Cover Story

Jeff Berkley: Chance, Intention, and the Wave of a Magic Wand

The inimitable Jeff Berkley. Photo by Thom Wollenweider.

Having been assigned the task of writing my first cover story about a topic so long-standing and deep was excitingly daunting, and it was an interview I was looking forward to. I sat down with Jeff Berkley on a hump day, late in September, darn giddy about the prospect of learning more about this guy than I’d ever hoped. I studied previous articles about him so as not to cover the same stories; I was in search of current and new revelations about his life and career. He had declared no subject off limits, so I had spent a good while preparing all those possibly invasive and provocative questions. Anything I had ever wondered about went on the list. And then, even more. I have a collection of my own standard questions I draw from to get to know each musician I interview. They happen to be the same questions I ask myself. Little by little, I’m answering them too.

And now, it’s on to the man of the hour.

17-year-old Berkley on drums.

His current onstage incarnations include leading the all-star Jeff Berkley and the Banned, performing with Calman Hart as half of their duo Berkley Hart, and with a new solo album due to release next year, Berkley’s been doing a lot more solo shows and touring. Each of these is rewarding in different ways. When playing with others, there’s the collaborating and the constant reaching out and receiving, the back and forth, which is beautiful in its own way. About solo work, he says, “When you’re alone on stage, all of that falls away for better or worse, and you’re completely intact. And all the moves that you make with the audience are immediate; you don’t have to keep anybody with you. You don’t have to bring anybody along; you don’t have to make sure that everybody’s on the same page and moving as one living organism. It’s really freeing as a solo artist to just be up there and deciding what you want to do. I don’t make set lists when I’m solo. I just decide what’s next based on what the audience is giving me back and I love that.”

Pushing that solo envelope even further, Berkley had assistant engineer Amelia Sarkisian set everything up at Satellite Recording Studio and left him locked in the studio by himself for four days to record his upcoming album Tumbleweed. He pushed record and let it roll. Without using headphones, he recorded all the vocals and guitars at the same time using room mics. That meant that the sound from the amp sitting five feet in front of him bled into the microphone he was singing into. And it also meant that without the ability to separate instruments from voice, there would be no tuning anywhere on the record. He later added bass and drums to two of the songs and overdubbed harmonies here and there. Every bit of the album is him, just this guy sitting alone in a room playing his wooden instruments and singing—wholly organic, no tricks, exploring the rawness. He had never done an album in this way and reveals, “It’s just me, that’s all you’re going to hear, and that’s terrifying.”

Ben Moore, Berkley, Nucci Cantrell, Clark Stacer, Calman Hart, 2001.

Terrifying or not, Berkley keeps going. In one form or another, and in every aspect of his life, he is immersed in music, fully submerged and soaked to the bone. From the beginning, there were signs that the path chose him and that he fell willingly under its spell.

From playing drums on cardboard boxes at two years old to real ones at 10 with his dad in the church band, Berkley was a natural percussionist. His drive led him to join the junior high school drum section and concert band at 12, where he learned to read music and study rhythm. At 14, he joined his first rock ‘n’ roll band and met his friend Mark Tiesen, who would become a huge influence on Berkley’s understanding of music writing and performing. Just one year older than Berkley, Tiesen had already been writing songs on guitar and piano, and soon they were writing songs together. Berkley remembers, “He was, to this day, the best songwriter I’ve ever known. We do a song called “Envy Things” with the band.” Their partnership was profound and saw them skipping school to work on music, to listen, and explore. Cigarettes, girls, and drugs were part of their adventures and exploration.

I’m not letting any cat out of the bag when I say that marijuana is one drug that still plays a big role in his life and music. Tongue in cheek, Berkley says, “Oh yeah, I’m stoned only when I’m awake.” He was in high school in Vista when it was known as the meth capital of the world. The drug was everywhere, free pounds of it. Because he’d been told that all drugs were bad, he thought they were all the same. But after trying marijuana and finding out he’d been lied to, he figured they must have lied to him about everything and set about trying them all. He and Tiesen did a lot of speed, cocaine, and acid, and then in order to go to sleep, he’d get stoned. His current relationship with marijuana is beneficial and I admire how open he is about his use. He says, “Marijuana has just been a companion piece for me. It’s been something that pulls me out of my loops. When my brain is out to get me, marijuana actually pulls me out of that enough for me to cope. It allows magic to creep in when maybe I’m too tired for it. That thing of short-term memory loss is also short-term pain loss. You forget the shit you were pissed about yesterday. That is so good for me, and I’ll live with the other short-term memory loss stuff for that one thing. I just don’t have institutional memory of pain like I used to, and I love that. That doesn’t mean I’m ignoring it, it’s just that I’m not dwelling on it constantly. I’m working on it but not dwelling on it.”

