries in the southern United States. In other words, if you looked and sounded like a West Coast hippie, you were bound to be called “faggot” and get your ass kicked by the asinine. But Petty learned early on how to transcend the locale limitations of being a redneck through the magic of radio, the power of music, and the transformation that can occur when you understand how significant the sound of three chords is in the face of all the other soul-wrenching alternatives. In short: rock ‘n’ roll music as a means to deliverance. Most importantly, he had the ability to dream big, turning the everglades of Hicksville into the grander expanse of Dreamville. He’s an example we could all take a few lessons from.

If you want to know what makes Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers tick, the best place to investigate, besides the recordings themselves, is the epic four-hour 2007 documentary Runnin’ Down a Dream by Peter Bogdanovich. Produced in tandem with the band’s 30th anniversary, it serves as an excellent primer for the uninitiated as well as providing sacred manna for the hard-core. For those who like succinct soundbytes and suffer from short attention span syndrome, pass this baby over. Because this is a band whose history runs as deep as a Georgia well on the family farm’s back 40, and it’s a story that just can’t be told in 15 or 20 minutes. Not even the conventional format of two hours does it justice. This is the John Ford of rock documentaries and is required viewing for anyone who has ever been inflamed by the liberating muse (and fuse) of high-octane rock ‘n’ roll.

With the full support and comradeship of the Heartbreakers–lead guitarist Mike Campbell, keyboardist Benmont Tench, bassist Ron Blair, and drummer Stan Lynch–Petty’s biography has the classic hallmarks of The Hero’s Journey by Joseph Campbell. Hometown boy becomes obsessed with Elvis Presley and the British Invasion, buys a guitar, dreams of glory and getting the hell out of Dodge, and miraculously breaks through to a worldwide audience on the strength of one of the greatest song catalogs ever composed. A local following with his band Mudcrutch inspires visions of grandeur, and damn it if the dream didn’t just come true–it exceeded his wildest imaginings. He managed to retain the core lineup of his band for 40 years while still suffering one or two intraband squabbles and a drug-induced fatality. He moved over 80 million units worldwide, with multi-platinum albums, sold-out tours, accolades, and being accepted as a peer among his legendary childhood idols. Could it possibly get any headier than having 15,000 fans sing the lyrics of your songs back at you in unison, with Bic lighters held aloft? I sincerely doubt that it does.

But anything that’s worthwhile rarely comes easily, does it? With a tenacious temperament that served him well in so many ways, there was a downside to his anger issues, like smashing his fist into a wall out of frustration and pulverizing every bone in his hand, petrified he’d never play the guitar again. There were legal battles with record companies who wanted to fleece his fan base, endless afternoons spent with lawyers, and the arsonist who set fire to his Malibu house while his family was inside asleep. Petty somehow embodied and rose above it all: marriage, children, divorce, reconciliation and retribution, and the redemption of finding a life partner who ended up saving his life.

But after all the tobacco and refer smoke clears the room, what you really want to do is get a hold of all of Petty’s LPs (preferably on vinyl, natch) and play ‘em until the grooves disintegrate. If CDs are good for anything, they are a convenient way to spin tunes in the car, and TP’s catalog is a soundtrack for the open road: on the move, with the horizon constantly shifting. I mean, isn’t that why he named his 2006 LP Highway Companion?

In the official program for their True Confessions tour (Alone + Together), Bob Dylan says: “I’ve got a lot of respect for Tom–he’s a deep and soulful cat. Tom is a heroic character in his own kind of way. He’s dedicated. But musically speaking, he’s gutbucket. And he’s got a very good band; they’re quick and they know the fundamental music.”

It’s all about creating an emotional connection, with yourself as well as your audience. In 1999, as Petty was promoting his latest LP Echo on the Charlie Rose Show, he had this to say regarding his attraction to the Chicago blues of Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf: “The purity [is what I love]. There are very few lyrics, but they say so much to me. There are great metaphors in the lyrics. It’s very pure: there are no toxins involved. It clears my head when I hear it. The best music does that for you. So much of this music is about feel. Technique is great, but it will never substitute for feel. What the Heartbreakers and I are striving for is feel: so that you feel it and you believe it. My singing voice compared to Pavarotti wouldn’t stand up. But I think I’m good at getting over a believability. If I’m going to play the narrator, I want people to believe me. And I think those are the best singers, the ones you tend to believe.”

