Tales From The Road

“May the mother of God have mercy on you…” A Conversation with Tony Sheridan

Tony Sheridan

The Beatles backing Tony Sheridan at the Top Ten Club, 1962.

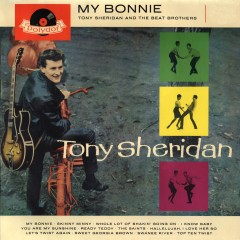

It was the first day of summer on June 22, 1961 when John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison, and Pete Best found themselves at Fredrich-Ebert-Halle in Harburg, Germany, to cut their very first professional recording. Liverpool’s most famous quartet was in the middle of their second (of five) German expeditions where they were woodshedding six hours a night, eight days a week at an establishment called the Top Ten Club in the Reeperbahn district of Hamburg (infamous for its after hour offerings of strip clubs, prostitutes, drugs, and organized crime). At a time when the social mores of the era were having the lid blown off of conventional attitudes, it was here among the denizens of the Reeperbahn that the Beatles truly came of age, due in part to their budding friendship and musical collaboration with fellow Brit Tony Sheridan. Producer Bert Kaempfert heard Sheridan and the Beatles playing their mashed-up version of American rock ‘n’ roll at the Top Ten and thought that they made a vital sound together, so he made a series of recordings with them, mostly featuring Sheridan’s voice and guitar. A 45 rpm single was issued from these sessions on October 23, 1961, coupling an old Scottish folk ballad with a Christian hymn and dressing it up in Levis and black leather jackets (“My Bonnie [Lies Over the Ocean]” backed with “When the Saints Come Marching In”). No one knew it at the time but it was a record that would change the course of 20th century popular music by inadvertently bringing the Beatles to the attention of NEMS manager Brian Epstein and sparking into action a series of events that led to a worldwide cultural revolution. And Sheridan was an essential ingredient in that catalytic flint, which led to a musical explosion.

It’s been 50 years since those fabled sessions in Hamburg, and Sheridan is still rocking and rolling in 2012. His life is certainly a compelling saga from the time of his birth in Norwich, England (May 21, 1940) at the onset of World War II, being abandoned as an infant and subsequently reunited with his mother, becoming deeply affected by the mid-fifties Skiffle craze in Britain (like many of his other teenage contemporaries), and growing up to find himself at the age of 18 on British television playing rock ‘n’ roll on a weekly basis. In 1967 he was made into an honorary captain of the U.S. Army after touring Vietnam and entertaining the troops. In the 1970s he performed and recorded with Elvis Presley’s TCB Band. Moreover, the accumulated wisdom that came from his worldly travels was reflected in his songwriting, particularly on the excellent 2002 compact disc Vagabond. Sheridan eventually settled down near Hamburg in Seestermühe where he continues to enjoy life.

Suffice it to say that the old rocker still has fire in his belly and to prove it he will be in town to do some recording and to perform with the West Coast Beat Brothers on October 27 at the San Diego Beatlefair at Queen Bee’s Arts & Cultural Center, 3925 Ohio Street. The event is being produced by Dave Humphries and Robbie Taylor in coordination with Alma Rodriguez and tickets can be purchased at www.queenbeessd.com. Also performing on the bill are the Dave Humphries Band, the Baja Bugs, Bart Mendoza and True Stories, and Help!

The last time Sheridan was in San Diego I had the chance to sit down and mach schau with him on behalf of State Controlled Radio. His stories had me laughing for hours…

Can you tell me how being from Norwich shaped your world view?

Well, I could talk about that for hours… but being born at the beginning of the Second World War in Britain was not an easy thing. Babies should not be subjected to all that fear and God-knows-what when the bombs are going down. A baby should grow up in a slightly more peaceful atmosphere, one would think… and it was one of the reasons that we later became interested in the infectious essence of rock ‘n’ roll as we heard it — raw and pure — in 1956.

When we heard that in Britain it changed our lives. There was nothing approaching that before in England and it shook me up. When I was 15 and 16 I thought, ‘Hey! This is the most wonderful thing I’ve ever heard in my life,’ and ‘My God, could I possibly do that myself?’ All that went through my mind and very soon I told myself, ‘Of course you can do that, too. Maybe even better.’ So a decision came about to do rock and roll very early.

Was Elvis the most important influence for you at that time?

He was the trigger figure. But coming from a classical household where my mother played piano and was a contralto in her spare time, she was also a fervent Christian. I didn’t hear anything but classical or sacred music up until my puberty.

Do you have memories from the end of World War II?

The American influence was very strong on us kids, lots of soldiers around in uniforms, but we had seen a couple of films. And the real music came from America. Even Johnny Ray and stuff like that influenced us a great deal. Before rock ‘n’ roll Johnny Ray was almost a trigger figure but it took an Elvis to do it. The American music that the GIs brought with them, which ranged from blues to jazz: Sinatra, Ella Fitzgerald, Billie Holiday… consciously when you are a kid if you hear that sort of thing, if you hear Glenn Miller, you hear something American. This is so obvious to a kid: that is not British. We associated the music with the better looking uniforms, the nicer badges, their way of walking was somehow a little freer or something… we kids saw that. And we got chewing gum.

