Yesterday And Today

The Anthology of American Folk Music: Hanging Out in the Ozone with HARRY SMITH

PART TWO

If everybody were an artist, there wouldn’t be any wars.

– Harry Smith (1923—1991)

In the age of information, where knowledge is the key to living a conscious existence, there is certainly no bliss in choosing to remain ignorant about the world that we cohabit. And in a materialist-consumer society such as ours, it is an extremely thin line between being a collector of valuable artifacts and a hoarder. As a professional archivist with over 12,000 pieces of vinyl and digital media to responsibly maintain, I can certainly appreciate the difference between having a disciplined focus in a specific field of endeavor and falling into the psychological trap of becoming a hopeless obsessive-compulsive. Whatever follies the Internet has wrought upon us, never before have we had more facts and figures at our fingertips. However, the greatest danger regarding the over-saturation of meaningless information (disinformation?) is that it is now possible to view a million unique videos on the YouTube channel of your choice and still remain relatively clueless about the wider world around us: the World Wide Web as a potential Tower of Babel.

One of the largest obstacles to becoming aware about the true state of our culture lies in the fact that the underclass has been hoodwinked for centuries about how the United States of America is the land of the free and the home of the brave. Rather, we are a corporation of indentured servants where the ideological fantasy of “democracy” reigns supreme. Incredibly, America has never been a democracy in the true sense of the word, because in order to have a participatory democracy all members of a community/nation require unfettered access to the information and issues that effect us as a collective. A genuine democracy would have to be synonymous with a policy of full disclosure in all matters, both foreign and domestic.

Unfortunately, deception and secret societies are the jolly roger of the political and cultural pirates who created and control the U.S. of A. Our nation was allegedly founded upon the twin notions of inherent sovereignty and equality. But, without actually practicing those principles, our true situation is a republic ruled by an oligarchy in order to sustain the elite privilege of those who benefit from the practice of crony capitalism and the spoils of perpetual war. These are the very perversions that Woody Guthrie wrote and sang out against during the first half of the 20th century, and their relevance has only intensified in the interim.

Guthrie: “There’s several ways of saying what’s on your mind. And in states and counties where it ain’t healthy to speak your mind…folks have found other ways of getting the word around.

“One of the mainest ways is by singing. Drop the word ‘folk’ and just call it real old honest-to-God American singing. No matter who makes it up, no matter who sings it and who don’t, if it talks the lingo of the people, it’s a cinch to catch on, and will be sung here and yonder for a long time after you’ve cashed in your chips.

“If the fight gets hot, the songs get hotter. If the going gets tough, the songs get tougher.”

Yes, as through this world I’ve wandered

I’ve seen lots of funny men.

Some will rob you with a six-gun,

And some with a fountain pen.

Much like Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States, the hidden history of America can be found in some fairly obscure corners of our culture. And if you truly wish to understand how America came to be what she is, it is crucial to listen and absorb the lessons that are inherent within the Anthology of American Folk Music. For that we can thank the improbable alliance of Harry Smith and Moses Asch, president of Folkways Records.

***********

In last month’s edition of the Troubadour we explored the eccentric life and times of Harry Everett Smith, a 20th-century Kokopelli trickster if ever there was one. Delving in and through a smorgasbord of divination systems, and practicing his own peculiar form of magical manifestation, Smith slithered between the shadows and light of Jungian archetypes, proving to be one of the more enigmatic figures of western culture. Not to diminish his accomplishments as a filmmaker and painter (which are significant), but Smith’s importance as an archeological tastemaker and shaper of culture is verified by what he wrought through the curation of the Anthology.

John Fahey: “Had he never done anything with his life but the Anthology, Harry Smith would have still borne the mark of genius across his forehead. I’d match the Anthology up against any other single compendium of important information ever assembled. Dead Sea Scrolls? Nah. I’ll take the Anthology. Make no mistake: there was no ‘folk’ canon before Smith’s work. That he had compiled such a definitive document only became apparent much later, of course. We record-collecting types, sifting through many more records than he did, eventually reached the same conclusion: these were the true goods.”

It may be hyperbole of the highest order, but that’s the way it is when people talk about Harry Smith’s Anthology. Many other figures played a significant role in the folk revival of the ’50s and ’60s: John and Alan Lomax, Robert Winslow Gordon, Ralph Rinzler, and Izzy Young, to name a few. But you can rest assured that without the release of the Anthology of American Folk Music in 1952 by Folkway Records we wouldn’t have had the Kingston Trio, Dave Van Ronk, Joan Baez, Odetta, Bob Dylan, Phil Ochs, et al. Without the folk revival there would be no singer-songwriter movement of the 1970s, and most of what we think of as “Americana” is due to the range of music represented on the Anthology. How it came together is rather remarkable.

