Recordially, Lou Curtiss

Evolution of a Song

I’m always curious about how songs evolve, and I guess there’s no better documentation of that than by listening to recordings. Take Hank Williams’ “Lovesick Blues,” which most of us consider a country music standard. Recorded by Hank in December of 1948, it had been a country song when cowboy crooner Rex Griffin recorded it in September of 1938. However, when medicine show blackface songster Emmett Miller recorded it back in June of 1928, he used backup by his Georgia Crackers, which included jazzmen Leo McConville on trumpet, Tommy Dorsey on trombone, Jimmy Dorsey on clarinet, Eddie Lang on guitar, Arthur Schutt on piano, and Stan King on drums. This was a jazz-blues-minstrel hybrid that was anything but country.

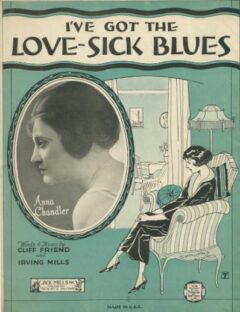

It was obvious that both Hank and Rex had heard Emmett Miller’s recording. There are enough similarities in the way the song is sung to make that absolutely certain. The same blue yodels are in the same place So, where did Emmett Miller get the song? The answer is in a fourth recording made in 1922 by vaudeville song-and-dance man Jack Shea. All the words are there but the tune is a bit different and there is an additional verse about going to the doctor:

He looked at me and said, “Why, your final lowka towka is badly bent” . . . you’ve got the lovesick blues.

The record by Jack Shea lists Cliff Friend as single author of the song. All the later versions list Irving Mills and Cliff Friend as authors. Irving Mills was a very successful arranger, agent, friend, and sometimes singer with bands like Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway, Don Redmon, the Mills Blue Rhythm Band, and his own Hotsy Totsy Boys (a.k.a. Mills Musical Clowns and Mills Merry Makers). My guess is that he got the musicians together to back up Emmett Miller and, as a result, took a piece of the action on his songs. “Lovesick Blues” made him a good piece of change over the years. As for Cliff Friend, who was a prolific songwriter from the early ’20s into the ’50s, with songs like “June Night,” “Then I’ll Be Happy,” “Wah Hoo,” “When My Dreamboat Comes Home,” and a list a mile long that appeared in such Broadway shows and movies as George White’s Scandals, Earl Carroll’s Vanities, Many Happy Returns, and Shine on Harvest Moon. Cliff Friend had a lot on his plate. He probably didn’t miss half the royalties on one of his first songs. After Hank did the song, it was done by about everyone in country music. Sonny James brought it back to the country charts in 1957 and Floyd Cramer charted with an instrumental in 1962. The British crooner Franklfield charted with it in 1963. For an old 1922 vaudeville tune, “Lovesick Blues” has had a pretty good run. Now someone needs to bring that early verse about the trip to the doctor. I’d be glad to give it to them . . .

2004 Adams Avenue Roots Festival (now called Adams Avenue Unplugged)

The 31st Adams Avenue Roots Festival is coming up May 1-2, and for me, it’s as always a collection of old friends I see too infrequently and people who I’ve wanted to see for awhile.

I first ran into LPs by Clyde Davenport back in the 1970s, and from that time forward, he’s been on the short list of those old-timey performers and musicians that I’d like to have at any festival. Clyde plays fiddle and both clawhammer and finger-style banjo. He was brought up on the music of Dick Burnett and Leonard Rutherford and makes his home in Whitleyville, Tennessee (in the Cumberland Gap area). Clyde is thought to have the largest repertory of solo fiddle tunes among any southern mountain fiddler. He plays tunes in an archaic style, characterized by cross tunings, elaborate bowing, and eccentric meolody lines.

These were fiddle tunes made for listening (“Kittypuss,” “One-Eyed Rosie,” and “Jenny in the Corss Patch”) that dropped from general circulation around the turn of the last century (that’s 1900, folks) as ensemble sounds became increasingly popular.

Clyde developed some more progressive phrasing while playing in a country bluegrass group, The Radio Pals, in Muncie, Indiana during the late ‘40s. Interestingly, this almost never shows up in his breakdown numbers, where his approach is clean and traditional.

Clyde is equally versatile as a banjo player and can choose from clawhammer, two- and three-finger traditional styles, or Scruggs style to accompany a fiddle tune. He’s been called one of the most important living traditional musicians. You won’t want to miss him, especially if you play banjo or fiddle. You’ll kick yourselves if you do.

I last saw Jimmy and Nancy Borsdorf (who call themselves Hawks and Eagles) when they played at the twentieth Roots Festival in 1987. They bring their mix of old-timey and contemporary guitar and fiddle songs back to San Diego in May. They are true musicians, which means they play a lot of stuff and they play it well. You won’t want to miss them either.

Finally, there is the Mexican Roots Trio, who have been called the New Lost City Ramblers of old-time Mexican music. I only recently heard Joel Guzman, Sarah Fox, and Max Baca, but they come across like a great old 78 by Lydia Mendoza or Los Madrugadores. These young Chicanos are helping preserve cultura, herencia, y raices. Natives of San Antonio, Texas, they are coming all the way to San Diego for the Roots Festival. Keep watching these pages for more information on the 31st Roots Festival on Adams Avenue.

Recordially,

Lou Curtiss

Note: Reprinted from the San Diego Troubadour, March 2004