Mark Tiesen

Still, that pain almost killed him multiple times. Tiesen, the most important person in Berkley’s young life, passed away at 20 from a heart murmur and the effects of all the drugs they were doing. Tiesen had been everything to him, everything. He spent the next few years in darkness. Knowing that meth had killed his best friend, he knew he would have to quit. But before doing that, he binged on it, and spent many a night sitting in the Tri-City Hospital emergency room parking lot, trying to talk himself into going in because he knew he was probably going to die, but then he just kept living. That darkness was ever present for a good many years in which he admits he was not a nice person. “I was an absolute womanizer and taking advantage of people and not being okay with people’s hearts and just all of the things that are horrible, and I was bringing all that negativity on myself and none of it got better until I stopped doing that shit; I lost my marriage, and I almost lost my kid.”

Because of mistakes his ex-wife made, Berkley got custody of his daughter. Raising her and music brought him out of the darkness. Getting to go on the road with others and his own bands pulled him up and got him off all those drugs. But he decided that “weed was probably the only one that helped. That was a tough time, but I think we all kind of go through a separation, you know, where our rocket sections fall away. And eventually we’re just burning clean, but it takes a while.” Burning clean indeed.

Growing up the son of a world-renowned evangelist, it’s only fitting that Berkley would want to move people’s souls. Music has that potential, yet he knows money gets in the way. Once money becomes the motivation behind it, the purpose gets twisted and “if you’re doing that, you’ve already lost.”

Solo Jeff

His recent tour brought that more into focus for him. “The way you make money is to move people’s souls, and the soul will reach into that person’s pocket and give you money without even thinking.” His main objective during the tour was to do better everyday at connecting with people in such a way that “everything else in their life falls away and all they are—in that moment—is with you and you’re enriching them in some way with whatever that thing is that comes through us when we play, which has nothing to do with us. Stay out of the way of it and let it happen and watch it happen. That was my whole goal of this tour; all I was doing was reaching out with my heart.” He continues, “That’s how we’re going to get people on our side. I don’t know any other way to do it. The audience wants to relate to what you’re going through in your life and what they’re going through in their lives and how this song speaks to that, and how we can all dwell in it for a minute—maybe not solve anything, but we can all feel it together, right? When that happens to people, they go away, saying, ‘I want to feel that again,’ and they’ll come back and see you. Having to use something so spiritual to create revenue is a real mindfuck.”

Berkley has found a multitude of ways of making a living through music. Having never been in the box, thinking outside of it seems to come easy to him, he’s constantly expanding his process and rediscovering who he is and what he can contribute. His purpose and reason for doing what he does has changed dramatically over the years, he shares, “I was just like anybody else at first, it was just, you know, to meet girls when I first started; I’m just going to be perfectly honest.” He can only speak for himself but he knows that he spent a lot of time with the attitude of wanting to get more, be bigger, be the best, and says that “over the years, that stuff’s falling away. And it’s really just become about connecting and living each moment because there really is no future, no past, they don’t exist at all. All we have is right now, so that really has changed the meaning of why I do it. I feel happier about my motivation now than ever.”

Jack Tempchin and Jeff Berkley jam at a Troubadour Holiday Part, ca. 2010. Photo by Dennis Andersen.

He feels more like a success than ever, too, but not in the way he thought it would be. “I’ve had some times where I flew pretty close to the sun. As a percussionist, I got to play with big rock stars, and I had moments in front of tens of thousands of people. I’ve toured in buses and done all those things that I wanted to do and scratched all that stuff off the bucket list. I’ve won all sorts of awards and all those things that you can point to, but I’ve never become a rock star or become a millionaire or anything like that. I make my living as a musician. I make enough money to pay my bills. I don’t know how much more of a success you can be in the music business at this moment in history.” Closer to his heart, he shares, “I have an amazing daughter and she’s healthy and sure of herself and strong and that’s the biggest success in my life. I can’t imagine any other thing that makes me feel more proud than to just be able to talk to Dakota. And now I have a bonus daughter, Amelia, and I’m so proud of her, too—I get to watch her success every day and it’s an amazing thing.”