In 1950, Harry Smith came to New York City on a Guggenheim grant from the Pacific Northwest via the Bay Area of California in order to study the mysticism of the Kabbalah, the bohemia of the jazz world, make experimental films, and continue to explore the relationship of musical sounds to visual notation/representation. Smith spent five semesters studying anthropology at the University of Washington in Seattle and, while working for Boeing aircraft during the course of World War II, had become obsessed with what he termed “exotic sounding records.” He became determined to obtain as many pre—1940 race and hillbilly records as possible, going so far as to place advertisements in The Record Changer magazine. Due to a U.S. government campaign to collect laminated records to procure shellac for the war effort, many people were donating their old 78 rpm records for scrap. This meant that many of the records from the ’20s and ’30s that Smith was seeking were in danger of disappearing. The upside to the government’s shellac drive is that it brought many records out of storage, and thus made them more accessible. Within a few years, Smith had “rapidly amassed many thousands of records. It became like a problem…. They were so piled around that it was impossible. There was no way of listening to them all, but you didn’t want to skip anything that might be good. It was an obsessive, investigative hobby or something.”

When Smith relocated to New York City, he had all of his belongings shipped from the West Coast. When his grant money was gone, he was stuck with over 14,000 78s and incapable of making ends meet. Being forever resourceful (which often required lying, begging, borrowing, or outright stealing), Smith approached Moses Asch, the owner of Folkways Records, to see if he would like to buy Smith’s collection. Asch upped the ante during negotiations and proposed something even more daring: instead of buying his collection, why not compile the most interesting records out of the collection for historical posterity? The 331/3 rpm long-playing format had been recently introduced by Columbia in 1948, making it possible to listen to more than one song at a time without changing the record. The creative possibilities provided by this new audio canvas intrigued Smith, and he accepted Asch’s offer, which included his own private workspace at Folkways to curate the Anthology.

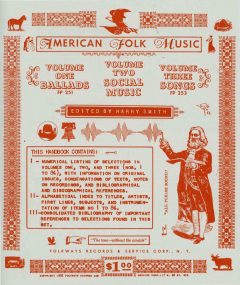

Harry Smith’s Anthology is not your run-of-the-mill compendium. He approached the project in the only manner befitting a visionary magician: as if it were a divination object in and of itself. He conceived of the Anthology as a four-part series containing two LPs each: with each volume color-coded to represent the four alchemical elements: green (water), red (fire), blue (air), and yellow (earth). Volume one was titled Ballads; volume two: Social Music; volume three: Songs. The fourth volume, titled Labor Songs, remained unreleased until 2000, when John Fahey’s Revenant Records finally released it as a two-CD box set. A fifth and sixth volume was proposed at the time, but never materialized.

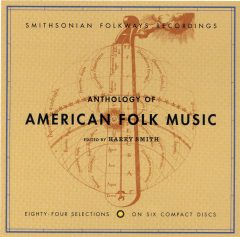

In addition to curating the songs, Smith also edited and art directed the design of the entire package, which included a 28-page booklet of liner notes, utilizing a collage method of visuals that draws upon record discographies from the ’20s and ’30s, with unusual clip art that looks positively post-modern. Each of the three double LPs carried the same cover image by Theodore de Bry, with an etching of an instrument “being played by the hand of God” referred to by Smith as the “Celestial Monochord.” Smith had incorporated both the music and the artwork into his own singular cosmology, and by doing so, changed the world of popular music in perpetuity.

***********

So what do we have when we explore the Anthology? The initial three-volumes released in 1952 contain a total of 84 performances, with seven songs per side of each LP, which tells a profound story about our collective ancestry. All of the recordings Smith drew upon were originally released as 78s, and recorded during the period of 1927 through 1932, before the economic devastation of the Great Depression eliminated the market for luxury items such as phonograph records.

Smith had his own peculiar logic as to why one particular song or artist was deserving of inclusion. I find the Anthology to be no less than a democratic rendering of what America truly represents, albeit through the sensibilities of the absolute monarch that is Harry Smith. These are the voices of the underclass: voices of the disembodied and the dispossessed, suggesting a sense of balance and fairness. You could even argue that the tone deaf and tuneless are given a fair shake as well in one or two of the selections.

Democracy as Smith perceived American folk music means the inclusion of black Baptist spirituals, white Cajun fiddlers, Appalachian claw hammer hillbillies, Chinese railroad workers, Mississippi shareholders, and the field hollers of ex-slaves. At times unintelligible, nonsensical, or downright inexplicable, the Anthology becomes a mirror of sociological and political import, begging the question: how do we successfully represent the broadest cross section of individuals within a particular culture? Is it even possible or desirable? It all comes down to what we value as a social organism. Democracy (and human nature) is a slippery devil, because in theory it means giving equal time to those who either haven’t got much to say, or to positively contribute to the discussion. If we insist on making sure that the world isn’t fair, what does that say about our collective lack of compassion for the inarticulate? Should those people be marginalized for the sin of not being born into privilege and being taught how to speak up eloquently and play the game with a vengeance? To quote Robbie Robertson: “Save your neck or save your brother’s. Look’s like it’s one or the other.” Harry Smith’s Anthology goes out on a spiritual limb and insinuates that there is room for everybody at the banquet table that we conceptually call “America.”

