Yesterday And Today

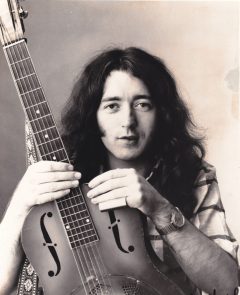

Remembering Rory Gallagher: The People’s Guitarist

The first draft of these words are written on Saint Patrick’s Day, about one of Ireland’s musical giants, Rory Gallagher. The blues guitarist was an electrifying live performer and musician’s musician, and while he never quite made it to the pinnacle of international superstardom before dying too young, he left a huge treasure of music and still has throngs of followers nearly 20 years after his premature death.

William Rory Gallagher (pronounced gal-a-her) came into the world March 2, 1948 in the small West Coast town of Ballyshannon in County Donnegal and grew up in Cork. It was a fitting blue collar start for a guy later known for his unadorned stage act, beat up old guitar, and flannel shirts. The home he grew up in had no record player, but young Rory and his brother Donal were encouraged by his parents (mom was a singer, dad played accordion), and the sounds he heard on radio, including Lonnie Donegan’s skiffle music, Elvis, and Buddy Holly. Soon, he discovered the blues of Muddy Waters and other American bluesmen on American Forces radio, staying up late for artists like Leadbelly and Big Bill Broonzy. He got his first guitar at age nine and taught himself to play, won a talent show at 12 with his acoustic guitar playing, and spent the prize money on an electric guitar. Quitting school at 15 to join the Fontana and Impact show bands, Gallagher was playing pop hit songs and touring Ireland and Britain while he made payments on his now-famous 1961 Fender Stratocaster. In short order, he learned to play harmonica, alto saxophone, mandolin, banjo, bass, and coral sitar. By 1965 he was touring U.S. air bases in Europe, playing more blues and rock in the show band sets, playing in the rock ‘n’ roll crucible of Hamburg, Germany, where the Beatles had honed their craft a few years earlier.

The show band circuit was a stepping stone for Gallagher as a sideman; in 1966 he was ready to front a band playing the kind of blues music he heard on the radio. Two versions of the blues trio Taste followed, first in Cork and then in London in mid-1968, with Charlie McCracken on bass and drummer John Wilson. Taste hit right in the midst of the British blues boom and were a big success, with two good studio albums in 1969 and 1970, one a British top 20 (On the Boards). They toured with Cream and were on the bill for their farewell concert and then in the US with Blind Faith. After two live albums, and a memorable, five-encore show before 500,000 at the Isle of Wight with Jimi Hendrix and The Who, the band fell apart at the end of 1970 following disputes between Gallagher and the band’s management.

Despite the early demise of Taste, the band gave concert and record-buying audiences their first “taste” of Rory Gallagher, and they drank it up. The first single was a sizzling blues rocker, “Blister on the Moon.” In addition to Gallagher’s originals, the early albums covered tunes like Hank Snow’s “I’m Movin’ On,” a country swing-blues that included tasty slide guitar and acoustic lead licks. “On the Boards” featured jazz guitar, exotic rhythm, and smoky sax solo by Gallagher-a sign of the eclectic turns he would take as a solo performer who could play bluegrass, jazz, country, and blues-rock, both plugged and unplugged.

Taste’s breakup set into motion Gallagher’s most prolific recording phase during the ’70s, as he formed a trio with bassist Gerry McAvoy and drummer Wilgar Campbell. He released two studio albums in 1971, a self-titled disc and Deuce, and he beat out Eric Clapton for International Top Musician of the Year. He had arrived. 1972 saw him in top Melody Maker’s Guitar player poll and his earliest solo live disc shows what the fuss was all about: Live in Europe, has a blazing versions of “Laundromat” and “Bullfrog Blues” that became fixtures in his live act for a decade, plus a killer acoustic harp/slide guitar take on the traditional “I Could Have Had Religion” that staked his claim to that tune from that record forward. He produced his own albums, and while the majority of his tracks with Taste and as a solo were originals, on many albums — especially live discs — he included cuts written by bluesmen like Muddy Waters, Leadbelly, Fulton Allen, and traditional songs given his special treatment.

On October 3, 1972 his and this writer’s paths crossed at a small club on El Cajon Boulevard called Funky Quarters. With likely less than 100 in the small nightclub, he played a gig that was otherworldly; for over an hour and a half he played acoustic, electric, country, jazz, slow, fast, all with equal ease. Gallagher poured his heart and soul into the performances as no other performer I have seen before or since, anywhere, and had that audience in his hands from the first tune. Small crowd, just another gig, but not for Rory Gallagher. His vocals were amazing and soulful yet tender with a growl and a yearning when needed. A virtuoso guitarist, he could do it all and would bounce from playing alone on dobro or mandolin, to finger-picked country-style blues, bluegrass banjo-style picking, or acoustic slide playing on delta blues-style songs. Then he would tear into full-band Chicago blues as well as hard blues rock, much with aggressive slide playing, in songs that often went on for nine or ten minutes. His electric guitar style included snarling tight finger vibrato, feedback-churning lead riffs, and knifing bottleneck passages that soared, slicing through the room, yet he could change the pace on a dime and play intricate jazz scales that sounded like Django Reinhardt.