Berkley, alone on stage, is easy. Nothing about him has any sharp corners. His mannerisms are gentle and deep, his voice rumbles steadily like the road under wheels; it’s welcoming and comforting. He’s quick to smile or even laugh at his own jokes; the two about cellophane and moths are my favorites, and I’ve told them countless times myself. Berkley is genuinely off the cuff and I wonder at how easily he talks and tells his stories. He’s honest—you just get that from him and from his lyrics. From Whore House, Hot Sauce & Souvenirs: Something ‘bout this moment makes me smile. Something ‘bout this time together, though it’s just a while. But I will carry all your hearts with me down each and every mile. Something ‘bout this moment makes me smile. That speaks to his philosophy and his way of looking at things. Then, there’s this one he wrote for his daughter, from the same album: The moon goes up, two hemispheres, same light there is glowing here. ‘Neath the hunter’s guide, I’ll meet you there, not so alone, not so scared. So, dial me up and tune me in, and I’ll be back home again, no matter where I’m bound. Oh, that melody is so sweet it carries me and brings me to tears.

Jeff Berkley and Sara Petite.

He is without a doubt my favorite guitar player. His fingers move like feathers over the fretboard, flowing effortlessly, and there are so gosh-darned many notes. Just when I think he’s run out of space, he adds even more and then it just keeps cascading until finally arriving purposefully on the downbeat. How does he do it? After one such demonstration at a Songwriter Sanctuary show in January, there was an audible gasp from the audience, to which Berkley said, giggling, “I know, right?” as though he even astonishes himself. This is kind of the magic wand part—his earnest boyishness is infectious and compels me to watch and listen, spellbound.

One of my favorite songs is one he does with the Banned. When they perform “Love” live, they play an extended intro and although it’s always different, I somehow know what it is from the first note. That may be intentional or it may be wishful thinking on my part, because I’m always on the edge of my seat waiting for it. It’s always dreamy and ethereal; everyone is in that groove, and then it builds until Well, it’s all gone to hell in a basket. Love is a spell, you can cast it. Just say the words, your heart knows the magic. If you ain’t sure, you can ask it. There’s lights and there’s smoke, and it’s all so beautiful.

Jeff Berkley joins Tim Flannery for his annual holiday show aboard the Star of India. Photo by Dennis Andersen.

Like so many artists, the thing that holds Berkley back is his own brain. On stage recently he found himself worrying about ego stuff, “How do I look, is my hair too frizzy or whatever, like stupid shit. It’s hilarious. It’s the stupidest thing that we would think about when we’re on stage. So, I’m up there and that’s what gets in my way, honest; it’s that impostor syndrome thing. That thing of what am I even doing here? Everyone knows I’m a fake. They’re all gonna figure it out, and they’re all gonna know, and you’re laughing because it’s so weird.” Yeah, I admit to him that I do know all about it. He continues, “It really is me and my own insecurities that are from whatever in my past when I was a kid, because my daddy didn’t pick me up on time sometime or whatever.”

There’s looking back, and there’s therapy, and Berkley is done analyzing himself, sick of hearing the sound of his own voice talking about his own problems. His theory, “I think therapy is literally just a place for us to speak out loud so that we hear ourselves and go, what the fuck. I need to let this go. I can get in my own way so easy and I do it every day in every little thing. And I literally have had to put mechanisms, coping filtering mechanisms in place to ignore that asshole because he is out to get me. He’s going to try and kill me. If I listen to that guy, it will not take me down a good path. Also, that guy’s really good at art, so I can’t kill him, but I really hate that guy.”

Right about then, we come to an agreement that even with all the negative self-talk and self-doubt, the drive to do music is even greater. It means we can’t not do it. It makes us who we are, it’s obligatory, it’s breathing, it’s drinking water. But it hasn’t been without sacrifice, both for himself and for family and friends. He shares, “My kid, growing up, didn’t want me to be gone four nights a week and all day long in the studio. That’s what happened. And it was hard. It’s hard for anyone to understand that doesn’t have the drive, the thing in us that makes us have to do this. And it’s hard to remember that when you’re in it and have to do it. It’s the most important thing at that moment for you, and they hate that and I don’t blame them.”