Diversity makes us strong, and inclusion is such a radical idea that it has the potential of wiping out the ignorance of dogmatic prejudice. Smith was too smart to make that sort of wry observation from a pulpit or a podium. But as an artist, he was able to make the point without being crucified for it.

Even if we’ve never worked in a field, attended church services, or drank illicit liquor from an old fruit jar, the culture of the 19th century lives and breathes in these performances. The Anthology of American Folk Music is a primer in simplicity and a timeless reminder of the joy to be found by living in harmony with nature and your neighbor. Conversely, there are a number of songs that serve as a cautionary tale about the hellish consequences that await those who are incapable of cooperation, compassion, and empathy. For example, by Fahey’s wry observance, over 15 million people perish over the course of the Anthology: “Twenty people are killed or commit suicide on the domestic scene, and 1,513 people died when the Titanic sank. If we add to that the 15 million people killed in WWI, an event mentioned by Blind Lemon Jefferson and Cannon’s Jug Stompers, we get a total 15,001,533 deceased.”

***********

There is something of a “museum” quality to these recordings, and I find it fascinating that we are able to listen to music that was performed and recorded nearly a century ago–it’s already been 65 years since the Anthology of American Folk Music was initially sent out into the world. In 1987, the Smithsonian Institute acquired Folkways Records from the estate of Moses Asch, with a back catalog of 2,200 titles that continues to inform and inspire current generations regarding our deep cultural heritage. In 1997, the Smithsonian reissued the Anthology as a six-CD box set, improving the sound quality of the 1952 release, and finally licensing the material in a proper manner that neither Smith nor Asch felt compelled to do at the time. The 68-page booklet that accompanies the music is a treasure trove of contextual information and analysis, rightfully proclaiming that the Anthology “stands on Harry Smith’s shoulders at the boundaries of science and art, history and aesthetics, scholarship and commerce.”

“Folk music,” of course, includes both traditional music and the genre that evolved during the 20th-century folk revival. The term originated in the 19th century, but often refers to music that is much older than that. Traditional folk music has been defined in several ways: as music transmitted orally, music with an unknown composer, or music performed by custom over a substantial period of time.

In 1968, Smith sat down and spoke with John Cohen of the New Lost City Ramblers for Sing Out! magazine (it is reprinted in the compendium Think of the Self Speaking). Cohen’s interview is one of the more valuable meditations regarding the Anthology.

Cohen: “The Anthology was the first opportunity many of us had to hear the country blues, early hillbilly, and Cajun music.

Smith: “The first time I heard Uncle Dave Macon was somebody playing old records in the basement of a house that had been converted into a funeral home in Seattle.

“The first record I bought was around 1940. It was a Tommy McClellan record that had somehow got into town by mistake. It sounded strange, so I looked for others and found Memphis Minnie. I started looking in other towns, and then I arranged for other people to look for old records. There was a book from the 1920s published by Howard University, where I first heard about Blind Lemon Jefferson and Blind Willie Johnson. I was looking for exotic records in relation to what was considered to be the world culture of high-class music.”

Cohen: “To my mind the Anthology anticipated the popular rock and roll music which followed. Many rock musicians are returning to those sounds. To me, today’s music seems like an extension of the Anthology.”

Smith: “That’s what I was trying to do, because I thought that is what this type of folk music would lead to. I felt social changes would result from it. I’d been reading from Plato’s Republic. He’s jabbering on about music: how you have to be careful about changing the music because it might upset or destroy the government. Everybody gets out of step. You are not to arbitrarily change it, because you may undermine the Empire State Building without knowing it. Of course, I thought it would do that. I thought it would develop into something more spectacular than it did, though. I had the feeling that the essence that was heard in those types of music would become something that was really large and fantastic. In a sense, it did in rock and roll. I imagined it having some kind of social force for good.

“The Anthology was not an attempt to get all the best records, because there are other collections where everything is supposed to be beautiful. But a lot of these were selected because they were odd–an important version of the song, or one which came from some particular place. For example, there were some things from Texas included that weren’t very good. There was a Child ballad, “Henry Lee” [Child 68]. It’s not a good record, but it was the lowest-numbered Child ballad. Then there were other things put in simply because they were good performances, like “Brilliancy Medley” occurs to me. You couldn’t get a representative cross section of music into such a small number of records. Instead, they were selected to be popular among musicologists, or possibly with people who would want to sing them and maybe improve the version. They were basically picked out from an epistemological, musicological selection of reasons.”

