Yesterday And Today

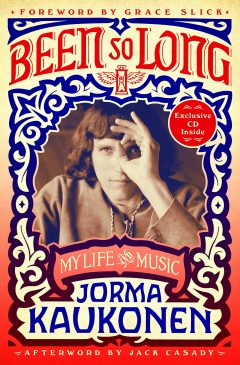

Jorma Kaukonen–Been So Long: My Life and Music

There’s an old saying that goes “If you can remember the Sixties, you weren’t there.” Those 60 and over go ha-ha, ho-ho, I get it; too many flashbacks, too many bong hits, far too many uppers to balance all those downers, and too many long drum solos. The conceit was that there was too much experience crammed into too-few years; many of us who thrived and jived on the wide, permissive mores of the Sixties ought to still be overwhelmed, asking ourselves what happened. Who among us might recollect that glorious experiment in living? Jorma Kaukonen, founding member of and lead guitarist for the definitive ’60s/San Francisco band Jefferson Airplane, remembers, and brings his recollections together in a new memoir Been So Long: My Life and Music. It’s worth noting up front that the musician, a stalwart figure who preferred to remain in the background, was quiet though attentive while fellow JA members Grace Slick and Paul Kanter did the many media interviews. He admits early on that the book is comprised of memories about how events transpired, but that some of what he’s recounting might be vague or incomplete in the telling. He offers a disclaimer in the introduction, mentioning his imperfect recollection: “…this is my story as I remember it as seen through the prism of my mind’s eye. I can do no better than that.”

However reticent Kaukonen was to speak with the press at the peak of his fame with the Airplane (and later with Hot Tuna, his long-term folk and electric blues project with JA bassist Jack Casady), the author’s memory seems to serve him well within these pages. A second-generation American of Finnish descent, he was born in Washington DC in 1940. The young Kaukonen had already seen much of the world, particularly the Philippines and Pakistan, courtesy of his father’s diplomatic corps assignments. His early years seemed a case of accidental wanderlust, his family moving city to city, country to country, with Kaukonen easily making friends in each new home through, it seems, shared interests in music, cars (“gearheads” as they called themselves) and, to be sure, girls. While in Washington he acquired a guitar and began learning traditional folk songs, learned the advantages of keeping his guitar tuned, and made a lifelong friendship with future JA bassist Jack Casady. What Kaukonen realized was that playing music was pretty much what he wanted to do and muses that music seemed the elixir that brought a new dimension to his life than merely existing and putting up with boring jobs and mean people. Laconically and tersely, he concludes “music seemed to me to be the reward for being alive.”

The first half of the book is full of memories about his family, his two sets of grandparents from Europe who were searching for opportunities that migration to America promised. He speaks lovingly of his parents, aunts, and uncles and shares what he recalls of their expectations for a new life in the promised land. Most tellingly, though, was Kaukonen’s seemingly slow but eventual immersion into music. We see it in negotiation with his father for a guitar, his playing DC clubs with Casady, and using fake IDs when Casady was playing lead guitar and Kaukonen played rhythm. And we see his growing interest in folk music styles that would become the defining essence of what would become his electric guitar style with Jefferson Airplane. Developing into a fine finger picker and with an affinity for the simple and elegantly articulated patterns of folk-blues, Kaukonen incorporated these techniques into his eventual electric work for the Airplane, giving them a rattling guitar sound unique in an era where every other guitarists fashioned Clapton impersonations. Kaukonen’s style slid and slithered, his leads full of peculiar tunings, odd emphasis on blues bends, and a jarring vibrato that made teeth chatter and nerve endings fire up. It was a style that informed the Airplane’s best songs “Lather,” “White Rabbit,” “Greasy Heart,” and which was a sound that was an essential part of the complex and wonderful weave that characterized this band’s best albums, from Jefferson Airplane Takes Off through Volunteers.

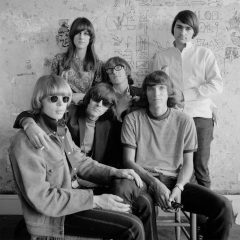

At a point, Jefferson Airplane were among the top bands of the era, in fact one of the top bands in the world, originating within the counter cultural environs of San Francisco and adventuring beyond those city blocks to perform historic rock gigs such as the Monterey Pop Festival and Woodstock. It was something of a charmed life and Kaukonen was earning a good amount of money. Admittedly, he was willing to start spending it, i.e., buying homes, new cars, new equipment. The band was at the top of their game, and on a Dick Cavett Show following the last night of the Woodstock Art and Music Festival, myriad performers, including David Crosby, Joni Mitchell, the Airplane, and Steve Stills, sat around a rather casual set for the program and bantered breathlessly about the monumental experience they’d all just been through. In the afterglow, at that moment, it seemed as though Ralph Gleason’s mid-Sixties prediction in Rolling Stone that the Sixties youth, spearheaded by the music, musicians, troubadours, and poets of the time, would change America profoundly by enacting a revolution without bloodshed or bombs. The music would set you free. Believe me, I was there, watching the Cavett Show on my parent’s basement television as well as reading the newspaper and 6pm news reports on the massive event. For a few minutes, just a few, it all seemed possible, especially when watching the beautiful and brilliant Grace Slick and the Teutonically authoritative Paul Kanter lay it out for what many took to be a forecast of the American future. Kaukonen was on the set as well, in the background, sitting with his guitar. He was happy to let Slick and Kanter do the talking; as he reiterates through the narrative that he was happy to play his guitar and let others be the prophets.

