Recordially, Lou Curtiss

Rosie and Me

I first heard Rose Maddox on Town Hall Party sometime around 1953. She was calling herself the Sweetheart of Country Swing in those days and performing with brothers Cal, Henry, Fred, and Cliff as the Maddox Brothers and Rose. I was a 14-year-old kid when I went to the Town Hall with my folks for the first time. (Over a ten year period, I was probably at Town Hall more than a hundred times.) I was impressed enough to start looking for them on the radio. It didn’t take long for me to find them on XERB out of Rosarito Beach, on an L.A. station (I forget which one), and live right in my own South Bay neighborhood. They would be at the 21 Club in National City where I could stand in the alley at the side of the stage and listen or even go inside if I promised not to drink since I was underage.

I got to know Rose and Fred a little, and Cal used to call me “the little bastard.” Henry mostly ignored me (Fred used to call Henry “the working girls’ friend” and I guess he was.) and Cliff had left by this time to form his own group, who I saw once at Town Hall. The guitar player in the band was Roy Nichols, who mostly palled around with Henry and Cal, so I never got to know him very well.

The Maddox Brothers and Rose played at other places in San Diego, including the Bostonia Ballroom east of El Cajon. I saw them twice there, once on a bill with Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys when Rose got up and sang a tune or two with Bob, and another time at an ice skating place downtown when they shared the bill with Ernest Tubb. I think I saw them once in a parade — maybe the Mother Goose Parade in El Cajon — and once at the Del Mar Fair.

By the late 1950s the Maddox Brothers and Rose were out on the road. I remember seeing them on Doye O’Dell’s Western Varieties television show around 1957 for the last time. They had sold their interest in the two 21 Clubs (the other one was in Oceanside) and by late 1958 they had quit performing altogether.

Around 1962 when Rose was starting a solo career, I saw her a couple of times at Town Hall with her brother Cal and solo with her new band at the Westerner, a club in National City. Opening for her was a young guy named Buck Owens, with whom she had recorded a duet (i.e., two-sided) hit: “Loose Talk” and “Mental Cruelty.” Owens wouldn’t last long as an opening act, as he was on the way up with two or three hits already under his belt (One of them, “Excuse Me, I Think I’ve Got a Heartache,” went to number two.) and was just a year away from his incredible run of ten number one hits in a year and a half. Rose was doing alright herself during that time with a number three hit, “Sing a Little Song of Heartache,” and classic LPs, such as The One Rose and Rose Maddox Sings Bluegrass, plus a fine gospel album, which she always called Rosie’s Revival Hour. During the next few years I was going to college, playing music myself and in general widening my musical tastes, and, while Rose’s records remained in my collection, I didn’t get a chance to see her again for a while.

In 1975 my parents, George and Mardelle Curtiss, were on vacation, driving up the West Coast and through the little town of Medford, Oregon. My Dad always liked to take old country roads “to find out where they went.” That is just what he was doing when he saw the name Rose Maddox written on a mailbox. Remembering that I was interested in Rose in the old days and that I was now doing a festival that had already featured country musicians from the same era — like Merle Travis, Cousin Emmy, Bill Monroe, and Cliff Carlisle — Dad wrote down the address and brought it back to me.

After I had written to Rose, she sent back a letter saying she had recently retired from music but she might consider it, since she had never played at a folk festival before. I called her and we talked for about an hour. I told her about the boy in his early teens who listened to her and her brothers, and she told me about being a teenager herself when she started singing on the radio in Modesto during the 1930s. She talked about doing shows with Woody Guthrie when he lived in California and how he gave the Maddox Brothers and Rose their first big hit, “The Philadelphia Lawyer.” By the end of the conversation, I’d talked Rose into playing at the ninth San Diego Folk Festival. She also performed at the tenth festival and by that time had a new LP out and a revived career. That year she told me that she was grateful to me for getting her going again. I told her the credit should go to my Dad for writing down that address. She then said, “Bless the people who are curious about old country roads and people who are persuasive on the telephone.” It’s a great feeling when you find one your musical heroes to be as complimentary as Rose was.

Rose went on to a second career with Chris Strachwitz’ Arhoolie Records, who reissued many of the Maddox Brothers and Rose’s early 4-Star stuff and did some new recordings as well, which led to the Bear Family box sets of the Maddox Brothers and Rose’s Columbia sides and Rose’s early Capitol sides. (I understand that the Maddox Brothers and Rose’s complete 4-Star recordings is available on the Bear Family label as well.) Arhoolie has also issued three CDs of the Maddox Brothers and Rose’s radio transcription sides. All anyone could want and, of course, I wanted it all.

