Recordially, Lou Curtiss

The Wolf

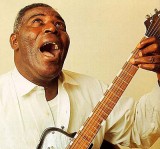

Howlin' Wolf

I first saw Howlin’ Wolf in 1963 on his home turf at Big Duke’s Club on Chicago’s West Side, and later that same year at the Newport Folk Festival. The last time I saw him was at The Palace in San Diego in the late ’60s. Wolf was a big Mississippi blues singer in the tradition of Charlie Patton, Bukka White, Robert Johnson, and so many others. He had enough of Chicago via Memphis in him to have erased submission or compromise, but not so much that he ever really got rid of his country roots. He never became the bi-cultured urbanized artist that his contemporary Muddy Waters became. He remained what his name implied: a voice from the backwoods, casting incantations to a country sky.

The sleeve of his first LP for Chess records, though simple and obvious enough, got it right — a plainly drawn wolf howling to a chilly moon. I knew Wplf’s records well. I think the first Chicago Blues 45rpm record I ever bought was Wolf’s “Sittin’ on Top of the World/Poor Boy” in a thrift store about 1957. After that I acquired everything I could get my hands on — earlier records and susequent ones. It strikes me as quite sensible because Wolf’s singles were something special in their context. He was almost without competitors, the bluesman who went on turning out great singles, not great albums, but singles in the true commercial tradition. Not that they were true commercial successess. I don’t think I ever bought records in those days because they were commercial successess. I’d hear a record by an artist I liked and then I had to have everything by that artist. With Wolf I was seldom disappointed. His records were fashioned for a particular market, not yet affected by white patronage, and they avoided all the pitfalls of the business: repetitive follow-ups, capitulation to dance fads and so on. What was most remarkable was that they combined an extraordinary traditionalism: Deep South imagery, old time blues motifs and melodies, with a loud modernity of arrangement.

For a few years, Wolf turned out glorious records almost automatically. The series began about the time he moved to Chicago in the mid ’50s with tunes like “Smokestack Lightning,” “Natchez Burning,” “I Asked for Water (She Gave Me Gasoline),” and “Who’s Been Talking.” They continued into the ’60s with “Wang Dang Doodle,” “Little Red Rooster,” “Back Door Man,” and “Built for Comfort.” I could go on and on and cite a whole unedited chunk of his great discography. Controlled force, a high noise level, and material ideal for one of Wolf’s backgrounds and abilities combined in records that scarcely anyone in Chicago could match.

It was with some surprise that I, who at that time had been converted by the Great Folk Scare of the late ’50s, heard in 1963 that the very Howlin’ Wolf I had secretly collected was to appear at the Newport Folk Festival in Newport, Rhode Island. My trip East that year included a stopover in Chicago where the good folks at Jazz Record Mart gave me a guided tour of the local blues clubs, including that first viewing of Howlin’ Wolf. I had heard that his stage act was demonstrative in a manner not every blues enthusiast might be able to absorb comfortably. And that was the case, in familiar surroundings as well as what must have been an unfamiliar venue at Newport. As I was told, Wolf hammed it up no end. After a few moments, I had no doubt that what I had heard was almost unbearably true. He lept around, glared, rolled his eyes, in short, he acted the part he took upon himself years before with his nickname, and only a misplaced delicacy would allow one to be offended by it. As acting no doubt it was broad — Lon Chaney and King Kong rather than Shakespeare. Would you expect anything else?

It was extraordinary stuff for the period. It was loaded with folklore and with references to blues so old as to be folklore themselves. The back-door man, the tail-dragger, the little red rooster, the country sugar mama; characters like these had been creeping and strutting and winging their way through the blues for generations. And here they came again, urged on by excellent bands, with lead guitar men like Hubert Sumlin and, before him, Willie Johnson outdoing themselves with each new record. I often wish there were blues singles now appearing that hit me like those did. “Hit Me” — there’s no better word for it — the way “Tail Dragger,” “300 Pounds of Joy,” or “Going Down Slow” did, or come to think of it a little remarked 1962 track, “Do the Do,” which sounds inconsiderable. but is a wonderful couple of minutes in the middle of a riot.

By the mid-’60s, blues singles were disappearing and Wolf had a new audience. The singles had sold mainly to Wolf’s black audience in the ’50s and early ’60s. With appearences at white boy festivals and promos from the Stones he was starting to appeal to a white middle class audience and those folks bought mostly albums (LPs).

Over the next ten years, he yielded to fashions as they rose. There was an all electric album with reverb and feedback, which Wolf privately referred to it as “dogshit”; a London session for the Rolling Stones and other British rockers, and even a contemporary “Message to the Young” that is as terrible as it sounds. Only “Live and Cooking at Alices Revisited” from 1972 club dates, with musicians from Wolf’s past was surprisingly righteous.

But the Wolf I like to remember is the Wolf of the mighty singles and uncompromising stage presence. Right now, as I write, I’ve just recieved the first four-CD package taken from that Golden Age titled Howlin’ Wolf: Smokestack Lightning: The Complete Chess Masters 1951-1960 on the Feffen label (Hip-O-Select.com). There is supposed to be a second set to come with all the ’60s singles (I can’t wait). These sides affirm the angry maelstrom at the heart of the blues, and that at a time when talk is so often of the mellow and laid back qualities of the music. Chester Burnett, “The Howlin’ Wolf,” is so long overdue for a quality reissue like this one. He is one to be affirmed and remembered.

Recordially,

Lou Curtiss