Yesterday And Today

Angelically High and Lonesome: Remembering PHIL EVERLY — January 19, 1939 – January 3, 2014

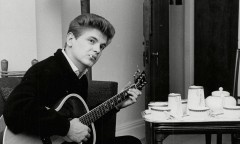

Phil Everly in the late 1950s.

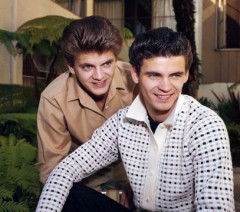

Phil and Don Everly in the early days of their success.

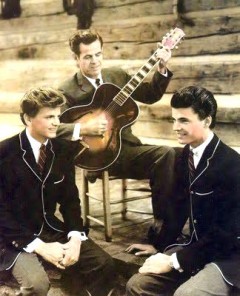

Father Ike Everly with the brothers

Phil in his later years.

On January 3, 2014, Phil Everly, of the legendary Everly Brothers, passed away in Burbank, California from complications due to a lifetime of cigarette smoking that resulted in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. He was two weeks shy of 75.

Along with his older sibling Don, the Everly Brothers significantly changed the course of popular music during six short years at the top of the charts with their unique blend of country, western, rockabilly, and the blues — essentially personifying as much as anyone what many people have called “rock and roll music” for the past five plus decades. Their influence is incalculable and it would be impossible to imagine the second half of the 20th century without their close knit, celestial harmonies. Much like the Wilson brothers (and many others), there’s no mistaking the effects that sharing the same DNA has upon harmony singing. Although they’re two full years apart in age, sonically they might as well be perfectly matched twins with Don typically taking the bottom register lead vocal and Phil soaring in perfect parallel formation above him. In a word, what they sound like is exquisite timelessness, laced with the sensation of time standing still.

Phil and Don are the sons of Ike and Margaret Everly. Don was born (February 1, 1937) in the now defunct hamlet of Brownie, Tennessee, and Phil (January 19, 1939) in Chicago, Illinois. They spent their childhoods growing up in Shenandoah, Iowa and Knoxville, Tennessee, before attending Indiana State University. Ike was a superb guitarist in his own right (as well as a contemporary of Merle Travis) and taught his sons how to play the guitar and sing before either of them had reached the age of ten. During their time in Iowa, Ike hosted his own radio program and the quartet often performed as the Everly Family. But no matter where their travels took them, all roads eventually led back to the Appalachian hills of Muhlenberg County, Kentucky (the world’s largest producer of coal, where the majority of the Everlys live), which also serves as ground zero for the unique musical hybrid that the brothers brought to the world.

In the 1984 BBC documentary Songs of Innocence and Experience, the Everlys shared what it was like to come of age in that place and time. Phil: “It was the best of times to sit on the porch and swing up at our Aunt Myrtle’s and Uncle Roland’s, Nadine’s and GW’s. We would be playing at night and when we got a little older we started singing a little louder because sometimes that music would attract some of the young girls [laughs] and you had a chance to meet somebody that way.”

That “high and lonesome sound” of the Kentucky mountain range is legendary in its sense of conveying a particular flavor of emotion — what some might refer to as being melancholy, although Phil didn’t see it that way. “I don’t really call it melancholy,” he said. “I think it’s just a basic truth that life is full of both happy and sad events — you know, love and death, losing and winning, and in this area and this music, people are very honest about it. When you’re happy, you sing a happy song and when you’re sad, you sing a sad song and you allow yourself to feel.”

During their time in Knoxville the Everly Brothers came to the attention of family friend Chet Atkins. After transitioning as a quartet with their parents into a self-contained duo, Atkins introduced them to publisher Wesley Rose. Rose was not only impressed by their crisp harmonies but also with their original songs and he arranged for both a publishing contract with Acuff-Rose and a recording contract with Cadence in 1957. Shortly thereafter they relocated to Nashville.

Phil: “Nashville was pretty much the mecca of country music — of course, we were doing a strange brand of country [mixed with] some of the other things that we had been listening to.”

Don: “Phil and I wanted to get on records — any way that we could do it was what we wanted to do. We liked all kinds of music at that point. We were trying to make it in the field and appearing at the Grand Ole Opry was considered ‘stardom.’ Hank Williams, to me, was the first real rock and roll star. To me, he wasn’t a real, pure, down-home country musician. He was out there. I think it was a combination of that and black R&B that made rock and roll. And there was something so glamorous about that cowboy suit with the white piping and the Cadillac, the music, and the whole thing.”

Songwriter Boudleaux Bryant: “Chet Atkins had told me that he knew two great singers, a couple of brothers that were a great duet and that if he found the right material he might record them. But that’s a pretty hazy thing to try and go into full production with as far as writing goes [laughs].

