Tales From The Road

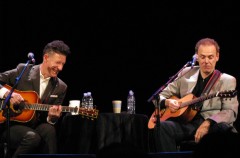

Lyle Lovett and John Hiatt and their Circle of Song

It seems in most cultures and tribes throughout history the communal circle is something regarded as holy. It eventually leads to rhythm, dance, and stories. Then comes the inevitable act of putting the story to music. The song is a major ingredient of any sacred circle. It’s been true for centuries. To create holiness — that thing that sets all moments of life apart from our daily struggles and triumphs — music must be there at the center, be it the simplicity of a chant or the movement of dance, or the telling of story in melody, or the complexity of a symphony, music is always there, our constant companion. Inevitably, it grows and captures our imagination through the vehicle of songs and stories.

If there have ever been two great and classic carriers of the sacred song, it would be John Hiatt and Lyle Lovett.

The “song circle” or “guitar pull” is a long tradition that goes back to the days of the original singer-songwriters of Nashville and Austin in the ’60s, when artists like Willie Nelson, Kris Kristofferson, Mickey Newbury, and Roger Miller could be found trading off songs in some smoky club or greasy kitchen in the backstreets and alleys of the great music towns. According to Roger Miller, the term came from the fact that in their struggling days, most songwriters would be found with only one guitar among them. Later, such occasions became standard practice and were breeding ground for future legends. Artists like Guy Clark, Townes Van Zandt, Steve Earle, and Rodney Crowell would make their way and take their turn at the center of the flame of such circles of songs, pulling the guitar between and pounding out future classic songs.

When Texas troubadour Lyle Lovett and Indiana-born John Hiatt launched out together for an acoustic series of tours, sharing the stage and trading songs, they were embarking on an extension of the old guitar-pull tradition that helped to begin the era of the singer-songwriter in late ’50s and early ’60s. It was an idea also drawn from past gigs at Nashville’s Bluebird Café and Austin’s Cactus Café. Both artists also toured with a series of national shows that included both artists Guy Clark, Townes Van Zandt, John Stewart, and Steve Earle.

So when they took the stage together a few years ago, something magical happened. They created that same circle of song, once formed in private spaces of time’s past, now held in public at intimate venues. To the surprise of artist and audience alike, that same holiness prevailed, which was once held with a hushed regard over the last five decades. It was as though the spirit of Mickey Newbury, Townes Van Zandt, and even Hank Williams stood guard.

When Hiatt and Lovett join together on stage, the space they create is something to behold. According to journalist Nancy Nutile-McMenemy at the Internet site JamBase, during their recent show in Boston, “The two are so comfortable with themselves that they make you feel like you are sitting in the living room with them, getting to know them better through their songs.”

And while the homespun feel is the format of the circle on the stage that Hiatt and Lovett create, it’s the stepping inside the sonic sphere of song as they preform that is most revealing. With each artist there is the immediate relief of wry humor, a touch of sarcasm, irony, and depth of soul as real as the Mississippi Delta or the Rio Grande, which runs through their work. The range of performance and songwriting skill that forms their bond for all to experience in concert is palatable. After all, they have nearly a century of songwriting experience between them.

John Hiatt’s success in music came from a road of dues paid on the not-so lucrative songwriting streets of Nashville in the mid-’70s. He was the newly arrived adolescent Midwestern street urchin, ready to ride his way to overnight fame. However, his success would be more of a slow-build than a sudden phenomenon.

His childhood in Indiana was not always easy as well. When he was nine his 21-year-old brother committed suicide. Two years later his father died of a terminal illness. His childhood comfort was found in IndyCar Racing and the music of Elvis Presley and Bob Dylan. They were the starting point that would soon find young Hiatt absorbing the work of Hank Williams and Muddy Waters. During his teen years, after learning guitar and beginning to write songs, he joined local bands.

By 1971, at 18 years old, Hiatt moved to Nashville where he was hired as a staff songwriter for a publishing company for $25 a week. Not being a trained musician, he couldn’t write music or charts, so he recorded 250 songs that he wrote for the company as rough demos. Over the next few years Hiatt joined the band White Duck, which released two albums and scored a hit with the Hiatt-written, “Train to Birmingham.” He also performed around town as a solo act and grew in stature as an artist to keep an eye on.

As his solo fortunes eclipsed that of White Duck, Hiatt’s song “Sure as I’m Sitting Here” went to top 20 in 1974 to become a latter day hit for the successful ’60s band Three Dog Night.

