Yesterday And Today

Pete Seeger: Precious Friend

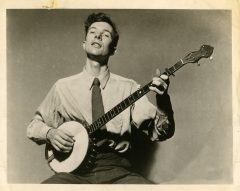

The one and only Pete Seeger (1919-2014)

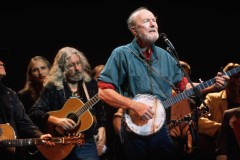

Seeger with Arlo Guthrie and friends

Pete and Toshi Seeger

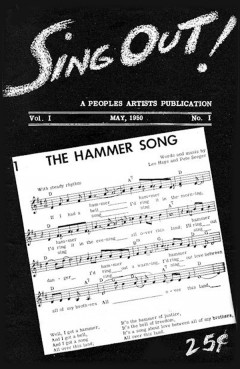

Sing Out! magazine was Seeger’s creation and is still being published today.

Just when I thought all was lost

You changed my mind

You gave me hope

Not just the old soft soap

You showed that we could learn to share in time

(You and me and Rockefeller) I’ll keep

plugging on

Your face will shine

Through all our tears

And when we sing another little victory song

Precious Friend, you will be there (Singing in harmony)

Precious Friend, you will be there.

—Pete Seeger

Pete Seeger, America’s tuning fork, the folk singer

who revived the five-string banjo

who taught “We Shall Overcome” to Dr. Martin Luther King at Highlander Folk School in New Market, Tennessee and turned an obscure Georgia Sea Island hymn into an international anthem for freedom from the March on Washington to Tiananmen Square

who saved the most polluted waterway in the country with a replica he built from a 19th century schooner and made the Hudson River run clean again

who fought the House Committee on Un-American Activities tooth and nail, refused to name names on the basis of the First Amendment and six years after he was sentenced for Contempt of Congress saw his conviction overturned by the United States Supreme Court

who popularized not only his own songs but an entire library of American folk music

who single-handedly built Folkways Records into a national institution now preserved by the Smithsonian

who put the songs of the King of the 12-String guitar Huddie Ledbetter and the Dust Bowl Balladeer Woody Guthrie on the lips of students from California to the New York Island

who stood up to the Ku Klux Klan with Paul Robeson at Peekskill, New York in 1949 at the most dangerous concert ever held in this land, and proudly displayed the rocks they threw through his car window in the fireplace of his log cabin in Beacon

who taught Dave Guard of the Kingston Trio and Eric Darling of the Rooftop Singers and Alex Hassilev of the Limelighters, and Don McLean and Michael Cooney and my friend “Banjo” Fred Starner and a thousand lesser known and unknown musicians like me to play the long-neck banjo with his mimeographed instruction book How to Play the Five-String Banjo

who taught audiences around the world to sing along with their own folk music

who made a children’s book based on his cante-fable Abiyoyo from an old South African collection of stories his father gave him when he was ten into a New York Times bestseller

who introduced the songs of “Woody’s Children” Bob Dylan, Tom Paxton, Phil Ochs, Peter La Farge, Len Chandler, and Malvina Reynolds to a new generation of fans and singers through the Newport Folk Festival, which he helped launch from his living room in 1958

who created the two most important singing groups in American folk music history: the Almanac Singers and the Weavers

who turned Leadbelly’s theme song “Goodnight Irene” into the number one song of the half century in 1950 according to Life magazine — which remained in the top spot on the Hit Parade for 17 straight weeks — longer than any song by Elvis Presley or the Beatles or the Rolling Stones or anyone else until 1975

who was told by Jack Linkletter of the shameful ABC show Hootenanny (a word invented by Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger during their Almanac days) that he, and I quote, “couldn’t hold an audience,” which was why they wouldn’t book him

who was similarly blacklisted by all the major networks including CBS for 17 years after the Weavers were blacklisted by Red Channels in 1950 until the Smothers Brothers invited him onto their Comedy Hour — only to be told that he couldn’t sing “Waist Deep in the Big Muddy” by CBS censors because “someone might think he was referring to President Johnson,” but then was invited back by the Smothers Brothers in 1968 when he triumphantly sang the best antiwar protest song ever written — by a World War II veteran

who managed to make a living after he was blacklisted in the 1950s by singing at elementary schools and colleges and summer camps where he taught an entire generation of students to appreciate their own musical heritage and history through the songs that were born out of social struggle, until those students grew up and became the rebels of the 1960s

who thereby exempted Pete from their own rule, “Don’t Trust Anyone Over 30”

who raised five children on a folk singer’s wages until his own songs like “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?” and “Turn, Turn, Turn” and “Kisses Sweeter Than Wine” and “If I Had a Hammer” made so much money from hit recordings by the Kingston Trio and the Byrds and Jimmie Rogers and Peter, Paul and Mary that he was embarrassed by it and refused to look at his own bank balance again and let his wife Toshi handle all their financial affairs

who paid his own way to all of his benefit concerts, paid for his own tickets to the same concerts, and then made a substantial donation himself to add to the funds he raised

who told his manager Harold Leventhal, “I don’t want to know what they are paying me to perform; that’s your department”

who quit the Weavers after their 1955 Christmas Eve Reunion Concert at Carnegie Hall — the one that was recorded and released on Vanguard Records and launched their new label — the label that then recorded Joan Baez and Buffy Saint Marie and all the Newport Folk Festivals — and started the Folk Revival of the 1960s — because they agreed to star in a cigarette commercial and Pete refused to have his name used to sell cigarettes or any other commodity but the music he stood for

who then went back out on the road as a solo folk singer

who had nothing to sell and refused to sell out

who showed what one life lived with integrity could accomplish and finally reaped the rewards of his convictions with the Kennedy Center Honors and hearing President of the United States Bill Clinton refer to him as “an inconvenient artist” when bestowing the National Medal of the Arts — our government’s highest honor for the Arts — on him in 1993

who was then invited by President Barack Obama to perform on the National Mall for his 2008 Inauguration where he sang all six verses of Woody’s “This Land Is Your Land,” including the one that says:

