Tales From The Road

John Prine: An Appreciation

John Prine was a gentleman songwriter whose love for life shot through his music like light beams. He was the middleman between hope and despair, an ambassador of song who brought comfort and companionship to his legions of fans through the warmth of his voice, a perfect vehicle for the portraits of desperate characters he worked into the hearts and minds of many disenfranchised souls. For 50 years, he entertained, enlightened, humored, and inspired us with tales of old folks, lonely misfits, childhood paradise, and burned-out rodeo queens. He was able to achieve in a five-minute country song what most authors of fiction set out to in a 300-word novel. Like Woody Guthrie, Prine was a timeless journeyman who reported on the human experience with deceptive simplicity. He made us laugh, cry, think and feel deeply, and gave breath to singular singers like Bette Midler (“Hello in There”), Bonnie Raitt (“Angel From Montgomery”), Johnny Cash (“Paradise”), and George Straight (“I Just Want to Dance With You”), through the power of his words and the unique eccentricities in his mind. He was the embodiment of three chords and the truth.

But Prine’s songwriting alchemy was especially conjured when he delivered a set of solo acoustic songs. “When I would be opening for John,” recalls Prine’s longtime friend and brother in song, Chip Taylor (“Wild Thing”), “one of my favorite things to do after I finished with my show was to go in the wings and watch him. I’d just listen to those songs. He would do them a little different every night. It was like going to the best kind of church. It did what church is supposed to do, raise your spirit, make you a better person and have reverence for the human spirit. Just sitting there listening to John Prine, I’d be having one of the most beautiful experiences of my life.”

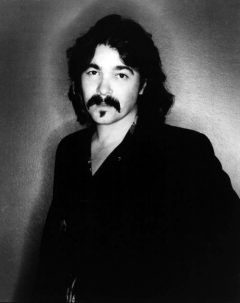

Born and raised in the Maywood, Illinois, Prine came onto the Chicago folk scene as the seventies singer-songwriter movement gained momentum. Artists like Prine, Jackson Browne, and Bruce Springsteen cropped up around the country, all hailed as “the New Dylan,” as Dylan himself hid out, trying to escape the dubious “voice of a generation” tag given to him by the public. If anyone ought rightfully lay claim as Dylan’s successor, Prine’s songwriting prowess earned him the honor. But he was so much more. He was a Dylan’s peer, a fact immediately evident to Texas songwriting legend Kris Kristofferson, whom Prine partially credits credits for his early success. Late one evening in 1971, through the friendly persuasion of Steve Goodman, Kristofferson walked into a small Chicago pub to see Prine, who the year before caught the ear of local critic Roger Ebert, who penned a review for the Chicago Sun Times titled “Singing Mailman Who Delivers a Powerful Message in a Few Words.” Prine was so special, he inspired an oft brutal film critic to write a glowing review of his show. It seems anyone who stumbled onto Prine was immediately drawn in by the eminent magic of this incomparable songwriter. “By the end of the first line,” Kristofferson later recalled, “we knew we were hearing something else. It must’ve been like stumbling onto Dylan when he first busted onto the Village scene.”

Kristofferson promptly invited Prine to open for him at the Bitter End in New York City. That evening, Dylan producer Jerry Wexler was in attendance. The following day, he signed Prine to Atlantic Records. Prine’s country-tinged self-titled debut vocally hearkens The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, and features some of his most beloved songs, including “Angel From Montgomery,” “Hello in There,” “Paradise,” and “Far From Me,” a song Prine has said Dylan knew and played for him at Carly Simon’s home in the early seventies. The album also includes Prine’s iconic “Sam Stone,” a commentary on the post-traumatic stress and drug addiction prevalent in soldiers who returned from Vietnam. The album made a lasting impact on Dylan, as he revealed Prine as one of his favorite songwriters in a 2009 Huffington Post interview. “Prine’s stuff is pure Proustian existentialism,” Dylan noted. “Midwestern mind trips to the nth degree. And he writes beautiful songs. I remember when Kris Kristofferson first brought him on the scene. All that stuff about “Sam Stone,” the soldier junky daddy, and “Donald and Lydia,” where people make love from ten miles away. Nobody but Prine could write like that.”

On more than one occasion, Dylan pointed to the song “Lake Marie” from Prine’s 1995 effort, Lost Dogs + Mixed Blessings, as his favorite. While Prine’s catalog is filled with classics, “Lake Marie” may just be his greatest. The song feels like an impressionistic painting depicting fragmented memories as Prine throws out a parlor trick, using film noir imagery to tell this story of the lakes and a murder. Then comes and the gut punch—the narrator’s grief over the death of his relationship brings the song to its climatic finish. Twenty years ago Prine began using the song to close his show complete with Rocky Horror Picture Show-style participation from his devout audience.

