Cover Story

Fred Benedetti: Turning Points in the Odyssey of a Working Musician

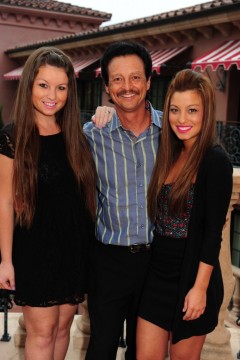

Sitting in his well-appointed Tierrasanta living room, the versatile guitarist Fred Benedetti seems content with where his life’s journey has taken him — as well he should. The wiry 54 year old has been married for 27 years to his wife, Amy; has two beautiful daughters, Regina (age 24) and Julia (age 21), who perform with him as the Benedetti Trio; is a tenured, full-time faculty member in the music department at Grossmont College, where he is head of guitar studies and co-chairs the department; is an instructor at San Diego State University, where he was named the music department’s most influential faculty member of the year in 2001; and has a flourishing career as an instrumentalist, regularly performing solo; as a member of several duos (the Odeum Guitar Duo, with Robert Wetzel; the Benedetti/Svoboda Guitar Duo, with George Jiri Svoboda; and a duo with Peter Pupping featuring a contemporary repertoire); as a member of two quartets (Blurring the Edges, a contemporary jazz group including Peter and Tripp Sprague; and the Zmiros Klezmer Quartet, which plays Eastern European/Jewish music, even though Benedetti is half-Japanese); and in the chamber music ensemble Camarada with Beth Ross-Buckley. On top of that, he surfs regularly.

Benedetti can reflect on accolades that few musicians ever hope to achieve: being selected in 1986 as one of only 12 guitarists worldwide to study under Andres Segovia; performing (as part of the San Diego Symphony) with the famed tenor Luciano Pavarotti and (as part of the San Diego Master Chorale) with the Dave Brubeck Quartet; playing for Mikhail Gorbachev; opening for Art Garfunkel at Humphrey’s; and having some of his many recordings — in various genres — recognized for their excellence. For example, Blurring the Edges’ 1994 self-titled release won Best Pop-Jazz Album of the Year by the San Diego Music Awards, and the Odeum Guitar Duo’s 1998 album Concert Hall Classics was named Best Classical Recording by Acoustic Guitar magazine. The Odeum Guitar Duo’s 2000 album, Forgotten Romance, flew aboard the Space Shuttle Endeavor on its last flight on May 16, 2011.

The animated Benedetti modestly attributes his success to “serendipity” — simply being in the right place at the right time — but underlying his numerous accomplishments is a relentless drive, a passion for all types of music, and a positive attitude that has enabled him to navigate the twists, turns, and bumps in life’s road, which has not always been smoothly paved. Benedetti’s dogged tenacity, resilience, and seemingly tireless work ethic have transformed a series of challenges into an enviable — and eclectic — musical career. Although Benedetti is primarily an acoustic guitarist, he can play anything with strings: electric guitar, mandolin, banjo, even the ukulele. And while his principal métier is classical, Benedetti also performs in the genres of jazz, folk, flamenco, Celtic, contemporary, and even rock. From Mozart to Led Zeppelin, the energetic Benedetti says, “I love all music. I love to play. Music is about creating.” How did Benedetti discover his boundless passion for music?

Benedetti’s father, a serviceman, was a self-taught amateur guitar player who loved to perform classical music and play classical music recordings at home; his favorite performer was Andres Segovia. Benedetti recalls, “The guitar was always around at my house, and I grew up listening to my father play. He never was trained — his family couldn’t afford lessons. So he picked everything up by ear. His ear was tremendous.” “Home” was a moving target for Benedetti. He was born in Sasebo, Japan while his father was stationed there in the Navy and later lived in Hawaii and San Diego. Due to his early exposure to music at home, Benedetti, who was an only child, began playing the guitar — like his father, by ear — at the age of nine. By the time Benedetti started middle school in San Diego, he had developed into an accomplished — albeit untrained — guitar player. It was as a teenager that Benedetti experienced the first of a series of musical “turning points.”