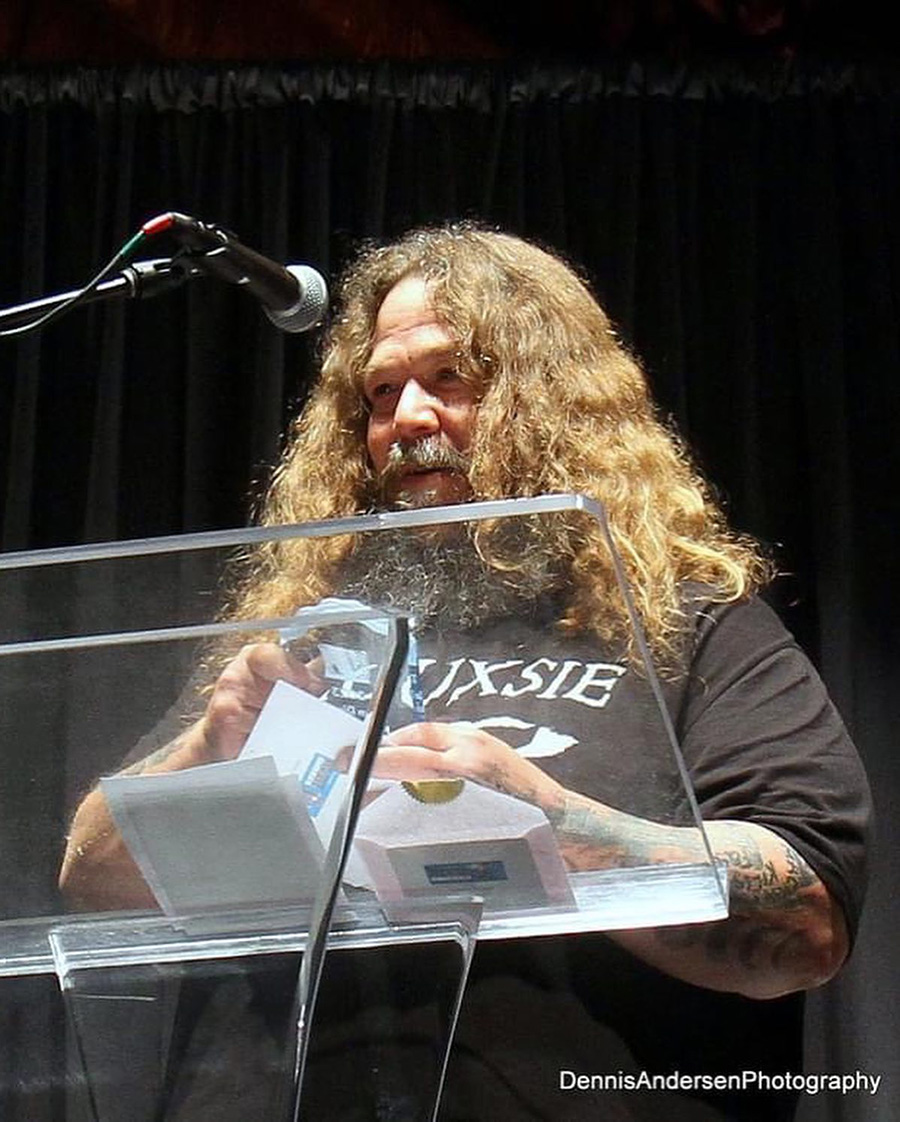

Berkley receiving the award for Artist of the Year at the SDMA. Photo by Dennis Andersen.

This year has seen some coming-to-fruition moments, beginning with winning Artist of the Year at the San Diego Music Awards. I was there to witness it, and somehow felt almost as proud of him as though I’d won it myself. There’s something about him that draws me in to his warmth and makes me feel as though I’m a part of his momentum, part of his effort, and part of his belief in music as a unifying force.

Winning such an award humbles him. “I’m very, very blessed by the San Diego Music Awards. Somebody did a count and Berkley Hart have won 12; as a producer I have been a part of probably 30 or 40 albums over the years. I won two this year. One was for Americana Album of the Year for Jeff Berkley and the Banned, and that’s for all of us. But I also won Artist of the Year personally. And that I think that has just as much to do with is me as a producer and just sort of a guy, a networking guy in town trying to make something happen here. You know, all of that stuff.” I guess I’m bragging but I am also really honored!” He sure as hell should be bragging.