“But when I first heard them I thought they were wonderful. They had a different quality. There had been many duets before but they had that little extra something and when the two voices came together there was an abstract third ‘something’ happening that made them just a little touch above most anybody I’d ever heard.”

As songwriters, Felice and Boudleaux Bryant supplied Phil and Don with their breakout hit “Bye Bye Love” in March of 1957, where it reached #2 on the pop charts. For the next three years the two couples were an unstoppable team, racking up classic after classic with the following singles: “Brand New Heartache” (1957), “Devoted to You” (#10 in 1958), “Problems” (#2 in 1958), “Poor Jenny” (#22 in 1959), “Take a Message to Mary” (#16 in 1959), “Sleepless Nights,” “So How Come (No One Loves Me),” “Love Hurts” (all three from 1960), in addition to a trio of #1 smashes with “Wake Up, Little Susie” (1957), “All I Have to Do Is Dream” (1958), and “Bird Dog” (1958).

Don: “As soon as we could afford it we went and had suits made in New York. We quit dressing in what they call the ’50s style now because everybody was wearing it. Your father was wearing it, first of all [laughs]. The last thing you wanted to look like is your father. We went strictly Ivy League: three buttons, button-down collars where everything had a buckle in the back, including your shoes. [laughs]

“Yeah, the whole clothes thing and then the haircuts. I’ll tell you, the hassle over haircuts was just immense. The first time we walked through the streets of Hong Kong in the early ’60s, before the Beatles, you’d stop traffic. Literally stop traffic. People would stop. And stare.”

Phil: “I believe Elvis Presley is still a kind of king. If he hadn’t kicked down all the doors none of us could have gotten through.”

Don: “Music was going through a real major change then. The era of orchestras was ending. Records were beginning to rock and roll and you either hated it or loved it.

“And we called it rock and roll because of Alan Freed, he named it rock and roll and those were the records that we listened to. I called Little Richard rock and roll. But I also called what Buddy Holly was doing rock and roll.

“At the end of the ’50s, it was pretty tumultuous being on the road. The big package tours that we would get on — you would have 15 to 20 acts and you were playing to 100,000 people a night in these big coliseums, doing three songs, with pandemonium — no one could hear a thing; everybody’s screaming and yelling from the time it started ’til the time it ended.”

Even though Phil says that performing on a package tour with the likes of Eddie Cochran and Buddy Holly was like “being in a college fraternity,” it wasn’t all fun and games, especially when it came down to the business side of music.

Don: “It was Us against Them, always. Very few of those rock and rollers from our life ever wound up with any control over anything they did. It wound up that a publishing company had control over what was being released and we disagreed with that entirely. If your publishing company controls your releases they’re going to want their songs to be released. So, it all came down to artistic freedom. We had to have it and we got it. But, in the process, all of the people that we were dealing with had to go by the wayside in order for us to pursue it. Because rock and roll wasn’t going to stand in that one spot. And let’s face it, it didn’t.”

After a three-year stint with Cadence, the Everlys signed a lucrative contract with Warner Bros. Records in 1960. For another three years the hits just kept on coming. Their first single for their new label “Cathy’s Clown” (written by Don and Phil) sold eight million copies, becoming the duo’s biggest-selling record.

Other successful singles followed: “So Sad (to Watch Good Love Go Bad)” (#7 in 1960 and written by Don), “When Will I Be Loved” (#8 in 1960 and written by Phil), “Walk Right Back” (#7 in 1961), “Crying in the Rain” (#6 in 1962, written by Howie Greenfield and Carole King), and “That’s Old Fashioned (That’s the Way Love Should Be)” (#9 in 1962 and their last Top 10 hit).

In addition to parting ways with Cadence and their publishers at Acuff-Rose, the Everlys career hit a bit of a speed bump for six months when they enlisted into the United States Marine Corps Reserves in November of 1961, rather than being called up into the Army for two years of active service.

Phil: “I had thought this through and the marines sounded like death to me and Don said to me, ‘Yeah, but you know they got those shiny helmets.’ [laughs] I never saw a shiny helmet. But one thing led to another and we wound up there.”

Don: “It was great training. It was something that I think, all in all, helped us in that period of time when life could have been a lot more difficult.”

If the Everlys began the ’60s commercially with a bang, they would soon find themselves considered passé, due in part to the new wave of troubadours led by Bob Dylan and the incoming British Invasion. The irony was galling — it was as if Phil and Don had hosted the greatest shindig imaginable for six years and after getting the rock and roll party energized they were told to leave their cooler full of cokes on the back porch and take a hike.

Don: “We turned around twice and all of a sudden you had to be English. It was ‘in’ to be English, especially with the Beatles and then the Rolling Stones. A lot of good came out of it, but it dominated the airwaves for quite a period. Everybody was saying, ‘Geez, the Beatles sound an awful lot like you,’ and I said, ‘Yeah, well what can I do about that?’