At age 13, in the early 1970s, Benedetti and his childhood friend James Lyons (playing drums) formed a duo they named the Aluminum Birds. Later, when Benedetti was 14, Jeff Pekarek (playing bass) joined them to form an acoustic trio they named San (the Japanese word for “three”). They played contemporary fare (think Cat Stevens and Beatles covers) and some original material they composed on Benedetti’s father’s reel-to-reel tape recorder. One weekend, the aspiring musicians were excited at the prospect of their first paying gig, playing at a party in Balboa Park. They arrived at what they thought was the location of the party but — due to either miscommunication or mistake — they couldn’t find it. The band was stuck in the middle of Balboa Park, with their instruments, and no audience. Crestfallen, they decided that since they had no place else to go, they would get out their instruments and play — just for practice. Situated in front of the lily pond in Balboa Park, with Benedetti’s guitar case lying open on the ground nearby, the trio began to play. Before long, the teenagers noticed that passersby were tossing coins into the case. Even though they had not initially intended to be soliciting donations, the response prompted Benedetti to push the case closer to the performers. Passersby continued to deposit coins and bills in the case. By the end of the day, the teenagers had collected “some pretty good money.” More important, recalls Benedetti, “That was our first introduction to actual public playing.” They loved it.

Encouraged by the reception they received, the enterprising youths decided to become buskers in Balboa Park every weekend for the next several years, typically earning $200-300 per day, playing all day (from 10 in the morning until six in the evening), often until their fingers were literally raw. Benedetti states, “We realized that it was viable for us to be performing musicians,” an inspiration that motivated them to continue their musical journey. Had San become discouraged and packed up and gone home that fateful day when they were stood up for their first gig, it is possible that Benedetti’s destiny would have led elsewhere.

The next turning point came a couple of years later, in high school, when Benedetti’s bass-playing chum, Jeff Pekarek — who, like Benedetti, played by ear — decided to take formal lessons to learn to read music. Pekarek studied under Bertram Turetzky, and within six to nine months Benedetti recalls that Pekarek “had become a monster classical bass player,” improving his innate skills immeasurably and joining the San Diego Symphony at age 16 to become its youngest member. Benedetti decided that he, too, needed to take lessons, despite his fear that formal instruction would diminish his natural technique. After seeing Pekarek’s dramatic improvement, Benedetti recalls thinking, “Hmm, maybe there is something to this. I didn’t even read music. Maybe I should take lessons. I had always felt like I didn’t want someone telling me how to play. But more of it was fear. ” His fears proved to be baseless. Benedetti and his father looked up guitar instructors in the Yellow Pages and found Roberto Torres in La Jolla. “We just got lucky,” Benedetti says. “At the time he was the guy to study with for classical guitar before the Romeros came to town. We had an interview, and I remember him telling me that if I was going to study I’d better not quit on him, because he wasn’t going to teach me for just one lesson or two lessons. He didn’t want to take students who weren’t serious. That was my introduction to formal classical guitar.” Benedetti didn’t quit. He studied under Torres for two to three years until he finished high school. Benedetti had to re-learn everything he knew about guitar technique — the right way. His classical guitar training prompted Benedetti to pursue a music major in college. Had Benedetti not stepped out of his comfort zone and overcome his fear of formal music lessons, he certainly wouldn’t be teaching music today, and his extensive body of studio work (advertising jingles, TV commercials, session recordings, even movie soundtracks) would have been impossible. Another turning point.

During high school Benedetti was still playing mostly popular music, busking in Balboa Park on weekends. That changed after he graduated from high school in 1975. Benedetti enrolled at San Diego City College as a music major, studying under Dr. Paul, who had previously taught at Oxford. The curriculum emphasis was classical music and classical theory. Dr. Paul became a profound influence on Benedetti’s musical career, encouraging him to play lute parts in Dr. Paul’s early music ensemble. “I started playing chamber music with Dr. Paul’s ensemble and through doing that I started meeting other people who were playing classical music in town.” At the same time Benedetti continued to perform with Pekarek (who was now playing in the symphony) and Lyons, only they were now playing a more classically influenced repertoire. One of their main gigs was playing for tips at a vegetarian restaurant named the Prophet, where founder Makeda “Dread” Cheatom encouraged them to pursue their musical careers. She told them they could come in any time and have a free meal as well. Benedetti counts Cheatom among the most influential people in his career development.