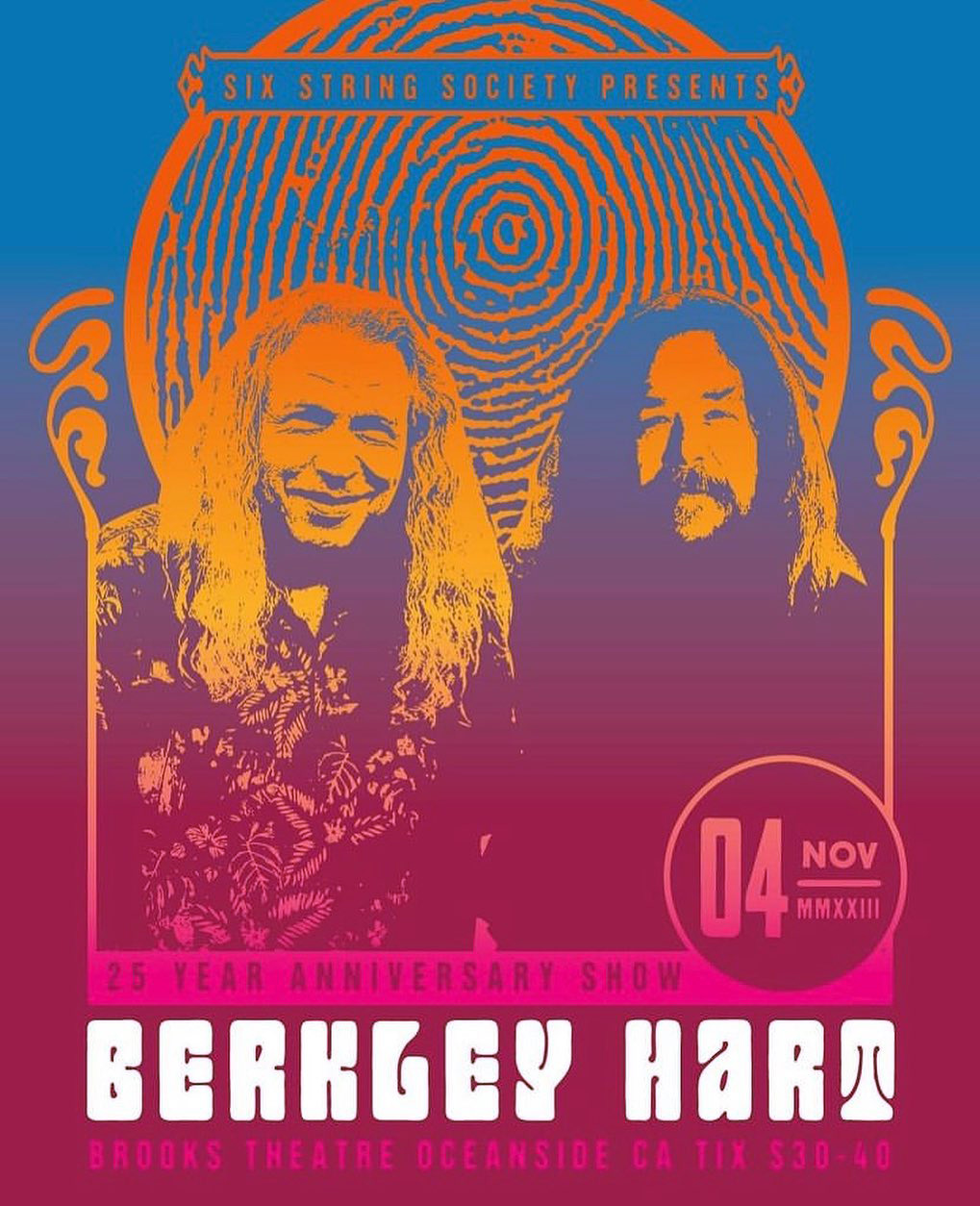

Berkley Hart poster for the 25th anniversary show on November 3.

Next up, on Friday, November 3, we will see Berkley inducted into the San Diego Music Hall of Fame, taking place at Vision: A Center for Spiritual Living in San Diego. When it was announced, he was completely taken aback and admits to having cried like a baby. Along with that imposter syndrome comes the disbelief. “I don’t know about you, but we don’t look at ourselves like that. We don’t even think we’re supposed to be here. I don’t even know how to handle the stuff, but I will take it and and say thank you. And I have worked my ass off and everyone around me has sacrificed so much. My exes, God bless them, and my mother and my daughters. Everybody who has ever been anywhere near me personally has had to sacrifice everything. I play gigs every day. I’m out late at night, my schedule’s weird. I’m moody, I’m a freak. I went through long periods of time where I didn’t make any money at all, and the people around me just supported me. Their lives are in there somewhere, but that Hall of Fame thing just makes me think of all of them and thank God that I have something I can point to and say to them, ‘Thank you for all that sacrifice.’”

