Yesterday And Today

This Is the Day: Breaking Out of Obscurity with the Inmates

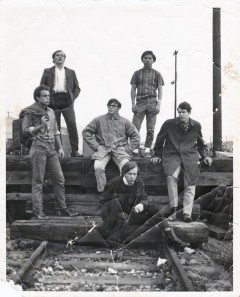

The Inmates, circa 1966. Left to right: John Poppe, Steve Phillips, Gale Kellogg, Jim Conder, Lloyd (Kenji) Kozuma, Tom Kruse. Photo by Cecil Caulfield.

Have you heard the one about the garage band from Ocean Beach, California, who, after making one obscure 45 rpm record in 1966, disappeared off the face of the Earth, with their singular piece of plastic destined to become a prized collector’s item, fetching hundreds of English pounds amongst the Northern Soul cognoscenti in Britain? No? Then it’s high time to get hip to the Inmates, one of the great, lost bands of San Diego music lore.

The Roman candle trajectory of the Inmates is a classic American tale, paralleling thousands of fellow aspirants across the trashed-out teenscape of the post-apocalyptic early 1960s. After a futuristic-looking quartet from Liverpool, England, magically shifted the cultural paradigm overnight via mass televisual hypnosis, the resultant aftermath touched off the seismic perception that any four guys could stand on stage, make their own kind of rhythmic racket, shake their heads and hips in unison, and the girls would summarily fall at their feet. From San Bernardino to Boston, a significant number of baby boomers, overwhelmed by their suddenly surging hormones, flashed on the notion of exploring their own creative potential–which was no doubt inspired by the phenom of witnessing 300 pubescent girls shrieking in unison.

The Beatles provided proof positive that it was cool to be in a gang. And during their leather-jacketed, pill-popping, drunken apprenticeship in Hamburg, Germany, they were as “punk rock” as anyone–before or since. But by 1964, the media passed the rebellious aroma of “bad boys supreme” onto the Rolling Stones, whose contrived menace embodied the ’tude of “punk” until the entire idea was co-opted into some bastardized, fascist marketing campaign. The Beatles and the Stones: two sides of the same coin, establishing the contextual benchmark of “cool” for the ages.

And, really, who among us doesn’t wish to strut their stuff and project an aura of “cool” to the world? Inspired by surf music, R&B, and the escalating wave of the British Invasion, a motley assortment of eighteen-year-olds, recently graduated from Point Loma High School, discovered exactly how cool it is to be in a band when they started informally jamming together. Their efforts eventually resulted in having their music played on the radio and performing to packed dance floors across San Diego County.

Gale Kellogg: “We were all surfers and that’s how I met [guitarist] Steve Phillips. He lived at the end of [4858] Pescadero Avenue, which was the surf spot down in O.B. I’ve always liked music and I wanted to play the drums, but my family couldn’t afford it.

“However, that all changed in June of ’64 when we hosted a big graduation party at my house [4352 Niagara Avenue].” When the Impalas were enlisted to provide entertainment, Kellogg suddenly found himself with a coveted set of skins. “After our graduation party, Scott Beamer left his drums in the garage. And me being me, I went out there and played ’em for about 12 hours a day.

“Whenever the surf wasn’t very good I would go down to Hazard Brick and Block in Mission Valley [now Hazard Construction Company] and work as a yard boy loading cement bags and blocks for a buck and a quarter an hour, which was good money, and that enabled me to rent a set of drums at Dave’s Music on Fifth Avenue.” Almost immediately, Kellogg began performing with some of his neighborhood pals: lead guitarist and background vocalist Steve Phillips, bassist Tom Kruse, rhythm guitarist John Poppe, and saxophonist Lloyd (Kenji) Kozuma.

It’s all in the proximity

Tom Kruse: “The Inmates evolved from parties around O.B. where a few of us were learning to play guitar. I lived across the street from Gale and he had a garage that he converted into his bedroom and a general hangout place for friends. We learned a lot about booze and girls there. The Kelloggs also had another garage in the back that we used for practice. My stepfather often called the police to complain about the noise: especially the bass. He was an asshole.”

Steve Phillips: “Gale’s mother would bring us beer when we practiced. We loved Ma Kellogg, as if she were our own mother. Her rules were: as long as you’re in the back yard in the garage you can drink the beer–you’re not taking it with you. And if you’re too drunk to drive you sleep on the couch. And she’d set us up with cold ones.

“As we started getting better, the next thing you know we were hiring out. San Diego was a much smaller place in those days. This was before drugs, with everyone just having a great time naturally. In the early days at least one fight would break out at every gig. But a guy didn’t go out to his car, grab a gun, and kill somebody.

“Remember, this was the leading edge of the baby boom, so there were a lot of kids, and they all loved music. We were playing for enormous audiences, and getting paid very well: 350 to 500 dollars for a three-to-four hour dance gig–in 1965—66 money.”

What’s in a name?

Kruse: “The fact that many of the guys in the band had been detained at one point or another by the local police led to the name the Inmates. To the best of my knowledge no one had ever served time. But in those days, that would have been a badge of honor.