Cohen: “You once told me of your many new plans for volume four of the Anthology.”

Smith: “The real reason that it didn’t come out was that I didn’t have sufficient interest in it. I wanted to make more of a content analysis. I made phonetic transcriptions of all the words in the songs, but those notebooks got lost.”

***********

On any number of occasions Smith claimed to be an alchemist, practicing magical spells in the tradition of the Ordo Templi Orientis, eventually utilizing his artistic and divination skills to create his own personal Tarot deck. It is not a large leap to conceive of the Anthology as a form of divination art–a collage of found objects and symbols that when taken as a whole, synthesize into something much more profound than the sum of its parts. Carl Jung spoke of the collective consciousness as something akin to the Akashic records: where all that can be known by human beings is accessible through the proper stimulation. Bearing in mind the power of myth and the language of archetypes, divination systems such as the I Ching, astrology, the Pachakuti Peruvian Mesa, the Tarot, and the Kabbalah all serve as a gateway for the conscious mind to dialog with the unconscious mind: to discover that which is hidden through occult means. It is possible to consciously choose from the entire range of all human probabilities and integrate those elements into a well-balanced and harmonious ego, if those are the values one has developed over space and time. Yin/Yang, the unified field, duality, freewill, karma: they all have a say in the dance that we conceive of as the third dimension…and beyond. Divination systems can be empowering, and serve to dissolve dogmatic, fundamentalist beliefs.

Mary Hill: “What did you learn about the Kabbalah?”

Smith: “Certain things, but I’m tired of that because there’s no real reason to do anything but trust in God. I mean, at this point I trust in God to direct my footsteps.”

***********

In the booklet accompanying the 1997 box set, there are several essays that expound upon the significance of the Anthology. But none of them are as entertaining as the unorthodox manifesto to be found on the late John Fahey’s website titled The Nature of Reality, which declares the Anthology of American Folk Music to be nothing less than a “religion.” This is the sort of passion you would expect from a musician and musicologist that made sure that Harry Smith’s fourth volume of the Anthology finally made it’s way into the hands of the general public. Harry Smith didn’t live to see it, but I’m grateful that his vision for the fourth element in the series was finally realized, albeit 48 years later.

Of even greater interest is Fahey’s demolition of Greil Marcus’ over-hyped tome Invisible Republic, and Marcus’ essay regarding the Anthology titled “The Old, Weird America.” Central to Marcus’ conceits and projections is his invention of a place called “Smithville,” a conceptual hamlet where each of the personalities found within the Anthology hang out together for all eternity.

Fahey: “Marcus wants us to believe that everybody on the Anthology has a homogenous, or perhaps even an identical Weltanschauung. He wants us to believe that all Smithvilleites live and think and believe independently of the prevailing Weltanschauung and the Zeitgeist. Not only that, but he wants us to believe that they do this deliberately, on purpose, and by preference.

“Ah yes, dear old Smithville, deep sunny south by the sea, you turn around and in the distance you can see the beautiful mountains of self-deception, crowned with the snow of ignorance.

“I hereby declare the Invisible Republic to be a frighteningly visible and gigantic insane asylum, disguised as a city-state, consisting of streets that go around and around and around and around in circles and lead nowhere, avenues which are dead ends, roads sided by false facades of buildings which are nothing but different wards for various types of diseased minds, sidewalks which lead to a gigantic maze, from which there is no exit, no escape. And, finally, people milling about in great confusion and perplexity, all of whom have been decided by the DIRECTOR as to their own identity and their own experience. The director himself is insane. The director’s name is Greil Marcus.”

***********

Like all art, music is a reflection of the consciousness of the people who create it. When those impressions are laid down they are either ignored and recede back into the void, or they are magnified and resound across the life stream, to assist in the seeding of new culture and awareness, which is, of course, a mutation of whatever preceded it.

We can see that mutation of cause and effect across the last few centuries as we tune into the archaic, lyrical sonnets that begat the talking blues–where technology has turned the rural music of Mississippi into the recitations of rappers in Bed-Stuy and Compton. Instead of an acoustic guitar, banjo, and washtub bass, a different kind of folk music is produced with two turntables and a microphone. The technology adapts along the way, but the end result is still the same: the man (or woman) on the street has a point of view and an experience to share, and if we are to revel in our common humanity together, it serves all of us well to prick up our ears and listen to the stories and folk tales of our friends and neighbors. We might even learn something in the process of tapping our toes and stomping our feet. Whether it is singing in unison or the tried and true dialog of call and response: these are the artistic forms that ask us to be mutually respectful and to honor one another. Folk music also serves as a clarion, so that we might all participate, pay attention, and understand the harmony of cooperation as its own reward. Peace.

Harry Smith: “I’m glad to say that my dreams came true. I saw America changed through music.”