While playing at the Prophet, Benedetti met another musician, Lee Ryan, who was teaching guitar at San Diego State. Through Ryan, Benedetti was introduced to a local classical guitar quartet, the Orion Quartet, who needed a new player due to the departure of one of its members. Even though the other members were older and more experienced, Benedetti leapt at the opportunity and soon was performing concerts with the Orion Quartet in and around San Diego and northern California. The quartet, a musical collaboration that lasted for two years (1975-1977), also recorded an album in 1977: Works by Telemann, DeFalla, Rodrigo, and Others. By hustling and being willing to take on new challenges, Benedetti evolved from busking in Balboa Park to playing with experienced classical guitarists in a professional ensemble. Another turning point.

One opportunity leads to another. Benedetti discovered that he had a strong affinity to one of the members of the Orion Quartet, Dan Grant, with whom he formed a classical guitar duo they named the Orion Duo. They became best friends and musical partners, playing together extensively from 1977 through 1984, when Grant tragically died from a heart attack at the age of 30. Benedetti and Grant were so close that Grant was scheduled to be the best man at Benedetti’s upcoming wedding. (Benedetti still chokes up, almost 30 years later, when talking about Grant’s passing.) The Orion Duo recorded an album in 1981, The Orion Duo Performs. Benedetti recalls that he and Grant played two nights a week at the Prophet. Speaking of the duo Benedetti recalls: “That’s where I thought everything was going to go. We played together for many, many years. I invested everything in that classical guitar duo. I put away the steel strings. At the same time I transferred over to San Diego State and was getting my degree there. All of what I was doing professionally was to try to promote that duo. I wasn’t doing anything other than that duo.” Benedetti and Grant practiced together three to four hours a day. “The whole focus of the duo thing was about getting better as a classical player.” Together, they perfected their craft as guitarists. Grant’s untimely demise was devastating to Benedetti. Many musicians would have become de-railed by such a traumatic event. Instead, it became a turning point for Benedetti. Grant’s death led Benedetti to move in different musical directions. He ceased playing classical guitar exclusively and broadened his repertoire to include other genres. He had to; there simply weren’t that many options for a solo classical guitar player.

But Benedetti’s musical discipline didn’t waver. The Segovia competition came just two years after Grant’s passing. Initially, Benedetti thought auditioning would be a waste of time. How could he possibly hope to be selected for such a competitive and sought-after class? He recalls, “I thought, why should I even try?” However, a friend urged him to apply. “I put a tape together and mailed it on the last possible day, never thinking I would get in. About two weeks later I got a letter that said thank you for your application, but you haven’t been chosen. And then that afternoon, I got a call and was told that the letter was sent to the wrong person. You’re in. You’re Fred Benedetti? You are one of the 12 people selected for the master class.” He was shocked. In tribute to the memory of Grant, his beloved friend and musical partner, Benedetti performed before Segovia (his father’s idol, with his father proudly watching in the audience) using Grant’s footstool (which he continues to use to this day). Benedetti says, “I know Dan would have gotten in the class. It was my way of having him there too, to share the moment. He was a big reason that I was selected. That was important to me, to have that stand there with me.” Another turning point.