As I went walking

Out on that highway

I saw a sign say, “No Trespassing,”

But on the other side

It didn’t say nothing

That side was made for you and me!”

who fell in love with the five-string banjo in 1935 when he was just 16 years old and his folklorist and ethnomusicologist father, Charles Seeger, took him to the Asheville Folk Festival in North Carolina and he heard the Appalachian Minstrel Bascom Lamar Lunsford play it for the first time, and ever afterward told his audiences, “Don’t learn to play the banjo from me — learn it from the people I learned it from — Pete Steele and Uncle Dave Macon and Doc Boggs and Wade Ward and Frank Proffit — always directing us back to his sources and away from himself

who often referred to himself as “a born-again agnostic”

who taught young kids up and down the river when he sailed the Clearwater along the Hudson River to raise money and awareness of what it would take to clean it up, and inspired a new generation of environmental activists to do just that, including Bobby Kennedy’s son Robert F. Kennedy, Jr

who started the group River Keepers to carry on Pete’s pioneering work

who founded not one but two great folk music magazines People’s Songs Bulletin and Sing Out! to publish both old and new songs from across the country and around the world — such as the Spanish Civil War songs he rescued from oblivion and brought to Folkways’ Moses Asch to record when he was on a three-day leave from the island of Saipan during World War II — where he met future KPFK broadcaster Mario Cassetta and commandeered him to come to Los Angeles after the war to start a chapter of People’s Songs here so they could claim with Woody that their little magazine went all the way “from California to the New York Island”

who inspired me to pick up a banjo when I first heard him play Uncle Dave Macon’s “Cumberland Mountain Bear Chase” on an old Stinson Record — from their American Folksay Series — and to think that one day I too could make a living as a folk singer

who showed us how and told us why

who sang Bob Dylan’s “Ye Playboys and Playgirls” with him at the 1963 Newport Folk Festival and introduced him to a national audience and sang Dylan’s “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” on his world tour later that year to give him international exposure (both performances were recorded, the first on Vanguard Records and the second on Columbia Records)

who sang Tom Paxton’s “Rambling Boy” with the Weavers at Carnegie Hall also in 1963 (he eventually forgave them for the cigarette commercial, like he forgave Burl Ives for naming names before HUAC and appeared with him in concert at Town Hall in New York City to show that friendship is sometimes more important even than principle and people can make mistakes and be forgiven), and

who made a hit out of Malvina Reynold’s “Little Boxes” — giving them all a platform for the rest of their careers

who wrote “This Machine Surrounds Hate and Forces It to Surrender” on his banjo

who paid tribute to his devoted wife Toshi after she passed away last year by saying “she was the brains of the family”

who was still chopping wood out behind their cabin just ten days before he died “of natural causes”

who stood out on a street corner in Beacon on the Hudson in upstate New York every week even during their snowy winter with just an American flag and a small sign that said simply, “Peace,” during the entire Iraq war, inspiring me to do the same with Neighbors for Peace and Justice in Studio City

who made a fabulous three-egg cheese and mushroom omelet with strawberry shortcake for dessert for me when I stayed over at his log cabin in 1976, a newly fledged songwriter

who drove up to his cabin from my graduate school studies at SUNY-Binghamton to show him my songs and then quietly put them back in my guitar case when I heard him sing “My Rainbow Race” for the first time during the Hoot after their regular monthly meeting of the Beacon Sloop Club (for which I had timed my pilgrimage) and thought “that’s the most beautiful song I’ve ever heard,” learned it on the spot, and realized my songs needed some more work before I would ask him to listen to them

who showed me how much he loved Toshi when he came out to perform at the Barn Folk Concert Series at UC Riverside with both Mike and Peggy Seeger — the first time they had all performed together in a quarter century — and the one time Toshi left his side I heard him sing to her like a bird over the heads of hundreds of concert-goers outside the Barn, just to establish where she was and reconnect, his fabled Adam’s Apple bobbing up and down and his voice doing somersaults until he heard her sing back to him, “Pete, I’m here!”

who inspired Dylan to write “and the saintliness of Pete Seeger,” in the album liner notes to Bringing It All Back Home

who, when the networks banned him from appearing on TV in the country he went to war to defend during World War II — while the chicken hawks on HUAC got away with calling this most American of artists “Un-American,” started his own public television show “Rainbow Quest” to bring his favorite fellow artists and America’s folk songs to yet another new generation of listeners and viewers

who, like Walt Whitman, heard America singing and for over 75 years gave Americans their most sacred national heritage — the songs and stories from the unknown cowboys and sailors and loggers and housewives and slaves, former slaves, industrial workers and coal miners and farmers and immigrants and rebels and yes outlaws, too, the anonymous poets’ voices that make up the Great American Songbag

who was and always will be America’s greatest folk singer, has died. He was 94 years old and forever young.

How can he keep from singing, “Toshi, I’m here!”

Rest in Peace.

REPRINTED FROM FOLKWORKS WITH PERMISSION (www.folkworks.org)

Ross Altman has a Ph.D. in English. Before becoming a full-time folk singer he taught college English and Speech. He now sings around California for libraries, unions, schools, political groups and folk festivals. You can reach him at Greygoosemusic@aol.com