“The other side of the music business is you became very ‘square’ if you didn’t get stoned and you didn’t have the really long hair and you didn’t have that element about your ‘mystique.’ I was listening to the music and to me it wasn’t revolutionary, it was just louder and had more tracks.

“They didn’t know what to think of us at all. I mean, even if we didn’t wear tuxedos they didn’t know what to think of us. They knew that we were from the ’50s, and that was not the ’60s, you know? It was that attitude and our songs didn’t have any double meanings so we had a hard row to hoe within that era; we also worked Las Vegas and that was really bad. Music quit being something that you could earn an honest living by; it had to be a ‘social movement.’”

Phil: “I always felt that the ’60s were phony. Through that psychedelic period you still have to get records played and when everybody has an attitude, like they’re going for that sort of ‘political reform.’ I think that the ’60s was a very bad period for music.”

Even though the Everlys continued to record well into the 1980s, the hits had pretty much dried up in the United States after 1964. In the classic tradition of living a country western/rock and roll lifestyle, both brothers went through a period of drug abuse and became addicted to methamphetamine. They pursued various projects both solo and together in the early ’70s, eventually drafting together a touring band led by an unknown pianist and composer named Warren Zevon. Guitarist Waddy Wachtel would join the group shortly thereafter.

Warren Zevon: “The Everly Brothers were looking for a piano player and when I met Phil he said that I could audition for them. Don and Phil were both at the audition and I played ‘Hasten Down the Wind.’ Phil said, ‘Can you play like Floyd Cramer?’ I said, ‘You bet I can.’ Without asking me to play another note, they hired me.”

Zevon and Wachtel enjoyed three years on the road with the Everlys, but by 1973 the brothers decided that they needed a rest from the grind as well as each other. What happened next is one of rock’s most infamous incidents (as recounted in Zevon’s biography I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead).

Crystal Zevon: “Don and Phil were breaking up, but they had contracted to play a three-night gig at Knott’s Berry Farm. Warren wanted me to be there for the Everly Brothers’ last performance.”

“It was July 14, 1973. We arrived and Don was drinking heavily. I’d seen Don perform with the flu and a temperature of 103 degrees. I’d never heard him hit a sour note or be anything short of professional in front of an audience. But, this night, he walked onstage dead drunk. He was stumbling and off key and I remember Phil trying to restart songs several times. It was embarrassing.

“The fourth or fifth song they did was “Wake Up, Little Susie,” and Don was forgetting people’s names and insulting the audience and Phil. Finally, Phil stormed offstage. He smashed his Gibson guitar and said, ‘I quit.’ It was stunning.”

Even though it took a decade, when the duo later reunited in 1983 and performed a triumphant comeback show at London’s Royal Albert Hall, the brothers had learned to put things into perspective. Phil: “Don and I had toured for almost 16 years straight and we’d been working for years and years before that, so we’d done a lot.”

Don: “We were working seven, eight, nine months a year — and if you do that for a period of 20 years you’ve got a big chunk of your life spent traveling, being a duet in the music business. Especially when you do it like Phil and I do — with close harmonies, nose-to-nose. That puts a lot of strain on the relationship.

Phil: “The real pressure for us was the business — we had much more to worry about then some sort of sibling rivalry continuing past adolescence all the way into adulthood. That’s a simplistic kind of view point of what led to the ultimate end of the Everly Brothers, but it’s untrue.

“You can sing the blues at 20 and be blue. You can be sad at 20. And when you sing the blues at 40 you’ve got 40 years of blues and 40 years of sad and it’s sadder, but then at 60 it will be some other way. The family made music, dad made music, and he taught us the craft, and actually, I probably believe that it’s a family business or otherwise I wouldn’t have taught my sons and passed that on. I would like to see my grandchildren learn to play just because it’s what my dad taught me.

“His guitar got him out of the coal mines of Kentucky and the guitar he gave us got us all the way to London and the guitar that I’ve given my son I think is doing very well for him with the girls. So, if he can do the same for his son I think it’s a grand kind of thing. But we were, basically, carrying on what the family did.

“I approach my life in this way: yesterday is yesterday and if you take all of your past mistakes and drag them into your present, you’re only going to confuse your present. Tomorrow is more important than your yesterday.”

Don Everly said he didn’t expect to see the day his brother would pass.

“I loved my brother very much,” the 76-year-old wrote. “I always thought I’d be the one to go first. The world might be mourning an Everly Brother, but I’m mourning my brother Phil Everly. My wife Adela and I are touched by all the tributes we’re seeing for Phil and we thank you for allowing us to grieve in private at this incredibly difficult time.”

Phil Everly is survived not only by his brother Don, but also his wife Patti and his two sons, Jason and Chris, both singers and songwriters.