While I’m talking about dates and special happenings, I have to point out that on November 4, the multi-award-winning Berkley Hart will celebrate their 25th anniversary with a show at the Sunshine Brooks Theater in Oceanside. They’ve come a long way from that meeting at Java Joe’s, when Calman Hart told him he wouldn’t need him to sit in on percussion for his song.

Looks like I’m going to have to backtrack now and talk about those influential and groundbreaking days at Java Joe’s. Berkley and John Katchur started a series there on Tuesday nights called the One-Shot Showcase, where 25 or 30 singer-songwriters would come and do one song each and the audience got an incredible show. Berkley would stand on stage with his djembe, ready to sit in with any of them. When Hart declined his offer, Berkley was offended and huffed off the stage only to stand by watching with his arms crossed. Later that night, however, he and his ex couldn’t stop talking about Hart’s song “Barrel of Rain” and respect for Hart’s songwriting blossomed.As he was learning to play drums for so many songwriters, Berkley was also crawling inside those songs and learning how to write for himself. He met folk singer Joel Raphael at one of the showcases and started playing and touring with him. When Joel won the Kerrville New Folk Award in 1995, they started performing in folk festivals and caught the ear of Jackson Browne, who signed them to his label. That opened a big door for Berkley, and he began playing percussion for Browne, David Crosby, Ben Harper, and the Indigo Girls. All that time, he was writing songs but not playing them for anyone.

When he wrote “High School Town” he played it for Hart. Berkley remembers, “At that point, I would just back him up on his solo shows. But he was the only guy that would actually say, ‘I’m going to leave the stage and have my drummer do a song’ and hand me his guitar and leave. He’d sit down and order a coffee and say, ‘Do another one.’ I’d never had anybody do that before. I’d never had anybody be so sure of themself to not be threatened by that. I mean, the easiest way to get fired in a band as a drummer is to show up and go, ‘Hey guys, I have a song.’” He continues, “So Calman was so supportive and he was like, dude, you should enter Kerrville. I was like, okay, so on the very last day I did; I had already been there several times and had played with a bunch of people. They knew me but when you enter, they take your name off it and give you a number, so they don’t know who you are. I got chosen as a finalist and went and I won. And my judges were Lucinda Williams, Amelia Spicer, and this guy that wrote songs with John Prine and Eric Taylor. It was the most amazing time in my life.” After that, everyone wanted him to come play and Berkley didn’t have any idea how to handle it. So, in 1999, he and Calman started Berkley Hart. They recorded their album Wreck and Sow and it won five San Diego Music Awards that year, and Hart won Best New Artist for the second time in his life, 20 years after the first time.

Berkley’s award-winning song, “High School Town.”

Berkley says fondly, “So, that was how Berkley Hart started and we’ve just never had a bad day. The way our voices fit is completely accidental. It’s not trying. It works. It’s always fun. We don’t fight—we’ve had little bumps but nothing like you hear about. So, still to this day even though he doesn’t really want to travel anymore, neither of us would ever not want to do Berkley Hart anymore. It’s so rewarding, and it’s such a blast.”

Back to the now, I asked him what he’d like to change about the industry. He mused, “What if it really was just about the kind of goodness you generate as a person and artist. That is a pipe dream; it’s never going to happen, because somebody has to be in charge of making decisions on where the funding goes and who becomes successful. But so often big successes in the music business are not about the music in any way and if it was up to me, I would take that aspect out of it and just have it be about how much magic are you producing and how do you make people feel when they leave?

Jeff and his daughter, Dakota.

“How are you helping each other be happy and move forward in a positive way? That’s a lot to ask for music but I think that’s got to be what the business is based on and if those became priorities again, I think people would remember why music fed their souls and what they’ve been missing when they don’t listen to music anymore and when they devalue music. Our culture has completely turned its back on art and says it really doesn’t mean anything at all; the mainstream culture has really done that. And so, I would change that if I could. I’m going to just keep moving forward as positively as I can and in the folk world luckily, it’s still about the things I’m talking about and I love that. I’m going to continue going down that acoustic, Americana rootsy road because that’s the place for me.”

Finally, when I asked him if he dreams big, he had a different take on it. “I’m trying to visualize how great it could be in whatever way it wants to be. My dreams have become more of me trying to just put things in motion, like get my synapses popping in the right direction. So, the electricity coming from my brain is entering the universe electricity field and putting that energy out there, literally putting positive energy out from the synapses in my brain because those are all little electrical explosions, you know, and in between me and you are nothing but electrical particles. So why wouldn’t that affect things? I don’t know; maybe I’m wrong, but it’s a good way to look at it.” Yes, it’s a damn good way to look at it.