*************

Talk about learning life lessons from a rock star. In a 1978 Circus magazine article Petty related how as a child his mother always taught him to leave a little edge to his hunger when he left the dinner table. It’s sound advice–it keeps the twin dogs of gluttony and greed at bay and reinforces a sense of trust that there will always be another meal waiting for you at the next rest stop. Insecurity and inherent selfishness cause people to scarf down more than they need of anything, be it food, material possessions, money, or power. Imagine learning a vital life lesson from a rock ‘n’ roll singer these days? In today’s culture, that seems impossible. But not when Tom Petty first came around to spread the news of what it is like to be joyously alive and wail about it in all its confident, confused, battered, and bruised glory. That’s what I hear when I put on a Tom Petty record, and it is what I witnessed every time I saw him walk on stage, where the ritual of playing in a rock ‘n’ roll band was as much a church and a release for TP and the HBs as anything. Rock ‘n’ roll can be a shrine, a savior, and a reason for living: imparting meaning upon what for so many can cease to mean anything. You can become so numb by the cruelness of human nature that you can forget how beautiful it is to exist and how fucking great it is to be alive. When I saw Tom Petty on stage, whether a mile off in the distance or from five feet away, he served as a mirror of extreme intelligence, beauty, compassion, and PASSION–he might be beatific or full of sorrow or just downright pissed off–he was all those things and so much more. Like all the great artists of antiquity, you can project whatever you want or whatever you need upon them and feel that they are an extension of YOU, and what needs to be articulated in that exact moment. Remember, audiences don’t come to a show to see the performer–they come to see a reflection of themselves. When you bought a ticket to hear Tom Petty sing his universal anthems of teenage love and lust and the pain of separation and the glow of connection and the weariness of growing older and the arduous task of lessons hard fought and won, you felt like he was expressing something deep within yourself. And that’s just one of the thousands of reasons why 15,000 people came out night after night to see those archetypal aspects of existence reflected back to them. It certainly wasn’t for the $15 beers and $50 t-shirts that were being sold at the concession stand, even if $50 is a small price to pay for the reminder years from now that you were there and were a part of a moment that won’t ever come around again. Life is short, life is fleeting, and life is full of joy and sadness. So grab your golden ticket, and be thankful for today, and don’t look back in anger, because the chance to live life to the hilt is right here. You hear in the shout of “Refugee,” and the yowling screams of “Century City,” and the toil of knowing that life can often be difficult, but you persevere anyway. For most of us, there is no other option. So we grit our teeth and get on with the business at hand. And after the day is well spent, and the satisfactions well earned, we celebrate our victories and are grateful that the hardships weren’t more numerous in the final tally.

It seems like everyone has a Tom Petty story (or three) to share, and in that regard I’m just like anyone else in the extreme expanse of popular music. The first time I laid eyes on him was in the movie FM from April of 1978, smoking an ubiquitous cigarette, being interviewed by actress Cassie Yates. “Breakdown” and “American Girl” were receiving a fair amount of airplay in the DC area where I grew up, and by the time You’re Gonna Get It! came out in May of ’78, I was madly hooked on the timbre of his voice, the chiming Rickenbackers, and the Hammond B3 organ supplying the bedrock of his sound. I listened to him talk about Damn the Toropedoes on Jim Ladd’s Innerview radio program in 1980. And I read with glee in Rolling Stone how he fought MCA Records when they tried to raise the price of LPs across the board by a dollar when he came out with Hard Promises in 1981.

The first time I saw TP and the HBs in concert was in 1983 on the Long After Dark tour when they headlined the 91X-sponsored X-Fest here in San Diego at what was then-called Jack Murphy Stadium, with an incredible lineup that included the Flirts, Modern English, Bow Wow Wow, the Stray Cats, and the Ramones. Tickets were only $14.50 for six bands! At the time I was disappointed that I didn’t get to see original bassist Ron Blair perform, but in his place was the remarkable Howie Epstein, and they sounded as great as any other band that I have ever seen. This would be true all 14 times that I witnessed Tom Petty in concert–when TP and the HBs were on stage they were always the best band you ever heard in your life, bar none.

There has been a lot of political correctness bandied about as of late regarding the confederate flag and what it supposedly symbolizes. But the fact remains that the attitudes and culture of the traditional south (“rebels”) are far more complex than the Gone with the Wind over-simplifications that our current crop of revisionists assert. A lot of that ambiguity and mixed bag of emotions can be found on the Southern Accents LP from 1985, which was an attempt by Petty to expand the parameters of what he was creating beyond the successful formula that had developed over the first five LPs. The Southern Accents tour was a departure of sorts, with a horn section adding additional texture to the mix. There is an excellent time capsule of Petty driving around with a crew from MTV, reminiscing about his old hometown, cruising by WGGG-AM (“Watch Gainesville Grow Greater”), the Top 40 station that he grew up listening to as a teenager in the ’60s.“Right in the middle of Gainesville is the University of Florida. Ever since I was about 15 we’d make a living off of these fraternity parties, and we learned a lot from the college students–they were still a little bit weird. I remember nearly being beaten up one night for wearing a shirt made out of the flag at one of these fraternity parties. I think it was Don Felder, a local guy who later became an Eagle, who saved me from that particular fight. Felder was playing next door–I think he got beaten rather badly and suffered some minor brain damage.