1973 was another big year for his music with the release of Tattoo and Blueprint, and more of his signature tunes (including ones I had heard live, like “Cradle Rock” and “Walk on Hot Coals”). These also appeared on the landmark live double album Irish Tour ’74. This is not only known far and wide as a great live disc, but also for Gallagher’s resolution to tour Ireland at least once a year despite the political unrest there during the early ’70s, when other artists were often warned not to tour. His next studio effort was in 1975; Against the Grain featured a cover photo of his banged-up Stratocaster and some great new songs, including a picked acoustic version of Leadbelly’s “Out on the Western Plain.”

That cover photo is a whole story by itself. It was, according to Gallagher, the first Fender Stratocaster he ever saw — and reputedly the first in Ireland — and was in good shape when he got it in 1963. The guitar had most of its varnish peeled off, reportedly from the high alkaline content of Gallagher’s sweat onstage. It was stolen once, and the thieves left it out in the rain before the police recovered the axe, but the rain didn’t really affect the appearance much. The guitar has had many parts replaced, but Gallagher never considered refinishing it, feeling that the wear and tear gave it a sort of “tattoo quality.”

Gallagher continued to tour tirelessly, often more than 300 nights a year (by 1990 he had toured the US 25 times and appeared at the UK’s Reading Festival and Montreux Jazz festival more times than any other act). He not only recorded five studio albums in three years but also appeared on recordings by Muddy Waters, Albert King, and Jerry Lee Lewis. He was among the Rolling Stones’ earliest choices to replace Mick Taylor in 1974, thankfully passed over — a strong singer and songwriter like him would have languished as a sideman in a band like the Stones. The grind didn’t seem to affect his music, as 1976 saw the classic LP Calling Card. This one again flashed his versatility with the slashing slide work on “Country Mile” and an elegant, jazzy original “Edged In Blue,” one of his best songs. He took a break from the studio, but was back with a power-trio format in 1978 for Photo Finish. On this disc and 1979’s Top Priority Gallagher was flexing his guitar muscle more than ever; he still wasn’t selling millions of records, but had an established following and was playing big arenas.

Gallagher was a soft-spoken Irishman who had no appreciable personal life beyond his music and no long term relationship or children. He was a fan of detective books, especially Dashiell Hammett stories, and his songs often had titles and lyrics like “Public Enemy No. 1”, and “Cross Me Off Your List.” He was known for not using effects pedals or fancy equipment, often wore simple flannel shirts during his marathon shows, and shunned the limelight. He fought his record label’s plan to release “Edged in Blue” as a single, as he had no interest, as he put it, to be “some sort of personality”.

When Gallagher went back into the studio in 1982 for Jinx, the layoff didn’t show as he managed to make another major impact, cranking out memorable blues rockers like “Big Guns” and “The Devil Made Me Do It.” By this point, the heavy road schedule was taking its toll and he needed a rest. It would be five years before Defender. Though he no longer had a major record label, he still put the time in to sweat the details on his studio work, and the result was another solid album. When he recorded Fresh Evidence in 1988 (released in 1990), the physical toll of touring was evident on him, but he toured after its release. This disc, unlike any before it, took more time to record, and he used guest musicians. It also included an ominous tune, “Heaven’s Gate,” about a haunted, doomed man. The sense of foreboding was well founded, it would be his last record.

“The blues is bad for your health, it’s as simple as that; it goes with the territory,” Gallagher said after the rigors of the road started showing a physical toll on him, along with the alcohol and prescription medications. His return to touring was fateful: he had developed a fear of flying and was taking a powerful medication to overcome this. His alcohol intake combined with the drug for severe liver damage, but he stayed on the road. In January 1995; he collapsed onstage in Rotterdam and the tour was cancelled. It was the beginning of the end. Hospitalized in March for liver failure, he underwent a successful liver transplant but developed a MRSA infection afterward, and died on June 14 at age 47. Members of the music world sent their condolences, and thousands lined the streets of Cork to see him laid to rest.

Other recognition took longer, as his legacy has gradually grown with time since his passing. In 1997 a tribute sculpture to Gallagher was unveiled on a street renamed for him in his hometown of Cork, where there is also a Rory Gallagher Music Library. There are plaques in both Dublin and Belfast dedicated to him and the Dublin one is near a life-size bronze statue in the shape of his Stratocaster guitar. A street outside Paris has been renamed Rue Rory Gallagher. In 2010, a life-sized bronze statue of him was unveiled in the town center of Ballyshannon, where an annual Rory Gallagher blues festival is held in his honor. He is listed on just about everybody’s “Greatest Guitarist of All Time” lists, and belongs in the top five of the blues-rockers. He also belongs in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, and there are multiple online petitions to get him in. Just about everyone agrees that along with Van Morrison, Gallagher was the first Irish blues or rock musician to gain international prominence, setting the stage for several that followed, including Thin Lizzy and later acts like the Pogues and U2. Many of his legion of fans refer to Rory Gallagher as “the people’s guitarist,” a title that would probably suit him just fine.