There is much ground Kaukonen tries to cover in Been So Long, but there is a lack of urgency on the author’s part to offer detail, specifics, characteristics, or insights connected to the material progression of his story. He is an able writer who conveys a personality that’s sufficiently humble after the long, strange trip he’s been on. He is grateful for the gift that has been bestowed upon him and humble in the face of the hard times and devilries he’s survived. But there is a kind of cracker barrel philosophy in tone, succession of incidents, occasions, fetes, celebrations, and disappointments in his life, told in sketchy detail summarized with a cornball summation, a reworked cliché, a platitude passing as hindsight. He mentions family, wives, children, famous musicians in a continual flow of circumstances, but does not actually say much beyond the convenient sentiment when you expect him to give a hard-won perspective of his adventures before and after the rock ‘n’ roll life. You’d assume it would be impossible to be dull telling a story of a life as jam-packed as his, and yet Kaukonen seems intent on doing just that.

He does not tell tales out of school, he doesn’t reveal the quirks of his friends, what he might consider the essence of their genius. Structurally, the book reads as if it were compiled from note cards and handwritten journals, arranged in order (more or less), assembled for a rapid walk-through rather a revelation of what drew an artistic temperament to this kind of life at all. Kaukonen’s reticence to write more deeply prevents a fascinating and unique tale on the face of it from being more compelling. It’s as if he’s talking about things he would rather not disclose; the half-measured commitment shows up when he mentions his increasing reliance upon and addiction to alcohol throughout the chapters. Using phrases from the principal writings of Alcoholics Anonymous and peppering his prose with 12-step mottos and clichés, it’s apparent from those in recovery where the musician got help for his alcoholism. A large part of the A.A. program is for members to find a God of their understanding, a power greater than oneself, which can help them with their problem. For those who have a “God Problem,” the fellowship also refers generically to “a power greater than oneself.” A god of one’s own understanding? Fair enough, but Kaukonen here takes to writing God as “G-d” for reasons that remain explained. It’s one thing to not demand that others have the same theology as yourself, but it’s another to routinely omit an offending “o” when the world God comes into expressive play. Being more forthcoming on this quirk, offering a reason for the eccentric use, would have illuminated Kaukonen’s story to better, more vivid effect. It is a small mystery, an annoying one, a recurring bump in the road that stops the reader–what is Kaukonen not telling us? Elaboration does not come.

Perhaps an as-told-to memoir like Keith Richards’ Life would have eased more nuance and insight and crucial detail from the hesitant Kaukonen. Richards, speaking at length and on-the-record with collaborator James Fox, the Rolling Stones guitarist speaks frankly and at length about the highlights and low spots of his life in music. Free to speak as he pleased to Fox’s probing questions and not having to worry about censoring himself while at the typewriter or with pen -in-hand, Life is a witty, harrowing, bristling account of one remarkable musician’s life. On the surface, Kaukonen’s tale is as full and intriguing as a rock ‘n’ roll biography requires–worldly as a young man, ROTC, a lover of music and cars, a founding member of one of the most significant bands of the Sixties in the midst of a major cultural revolution, drugs, money, fame, glory, flaming out, regrouping–the outline is here, yet Kaukonen does little to flesh it out or reveal the sex, sizzle, and drama under the facts and their note-card descriptions. Richards’ work with a collaborator allowed his mouth to run if it needed to tell the best story he had, his own, the final payoff being an engrossing read blessed with Richards’ hard-won and refreshingly off-hand wisdom. The Jefferson Airplane guitarist is not so garrulous and is reflectively taciturn and terse, in fact. One needs to respect his right to tell his story as he sees appropriate; the shame is that what is likely a great story doesn’t so much get told as it gets mentioned in passing. Been So Long remains a fascinating read and is an interesting addition of firsthand accounts of the psychedelic revolution in the ’60s from a key player. The irony is that Kaukonen does remember the decade–he just doesn’t see the need to get into the weeds, dig in the dirt and relate something fuller, an account of a life fully lived. The author’s general view is that his was a life worth living. What is unfortunate is his reluctance to examine more closely.

Regardless of whether you like the book,, his music is still superb. Jorma Kaukonen will be coming to AMSD Concerts on March 1 for a solo concert. AMSD Concerts is now located at Sweetwater Community Church, 5305 Sweetwater Rd., Bonita.