“What probably ruined school for me is when I got a guitar and got in a band. It was never intentional–I mean maybe there was a bit of rebellion, but you’re never aware of it until you have somebody wagging their finger at you. But remember to get your education, because if you can’t get a job, you can at least talk a lot.”

Petty’s first band, Mudcrutch, cut an independent single in 1973 titled “Up in Mississippi Tonight,” and it’s an odd synchronicity that on Petty’s 27th birthday his fellow Gainesville, Florida contemporaries Lynyrd Skynyrd went down in a plane crash near McComb, Mississippi.

**************

In 1986, TP and the HBs backed up Bob Dylan for what was supposed to be a one-off performance at the first Farm Aid concert in Champaign, Illinois, and it turned into a two-year adventure–the first leg of what became Dylan’s Never Ending Tour. I saw four of those performances; they were a match made in musical heaven, with Dylan having the greatest backing band of his career, on par with the Hawks 20 years earlier in 1966.

But after awhile, doing double duty began to take it’s toll, as Petty told Sylvie Simmons in Mojo in 2006: “I just thought, okay, it’s time to get off this bus now and get back to being us. I think I thought we could do both, but we couldn’t, it was wearing me out. And then I wound up in a band with him again.” Of course, that band ended up being the Traveling Wilburys, a spontaneous supergroup that fell together when George Harrison needed a b-side for one of his singles. When the spur of the moment “Handle with Care” was deemed “too good” by Warner Bros. Records, an album was swiftly created, selling millions in the process. Together with Dylan (Lucky Wilbury), Harrison (Nelson Wilbury), Jeff Lynne of ELO (Otis Wilbury), and Roy Orbison (Lefty Wilbury), Petty became Charlie T. Wilbury Jr. and a band with five singer/songwriter/guitarists turned into an unexpected sensation.

It’s a pity that the Wilburys never went out on the road, particularly as Roy Orbison died two months after the Traveling Wilburys Vol. 1 came out. But I did get to see three-fifths of the Wilburys take the stage at Madison Square Garden on October 16, 1992 to sing “My Back Pages” for the 30th Anniversary Concert Celebration honoring the career of Bob Dylan. Petty and the Heartbreakers did great versions of “License to Kill” and “Rainy Day Women #12 & 35,” but the real highlight of the show was seeing George Harrison perform “If Not For You” and “Absolutely Sweet Marie.” Along with Stevie Wonder, Johnny and June Carter Cash, Neil Young, Eric Clapton, and Lou Reed, it was a very special evening. Amazingly, there were even better shows to come.

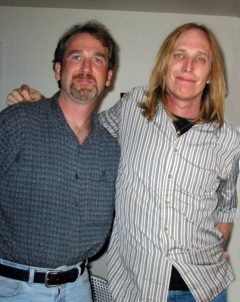

I explained in the online version of my Steely Dan article from the October edition of the Troubadour how one of the roles of working at Reelin’ in the Years Productions was acting as a consultant for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, which took David Peck and myself to the Waldorf-Astoria ballroom in New York City for five straight years to witness the induction ceremonies in person. In 2004, we had the privilege of seeing Petty and Jeff Lynne induct George Harrison as a solo artist, which included the spine-tingling jam at the end of the evening with Prince soaring through an electrifying “While My Guitar Gently Weeps.” In 2002, we were in attendance to see Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers get inducted into the Hall, affording us the opportunity to meet Petty and Mike Campbell and develop a professional relationship. Several months later we ended up hanging out for an hour with the band backstage at the San Diego Open Air Theatre and this is how I found out firsthand that Tom Petty is an absolute bad-ass of a sweetheart, and as much a fan of rock ‘n’ roll as anyone in the universe. Sometimes you meet your heroes and they turn out to be jerks or in a bad mood on that particular day. Tom Petty, and all of the Heartbreakers, could not be any cooler. (The picture with Tom was taken October 29, 2002, and a month later, to the day, TP and the HBs were at the Royal Albert Hall in London performing at the Concert for George, and thanks to the generosity of Mike Campbell, I was able to sit four rows from the stage. That was the best concert EVER, and for a full recap of that once-in-a-lifetime evening, check out chapter two in my book Encyclopedia Walking: Pop Culture & the Alchemy of Rock ‘n’ Roll. The DVD of the event fills in the remainder of the story. Hallelujah and Hare Krishna.)

There is something about Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers’ music that has kept the sacred fire of what was special about rock ‘n’ roll in the first place burning bright through the long, slow darkness that has enveloped the entertainment industry over the past four decades. You have to go back to a time before the advent of MTV and segmented radio programming to understand what I’m talking about, and that is largely what the song and much of the 2002 LP The Last DJ is all about.