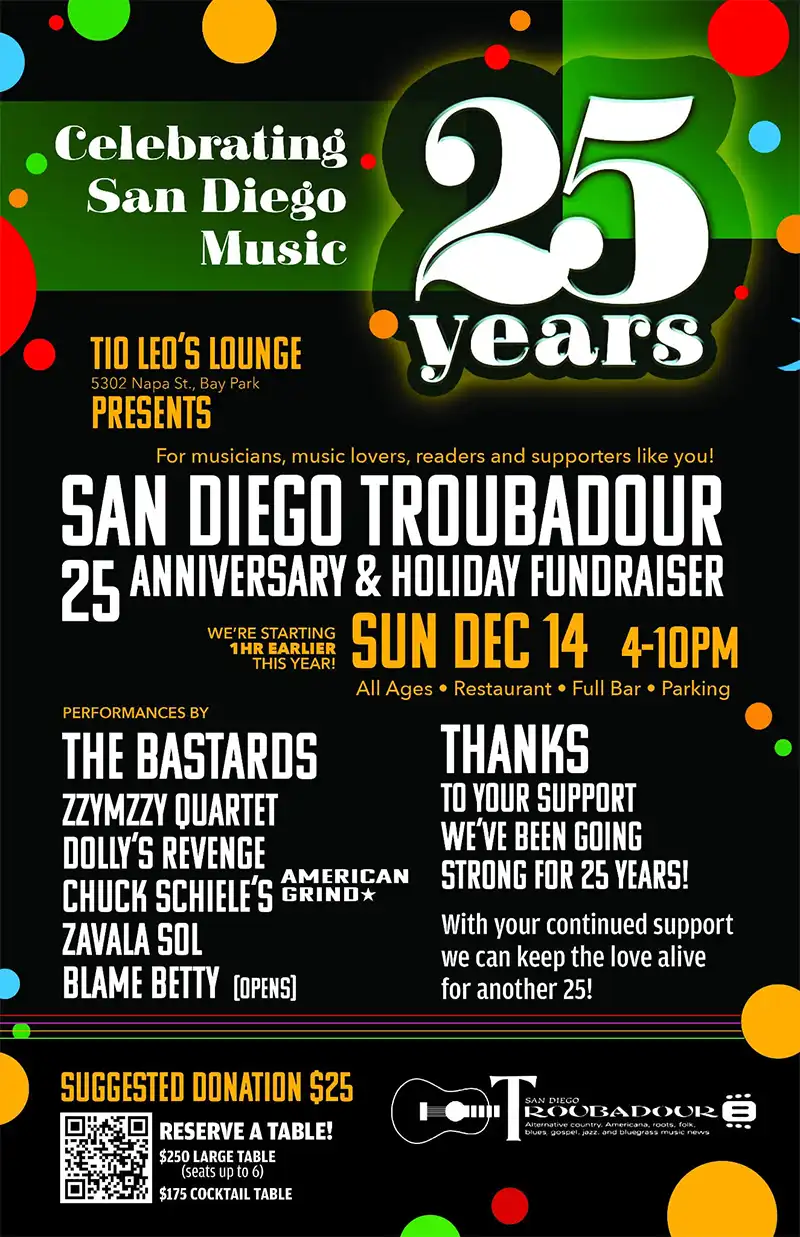

Rose appeared at folk and bluegrass festivals all over the country during the following 25 years, appearing in San Diego for the last time on May 4, 1996 at the 23rd Adams Avenue Roots Festival. (Note: San Diego Troubadour writer Paul Hormick played bass in her band that year.) I talked to her once on the phone after that festival (just a short inquiry about her health) and received a book about her life called Ramblin’ Rose in the mail, which was inscribed “To Lou, my friend. With love, Rose Maddox.”

Rose was one of the great ladies of country music. I place her right up there with Patsy Cline, Molly O’Day, Wilma Lee Cooper, and Wanda Jackson, but Rose heads that list. Woody Guthrie called the Maddox Brothers and Rose the “best hillcountry string band in these 48 states of ours” back in 1949, singling out Rose and her brothers as “the only band on the musical trail today to master a range wide enough to do “Milk Cow Blues” as well as Sister Bessie Smith and “Tramp on the Street,” in a way that outdoes the classic Carter Family.”

In all my dealings with Rose, like the closing of her book says, “she has never demanded, taken, or expected to be given anything. Rose always simply does what she must, and has always done that better than just about anyone else.” I remember seeing her at a club where she was provided with a less than perfect backup band. She turned around and finally, in exasperation, said, “Can’t none of you play hillbilly?” turning the second rate backup into the humorous part of the show.

It’s kind of strange that today Rose is considered an important cog in the country sound from the Bakersfield area, since she was also an important part of our city. In fact, she made her home here during a few of the peak years of her career. This was one special lady. She won’t be forgotten.

RIP KEN SWERILAS

I first met Ken Swerilas when he owned and operated VINTAGE MUSIC on E Street back in the 1960s and he invited me over to his place to one of his Saturday Night picking sessions (also 78 rpm listening sessions). Ken first brought Mississippi bluesman Sam Chatmon out to San Diego in the late ’60s, and it would be the beginning of Ken’s helping me bring out some amazing old time musicians to San Diego over the years, including Sam and Kirk McGee, Wade and Julia Mainer, and Cliff Carlisle and Wilbur Ball. He was always helpful with letting me know who among the old timers was still around, and on several occasions he made the contacts for me. He was also critical when my festivals got a bit too contemporary for his taste.

He had an amazing collection of vintage 78s, which he was always ready to turn me on to. He took an old country folkie like me and made me into a vintage blues, jazz, cajun, and vaudeville buff as well. The man loved to answer musical questions that I was always prepared to ask.

Ken was one of San Diego’s little known musical behind-the-scenes treasures. I’ll miss him and so will the record-collecting world.

Recordially,

Lou Curtiss