“We started off playing instrumentals like ‘Perfidia’ and ‘Wipe Out,’ since none of us could sing. Lloyd’s younger sister Gerry sang a few slow numbers like ‘Angel Baby’ for us, but that was about it. But we finally found a full-time lead singer in Jim Conder [Point Loma High School, class of ’63], which enabled us to expand our song list. We played a lot of Rolling Stones (but not Beatles) songs. Jim considered himself the reincarnation of Mick Jagger–even down to copying his mannerisms.”

Phillips: “Oh, I really loved the Beatles, but to us they were kind of a candy pop group. We were huge Stones fans and we were more like them. We were grubby-counterculture-street kids. The Beatles were clean, the vocals were pretty, their lyrics were outstanding and I loved them–I think we all loved them. But we never played their music. We were into a grittier sound.”

The Inmates land in Jail

After establishing themselves on the San Diego music scene for nearly a year, Phillips was approached by a young entrepreneur by the name of John Kopit. Kopit convinced the Inmates that he could take the band to a higher level of success and commenced with building a youth club in Encinitas, 25 miles to the north of San Diego.

Phillips: “Kopit sold himself to me–he was a very energetic businessman, a Jewish lad from St. Louis who had already established and lost a newspaper before he was 26.” The first thing Kopit did was rent a building next door to the La Paloma Theatre in Encinitas, where the Inmates were installed as the house band. In a punning masterstroke of branding, Kopit christened the place the Jail.

Phillips: “Since John lived in Del Mar, the location was convenient for him. He utilized our young backs to help build the Jail: in other words we were free labor. We tore out the counter, built a huge dance floor and a professional stage with the help of some craftsmen.” The finishing touch to the overall theme was to take faux-black wooden dowel bars and stick them in the windows: the perfect pleasure prison for teenagers.

“It was a youth club,” says Phillips. “No alcohol. Just food and soda pop: real wholesome. On opening night, you could see the lights going by on the 101, because the Interstate 5 hadn’t been built yet. We’re on the main route, the only route between San Diego and L.A. We’re sitting there looking outside and as the headlights went by we can see all these people gathering: there must have been 500 kids out there, going in both directions. The place reached the fire marshal’s limit and we had to cut ’em off.

“We lit off on our sets and we’re seeing a sea of heads dancing [laughs], with silhouettes in the window and an equal number of heads bopping up and down and dancing on the sidewalk. That attracted attention, and not good attention. Encinitas is kind of a hip place now. Back then it was a Cowtown, and the locals were frightened of us. But we just went ahead packing the place.”

When asked what the locals were so concerned about, Phillips lets out a deep sigh. “I think they were afraid that we were going to have sex with their daughters: which we certainly wanted to do. [laughs] And we were going to corrupt the kids, playing ‘the devil’s music.’

“When Elvis would come to town, all the local churches would have alternative events to keep the kids away from seeing him bring his ‘Black’ music and his thrusting hips to town–it was that kind of thing. It’s hard to believe that I’m old enough to remember that mentality. In fact, they were so eager to shut us down that one of the angles they came at us with was an old statute prohibiting Asians from participating in mass gatherings that had been on the books since the railroads had finished and North County was hit by a big influx of Chinese immigrants. And we had a Japanese sax player. This is how ugly it got. It was not the pretext for shutting us down, but it was mentioned. Unbelievable, huh?”

After three months of packing in the audiences and raising the ire of the local authorities, the doors to the Jail were suddenly slammed shut.

Phillips: “The last night the Jail was open we were there playing on stage and all of a sudden the whole stage goes dead: they had shut off the power. The doors fly open and in come the cops, putting everybody up against the wall. They ushered all the kids outside, all the patrons. They took us off stage and separated us, asking us questions about everything: ‘What drugs had we taken?’ ‘What type of stuff were we on?’ They didn’t have breathalyzers yet, but they were looking to see if maybe we were drunk, because we were all under 21. They didn’t arrest anybody, but they taped the door shut and closed the place down–the long story short is that Kopit lost the Jail. The locals were honest about it from the very start: the public sentiment was that we weren’t welcome in Encinitas. So we left.”

This Is the Day: enter June Jackson

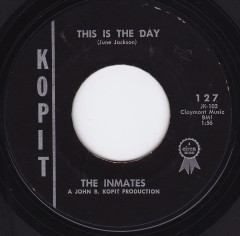

Phillips: “Somewhere along the line Kopit became convinced that we should make a record, because we were getting to be a pretty damn good band. But for some reason he decided it would be best not to record any of our original material–big mistake. We had a couple of originals, but Kopit hired songwriter June Jackson, who was out of the Motown school, and it was totally wrong for the Inmates.

“June insisted on bringing in his singers, Rita and Cathy, who called themselves the Crispy Twins. The three of them lived and performed together, which was unusual in those days, because June was Black and the girls were white. And I liked them as people; they were great, but the material was just totally wrong. Just the same, the record became very popular locally.”

In January of ’66 all six of the Inmates piled into Phillips’ Plymouth Valiant station wagon and headed north to Johnny Otis’ El Dorado Studios in Burbank to record two of Jackson’s compositions: “This Is the Day” and “Gypsy Heart.”