But if his songs often featured tragic characters and stories, he didn’t stay on the same sad note for long. He was often funny. Absurdly so. During the weed-strewn days of the of the seventies, another track off his eponymous debut, the opener, “Illegal Smile,” was adopted as the pot smokers anthem, even though Prine denied its link to the drug. But the song was an immediate introduction to his dark humor that extended to songs like “Dear Abby,” from his 1973 classic, Sweet Revenge. Prine wrote the tune while in Rome, unable to find English newspapers except for one that included the famous advice column. The result is a hilarious piece of small-town news that only Prine could write. Sweet Revenge also features Prine’s irreverent take on death on “Please Don’t Bury Me,” one that soars to cartoonish heights and could be a worthy Saturday Night Live skit. Prine opens the song with the disarming line, “Woke up this morning, put on my slippers, walked in the kitchen and died.” It’s like having the floor fall from under you in an amusement park spin ride. And then there’s the Cold War-inspired tune, “Space Monkey,” a satirical nostalgic odyssey he wrote in his kitchen with Peter Case. It’s perfect example of his absurdist humor.

“Me and Peter were gonna write this three-chord love song,” Prine says on his 1997 album Live on Tour. “And instead, we wrote this song about a monkey that the Russians put into space in the fifties. And they forgot about him and he didn’t come down until the nineties when there wasn’t any Soviet Union left. So, after twirling around for all those years at the very least he was expecting maybe a parade when he got home. Needless to say, he was disappointed.”

On “Jesus, the Missing Years,” from his 1991 Grammy-winning album The Missing Years, Prine takes his humor to religion, looking into a messianic mirror and seeing himself, in this cloaked, epic autobiographical tale, the savior of the song discovers the Beatles, plays with the Stones, and even opens up a show for old George Jones. Now, all of this turns out to be one great big cartoon with a tragic foreshadowing. Like many of his songs, if there is a smile or chuckle, there may be a tear beneath the laughter. It is this multi-level of meaning that runs through most of Prine’s tongue-in-cheek songs that establish his iconic brand.

When Prine passed away on April 7, 2020, from COVID-19 complications, it came as a shock to the music community. He was 73 years old, but still hitting his stride. A two-time cancer survivor, Prine was working on an autobiography and writing songs for the follow-up to his 2018 highly celebrated effort, Tree of Forgiveness, his best-selling album to date. It reached number five on the billboard charts and earned him the 2019 Americana Music Award for Best Album. And, earlier this year, Prine was finally bestowed with a Lifetime Achievement Award in Songwriting at the 2020 Grammys. He didn’t seem destined to leave this earthly world anytime soon, but rather ready to go the distance. He did not appear to have one foot in heaven. But, as the song he wrote many decades ago said, “He was in heaven before he died.” He was.

Ironically, Prine’s final days found him on a European tour playing Paris for the first time in his career. According to Rolling Stone magazine, his last time on stage was on February 13, 2020, at the 500-seat capacity Café de La Danse in the heart of Paris. Prior to going on stage, pain caused him to sit down during the show. Later he would find it was because of a collapsed hip. Still the sold-out show went on and Prine delivered a magical set that left the Parisians wanting more.

Following his return to Nashville and a successful surgery, the recovery prognosis and a return to performing looked good. However, it was not to be. John Prine had completed his earthly journey. It was as if he said in the words of “Lake Marie,” his closing song, “we gotta go now.”

After 50 years, the stages where Prine brought his rich, full portraits of life in song with all their humor, pain, and glory will now be empty. We won’t see him coming through our towns anymore, nor will we see the likes of him again.

The end came faster than we wanted or expected, but John Prine created a legacy that will carry on through this tragedy and the crisis of the day. His life was complete with his art, his family and friends. He was a force who changed the American landscape for the better. He was respected by his peers and young songwriters like Jason Isbell, the Avett Brothers, Kacey Musgraves, Hayes Carll, Brandi Carlisle, Sturgill Simpson, and Tyler Childers, all of whom celebrated him abundantly for years before his passing. He went out on top and full of love.

Of course, in true Prine fashion, he gifted us with a perfectly quirky gospel finish to his life that wouldn’t allow for too much sadness in the wake of all this tragedy. “Tree of Forgiveness,” he fittingly closes out his final album with a satirical, heart-on-his-lapel vision of the day he arrives in Heaven, where he opens a nightclub called Tree of Forgiveness and forgives everyone who ever did him harm, leaving fans with the comforting idea that he truly is living out his absurdist vision of a celestial utopia. If so, at this moment, Prine may be drinking a vodka and ginger ale and smoking a cigarette that’s nine-miles-long. I know he must be writing a song with Paradise waiting a half mile away from wherever he is.