In the companion DVD, The Last DJ Sessions, Petty has this to say about the album and the state of the music business: “It looks back at a time when pop radio was all on one station. The disc jockeys that played the records were actually personalities–they were people that you got to know. And some of them you loved and some you just hated. They also played a role in selecting what they played–it wasn’t just a playlist. I think it was a little more interesting. You had corporations take over radio chains and radio stations and you have guys that come in and companies that program the station by research and it’s very cold.” This sounds exactly like the plot to the aforementioned FM film.

In the song “Joe,” Petty sings about how shallow and callous the music business has become: “We could move catalog if he’d only die quicker–send my regards to the gig and a case of good liquor.”

“It’s really an odd job to be in a rock ‘n’ roll band sometimes, especially when you’re 51 [sic] and you’re still in the same rock ‘n’ band that you were in when you were 24, or younger really. When I think about it, I’ve played with Mike Campbell and Benmont Tench since I was 18 or 19. We know each other really well. I’m in the same band because I’ve never heard another one that I wanted to join, that I thought was a better band for me.

“Writing is really a hard thing because sometimes you get so close but you didn’t get there, and so you discard that and move on. And sometimes it happens really easily and it’s kind of a mystical,

magical thing.

“You don’t see many new acts with a continuity to it–there’s usually not that second hit record. And that’s because these acts aren’t nurtured in any way by the people that hired them. We were very nurtured along at the beginning, and sort of taught the artistry of the recording studio and how it’s a very different animal than the stage, and we learned how to hear something in our head and make it happen. But I don’t think they get that education much these days, and the result is that if you’re only going to deal with the latest, newest thing, then something new has got to be happening all the time. And unfortunately, that has never been the case in pop music. So a lot of drivel is forced on us just because of that fact–they’re looking for something new, rather than an act that just had a record out and did really well, and maybe it’s possible that they might make another one. I think they’ve even got the audience in a place where they give up on that–they don’t expect much.

“I made records 25 years ago that I still hear on the radio. I use the music business a bit, but the album is a pretty good metaphor for everything else that’s going on in America at the moment, and indeed the world. And it deals a little bit with the celebration of mediocrity in the media.

“I still enjoy hearing it [The Last DJ] even as much as I lived with it, and that was the case with things like Wildflowers, Damn the Torpedoes, or Full Moon Fever. Those were things I played a lot at home. But after you’re gone all you leave behind is that music–so it’s really worth spending a little time and getting it right. Those things are forever.”

*****************

In terms of the recording studio, the band that began and ended Petty’s musical journey is Mudcrutch, and the complex web that they weave throughout Petty’s career is expressed in great detail in Runnin’ Down a Dream. As Petty reminisced for Bogdanovich’s camera he stated, “I felt like we had left some music back there, and I wanted to go back and get it.”

Mudcrutch broke up in 1975, after Petty was offered a solo deal by Shelter Records, and in 2007 he decided to reform the group and explore what they sounded like after a 30-year hiatus. Three-fifths of Mudcrutch is Petty, Campbell, and Tench, along with guitarist Tom Leadon and drummer Randall Marsh. In Mudcrutch, Petty is the bassist and shares lead vocal duties with Tench and Leadon. They performed a week-long residency at the Troubadour in West L.A. in April/May of 2008, and I was able to catch the last two performances from the lip of the stage. The POV was absolutely mind-boggling, with Petty telling the audience, “This is probably the finest bar band you’re gonna hear in West Hollywood tonight.” Or any night for that matter.

Mudcrutch was far from a one-off lark, and the band reunited again in 2016 for a second LP titled 2. It would turn out to be the last LP released in Petty’s lifetime.

****************

Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers spent 2017 touring the United States, Canada, and London, celebrating their 40th anniversary by performing 53 gigs across five months, including the KaaBoo Festival in Del Mar and culminating in a three-night stay at the Hollywood Bowl in September. “This has been a wonderful year for us,” he told Randy Lewis of the Los Angeles Times, in what would be his final interview. “This has been that big slap on the back that we never got.

“The thing about the Heartbreakers is, it’s still holy to me. If that were to go away I don’t think I would be interested in it, and I don’t think they would [either].”

As Petty told Martyn Atkins in 1994: “If you’re a young band and you have a choice about whether you’re going to do this or not, you’re in the wrong business. I never had a choice–I would do this anyway–and do it if no one liked it. It’s way romantic to read these things about perseverance, and I suppose I am stubborn and tend to persevere, but really, the truth is I have no choice, because I would have done it anyway. It’s just what I do. I think it’s the same for most people who are around that long. You would have done it anyway. We’d still be trying to get together and play some music.”