It was as a solo artist from 1974 to 1979, recording a string of commercially unsuccessful albums that were nonetheless adventurous and engaging, when Hiatt developed a sound from his country roots-rock beginnings to become an influence in the new wave-influenced rock of the late ’70s. It would find him in the company of Elvis Costello, Nick Lowe, and Dave Edmunds.

In 1982, after recording another string of critically successful albums that were commercial failures with MCA, Hiatt collaborated with Jim Dickson and Ry Cooder to write “Across the Borderline,” which has become a modern classic. It was the theme song for the Jack Nicholson classic film The Border, sung by Freddy Fender. Ahead of its time, the song speaks empathetically from the experience of the undocumented Mexican immigrant who crosses the border in hope of redemption only to be bitterly disappointed. Today, after being recorded and/or performed by Bob Dylan, Willie Nelson, and Bruce Springsteen, the song stands beside Woody Guthrie’s “Train Wreck at Los Gatos Canyon (Deportee)” as a classic folk song about the inside experience of undocumented immigrants.

In 1987 Hiatt released his now classic hit album Bring the Family. The album was recorded with Ry Cooder, Nick Lowe, and Jim Keltner. That same group of musicians would form Little Village, recording one eponymous album around the same time period.

Bring the Family stands today as one of the best albums by a singer-songwriter recorded in the ’80s. With songs like “Memphis in the Meantime,” “Have a Little Faith in Me,” and “Alone in the Dark,” the album has since found its way into movies and television shows when a strong song is needed to bring home a dramatic moment, as happened memorably in the hit movie True Lies with Jamie Lee Curtis and Arnold Schwarzenegger. Bonnie Raitt famously scored a top ten hit with Hiatt’s “Thing Called Love,” from her Grammy-winning Nick of Time.

Since Bring the Family, Hiatt has gone on to create a legacy of solid albums and secure a place in the ever-growing Americana Music-roots movement. Today, he is one of the genre’s elder statesmen.

As rough and sometimes strewn with tragedy as John Hiatt’s rise to fame as a songwriter was, Lyle Lovett’s was somewhat story-driven with traces of comedy. Raised in Houston, Texas and graduating from A&M University in College Station, Texas, where he made friends with future successful songwriter Robert Earl Keen, and together wrote “The Front Porch Song,” Lovett was a songwriter from the get-go. By 1980, at 23, he was a known commodity around Texas songwriting circles with his own wry sense of humor and original take on song craft. Lovett had a different vision of American music than his peers. He was part smoky jazzman, part hard-core Texas country singer. He couldn’t settle on one or the other, so he brought both styles with him throughout his prolific, Grammy-winning 29-year recording career. With his first two albums — his self-titled debut and 1987’s Pontiac — finding him straddling the line between comedy and tragedy with a sometimes light-hearted world view similar to that of Randy Newman and Townes Van Zandt-influenced country blues, he created his own unique, reflective vision that called up the hopes, dreams, and urban realties that drove him on songs like “If I Had a Boat” and “God Will.”

The first album, which has defined much of his work since its release in 1988, is Lyle Lovett and his Large Band. On it, he moves through six blues-jazz songs that include big band brass arrangements without a trace of country. The second half, the final six songs, are uncompromising country-western with original titles like “I Married Her Just Because She Looks Like You,” and a faithful pedal steel-driven recreation of the Tammy Wynette classic “Stand By Your Man.” This album has become a career template, especially for concerts and live albums, like 2007’s Grammy winning It’s Not Big It’s Large, demonstrating how in concert he brings out the finest in live big band-jazz alongside performances of country songs with Texas songwriting icon Guy Clark.

He also attracted the attention of iconic filmmaker Robert Altman, leading to being cast in the 1992 classic film The Player. It was on the set that he met actress Julia Roberts, which led to a two-year marriage and brief innocuous appearances in the tabloids.

Thus began his work in film, which would include another soundtrack for Altman, Dr. T and the Women, and teaming up with Randy Newman on “You’ve Got a Friend in Me,” for the film Pixar film Toy Story.

As John Hiatt and Lyle Lovett bring their show to San Diego, it’s a rare opportunity to see two of today’s finest songwriters in their artistic prime light up the stage with song and story. As they form their own circle of song together, it is also a chance to witness a nearly 50-year-old tradition by two artists, who are equals as they illuminate each other and the audience with the best in American music, songs, and stories.

Lyle Lovett and John Hiatt will appear at the California Center for the Arts on Sunday, November 8, 340 N. Escondido Blvd., 7:30pm.