Speaking of chewing gum, by the time you heard Lonnie Donegan were you familiar with people like Leadbelly and Woody Guthrie?

Not at that time, because Donegan introduced us more or less to Leadbelly, etc.

What happened when you heard Lonnie Donegan?

Donegan, who got his name from Lonnie Johnson, played that music very well indeed. Donegan was a bit of a genius. He was that guy who had to happen at that time in order to turn this into something that was important. Looking back it is easy to see the connection between being born and Hitler and the Beatles… without Hitler there wouldn’t have been any Beatles. Simple as that.

Because if this guy [Hitler] helped cause the Second World War then kids like John Lennon and others wouldn’t have been so intimately part of this horrible, loud bombing thing, which just scares the shit out of you at a very early age. Life is just confusion. To grow up with the mentality of deprivation — I haven’t been loved, nobody loves me, I’m a horrible guy — that was very prevalent during the war years. Kids were rejected; their mothers had to give them away, put into a child’s home. That happened to me… this was the psychological reason for why a lot of things went down later. Like the music. Or your personal relationships with women, they are all intimately connected to your early childhood.

The fact that a few guys came out of the rubble like Lennon and McCartney and a few others, too, the fact that we were given the gift to transform this negativity: war, pain, deprivation… into some kind of musically acceptable energy for the whole world, it was something therapeutic I felt at the time that it came out. Then we were just dealing with our puberty urges and putting most of that energy into the music ’cause the girls weren’t really available at that time in history…

How did you get involved with Jack Good and the “Oh Boy!” program on ITV?

Jack Good? You doubtlessly heard about The 2i’s Coffee Bar on Old Compton Street [in Soho, famous for many musical discoveries]… that’s where we met. One day Jack Good came in and we knew about his show; he had a bit of a reputation of being sort of an avant-garde television director/producer who came from Oxford, an intellectual who was deeply and fervently into rock ‘n’ roll. Jerry Lee, Elvis, Chuck Berry, Fats Domino, Little Richard…

The Everly Brothers?

And then you have the others [laughs]. Eddie Cochran, Gene Vincent…I knew those guys very well…

So well that Sheridan ended up performing on a package tour with both Cochran and Vincent in the spring of 1960 and narrowly missed being in the automobile accident on April 17, 1960, which left Cochran dead and Vincent badly maimed for the remainder of his life. In 2010 Sheridan told RTÈ (Irish Radio)

And then I heard they’d had this accident and that Eddie had been killed. The next day it really hit me; I could’ve been in that car.

After Cochran and Vincent’s car crash Sheridan’s next move was to go to Hamburg, Germany.

The subject came up of going over to the red light district and playing every night in a club — not just half an hour or an hour or something, but all night. And that sounded so attractive: ‘What! Playing all night! Wonderful.’ Like ’til two in the morning or more. Because previously the longest gig I’d ever had I think was 45 minutes. I was playing with my group, I was on TV… the idea of playing all night to a young audience and being able to play anything I wanted, as loud and as vulgar as I wanted, just to let it all out. That was not allowed in Britain, there was nowhere that you could do that. So, something inside of me went ‘click’ and this was the right thing to do and you’re now going over to the ‘enemy.’ Of course, you’re getting back at your mother this way too, for the pain she caused you as a little child. You’re getting right back at a few other relatives as well who don’t want to see you going over to Germany to play.

I wasn’t part of the Beatles by any means, I was just sort of the ‘house singer’ if you like, I was a guy they were looking up to, all of them at the time. And I was asked, ‘Tony, would you mind playing with this group who would love to back you for the next three or four months? Can you imagine playing with this group and making a go of it?’ And I was like, ‘Yeah! I think so…’ And the fact that nobody recorded a single evening, that’s such a shame when I think about it. In those days it just sort of went past. Everything we did was NOW. It was just a practicing ground, there was nowhere in the world where you could practice [in public] that long and intensively every night. You could play wrong chords [at the expense of the public], sing too loud, sing the wrong melody, forget the words, whatever — it didn’t matter. There was nowhere else in the world where you could do that and get away with it. And then, at the other end, you either come out being good — really good — or you realize you haven’t got what it takes.

But the thing in Hamburg is that many singers and musicians gave up more or less because they felt like they couldn’t come up to a certain quality. They weren’t having any fun anymore either. When you discover that you’re shit I don’t think that’s very good for the ego. But it certainly saved us from a lot of bad records!

Being a musician has always been a help I’ve found when getting along with people. You know I went to Vietnam so I did that to myself for another reason… it was a deal.

Part of your karma?

Um, if you want to call it karma, I don’t particularly adhere to that word. The thing about karma is you don’t need a word for it. It’s a natural balancing out situation. As long as things are fairly well-balanced then everything’s all right.

And when they’re not, the Universe has a way of making sure they go back into balance…

Absolutely. For individuals, groups, nations, and the world itself.