In 1985, Benedetti was offered a part-time position teaching guitar at Grossmont College, which he accepted. After the Segovia class, a full-time position opened up at Grossmont College for a “concert band” teacher. The department chair encouraged Benedetti to apply, but Benedetti resisted. “I didn’t feel qualified. I had played in concert band in high school, but I’m not a concert band person. The chairman convinced me that full-time positions don’t come around very often, and that once I got in I could restructure it to teach more guitar classes.” He decided to give it a shot, but the audition process required him to perform a concert band instrument. Benedetti dusted off his saxophone , which he hadn’t played since high school, more than a decade earlier. “I learned a couple of pieces of Bach, went in there and auditioned, playing the saxophone and the guitar. I did a teaching demonstration. And it was down to two people. I saw who my competition was— a conductor. I thought, ‘Ain’t going to get that. Ain’t going to happen.’ And then they did the final interviews with the president, and I got the call. The chairman said, ‘Congratulations, you got the job. They want you.’” Just like with the Segovia competition, Benedetti wasn’t expecting to be chosen. And here it is, 26 years later and Benedetti is still teaching full time at Grossmont College (although not, thankfully, concert band!). It would have been easy to give up and not apply. It is hard to imagine the pluck it required for a classical guitar specialist to audition for a band job playing the saxophone, competing against a conductor. But he got the job “I’ve been doing it ever since.” Another turning point.

Since 1986, Benedetti’s musical career has been a blur. He teaches full time, plays in numerous ensembles, spent 15 years doing session work at Studio West and Signature Sound, and recorded dozens of albums and CDs. He plays almost every night at churches, hotels, restaurants, even airports. In the summer, he and George Svoboda (whom he regards as a brother) perform throughout Europe (especially Svoboda’s home in the Czech Republic ). How does Benedetti maintain this dizzying schedule (a question frequently posed by his students)? He responds, “I get energized by playing. It is not work to me. I enjoy it so much. I never get tired of it. I feel fortunate that I have been able to do only music as a vocation.”

Fast forward to 2006. Benedetti had been performing solo classical guitar in the lounge at the Four Seasons in Carlsbad for about 10 years. It was a great gig — three nights a week at a five-star resort, with an annual contract. The staff and guests were unfailingly gracious. And since it started, Benedetti had not even had to compete for the renewal, despite regular turnover of management personnel at the resort. The extra money he earned moonlighting had allowed his wife, Amy, to be a stay-at-home mom to his two daughters. Benedetti could hardly believe his good fortune. Then, as his annual contract was coming up for renewal, the new lobby manager asked the question he had been dreading: “Do you know anyone who sings?” Benedetti is strictly an instrumental performer, and his repertoire did not include a vocalist. But after a decade of Benedetti’s solo playing, the Four Seasons management wanted to have a different sound. Benedetti was flummoxed. He impulsively responded, “I don’t sing, but my daughters do.” The manager invited them to audition, along with other combos that included a vocalist.

When Benedetti got home, he asked his daughters, then 15 and 18, if they would be interested in performing with their father at the Four Seasons. They thought it was a joke. They had sung in musical theatre, but never with their father in front of a crowd. Still, with their father’s can-do attitude, Regina and Julia practiced some numbers and gamely auditioned (with their father playing guitar) in front of the entire hotel management team while the other competitors watched. It was a nerve-wracking experience for the girls, although they remained poised (even as their hands were shaking). Their father’s long-time gig was on the line. The newly minted Benedetti Trio wowed the management and got the job. For the next four years, Benedetti’s daughters performed with him two nights a week, and he continued to perform solo one night a week. The Benedetti Trio still performs regularly every Thursday from 7-11 p.m. at the Grand Del Mar. Another turning point.

The music business has changed since Benedetti started teaching. CD sales are down. Session work is harder to come by. Opportunities are more limited. Challenges abound. What does Benedetti tell his students? His advice is predictably upbeat: “There are no guarantees in this business. Be very versatile. We are working musicians. We have to play a lot to make a living. Don’t give up. Look at every challenge as an opportunity.” Benedetti’s own career is a case in point.

Besides his weekly gigs, you can see Benedetti perform with Peter Sprague as part of the San Diego Folk Heritage Concert Series on May 5 at the San Dieguito United Methodist Church in Encinitas. He will also be at Ki’s Restaurant in Cardiff, along with his daughters on Saturday, May 12. Find out more at www.fredbenedetti.com