Phillips: “El Dorado was an enormous place–every instrument that you could think of was in this room. It took us a while to get the instrumental tracks down so that they were pretty much error-free. We were well rehearsed, but we had never worked with a sound engineer before, so he had to take 20—30 minutes with each person, getting their tone and levels–a lot of stuff before you even start tracking. We recorded on a two-track machine: first we recorded the instrumental tracks and then the vocals, all live in one take, mixed down to mono.”

In retrospect it is easy to understand how “This Is the Day” became a latter-day Northern Soul favorite: the record has an irresistible beat and grooves with the best of the dance floor favorites then coming out of Motown. But once the record was pressed up on the generic looking KOPIT label (which was distributed by CIRCA: the Consolidated International Record Company of America based out of Hollywood), the real challenge began of how to get their music played on the radio.

Phillips: “I didn’t know how the recording industry worked in those days, because it was very, very hard to get into the main markets. But we did get some airplay. One of the biggest kicks of my life was hearing that the record had cracked the Top 20 in Escondido. ‘And here kicking-ass again this week from San Diego, California: the Inmates!’ Some of the outlying stations would play the record in Oceanside, El Centro. We ended up with a following of like-minded people and having a little brush with fame. We signed autographs–I had girls coming up to me crying, offering me their skirts to sign. In El Centro we played a teen nightclub called Poncho’s. We were in the Top 10 out there and we were well known in that little community: Brawley, Calexico, El Centro. Once again, Blacks were not allowed in the club: they had to enjoy the music outside in a similar situation to the Jail. There’s just a sea of these kids pressed up against the stage, and it’s like ‘Wow, my little taste of what it’s like to be a star.’ But the big thing again was through the window, these silhouettes; I could see all these Black kids just rocking out on the sidewalk. [laughs] And there was no trouble at all, it was such a nice night, everybody was really cool.

“Nowadays, I’m so glad that we have those recordings, because otherwise we’d have nothing.”

I Ain’t A-Marching Anymore

After recording their debut single, the Inmates believed it was the beginning of a prolonged recording career. But all that changed on February 8, 1966, when Kellogg was absconded by the U.S. Army. “I was the first one to get drafted out of the band,” says Kellogg. “And Paul Bleifuss took my place [Point Loma High School, class of ’65]. Paul was an excellent drummer and actually became quite famous as an innovative drum maker.” Bliefuss had a distinguished career as an artisan before succumbing to cancer on September 5, 2007.

“There was all this talk about our ‘next record,’ that this was just the beginning for the Inmates,” says Phillips. “It turned out not to be the case, because we were decimated by the Vietnam draft.”

With a lack of proper career management and a series of bad breaks, the Inmates tale smacks of more than a passing resemblance to the film That Thing You Do. “Actually,” says Kruse, “I think the movie The Commitments is the best story of a band coming together, having a few brief moments of fame, and then falling apart. I see a lot of similarities with our band in it.”

Breaking up that old gang of mine

Phillips: “After the Inmates broke up we all went our separate ways and then came back and settled down after the war. I went to school and became an urban planner, engineer, and architect.” After a stint managing Jim Conder’s band, the Roosters, in the 1980s, Phillips picked the guitar back up and can be heard these days performing with his group the Pescadero Pickers.

After getting out of the army in ’68, Gale Kellogg spent several years gigging with bassist Greg Willis (Iron Butterfly, Glory) and guitarist Dave Dorn. After touring for almost a decade, including a stint backing up Al Wilson (“Show and Tell”), he found himself living on the street for 15 years. Eventually, he cleaned up his act and worked for a dozen years for the Veterans Administration until his retirement a few years ago. These days, Kellogg is back behind the drums and gigs several times a week. “Music is what I live for,” he says. “And that’s why I play every chance I get.”

Phillips: “I heard that Jim Conder died in Florida (on June 19, 2014) due to cirrhosis of the liver. And none of us know what became of John Poppe.”

As for the other Inmates, saxophonist Lloyd Kozuma still lives in San Diego after owning and operating a successful dental laboratory, until his retirement a decade ago. After finishing college and joining the Peace Corps, bassist Tom Kruse enjoyed a career at Reynolds Metals Company in Richmond, Virginia, until his early retirement in 2000. With all seven of their children grown, Kruse and his wife are traveling all over the world, currently residing in Bordeaux, France.

“My wife was doing some checking online,” writes Kruse via email. “Apparently this group of collectors in Northern England is still going strong and an original copy of “This Is the Day” by the Inmates can fetch very high prices. A few years ago I saw one cited on eBay for 1,500 English pounds! Another entry lists it for 400 pounds. I did get a thrill when my son found it on the Internet about three years ago, because I had told my kids about my band days and they didn’t believe me. So the hype is not fictional.

“Not bad for a garage band from O.B.”

The Inmates story is excerpted from Encyclopedia Walking Volume II: San Diego Serenade, the follow up to the award-winning Encyclopedia Walking: Pop Culture & the Alchemy of Rock ‘n’ Roll. Volume II will be available in early 2017.