Yesterday And Today

Balboa Stadium: Music in the Landing Pattern

The Beatles at a press conference before their appearance at Balboa Stadium, 1965

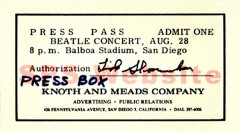

Press pass to the Beatles concert

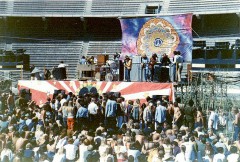

Concert goers at Balboa Stadium. Courtesy of Gary Ra'chac.

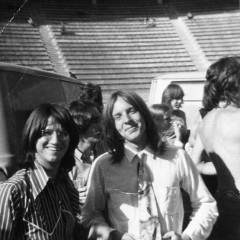

Richie Furay of Poco (left) with Gary Ra'chac in 1969. Note Gram Parsons in the background. Photo: Mick Garris/Courtesy of Gary Ra'chac

The Eagles at Balboa Stadium, 1977

Stephen Stills adjusted his Martin flat-top closer to the mike, while Graham Nash and David Crosby glanced at each other, launching into the bridge of “Suite: Judy Blue Eyes.” The crowd spread out on the grass below the stage was a sea of hippie humanity in the crisp 1969 air, mellow and quiet, settled on blankets in a lightly pungent smog of incense, marijuana, and tobacco smoke. Then, abruptly in mid-song, a loud roar rumbled overhead. The band stopped singing as one, and froze in place; all eyes turned skyward.

Almost directly overhead, the PSA jetliner zoomed in, gear down, the scream of its engines resounding like metallic thunder through the cavernous concrete of Balboa Stadium. Then, as quickly as it had approached, it was gone with a fading echo. After a few seconds, the trio of statues onstage came to life and the harmonies of the song resumed, exactly where they had stopped, without missing a beat.

While many longtime San Diego music fans remember Balboa Stadium primarily for the famous visit by the Beatles in August 1965, the locale also served as the region’s stadium rock headquarters for over a decade; in the age of the outdoor music festival in the late sixties it was the place many local music fans, including this author, saw the same bands that wowed the world at Woodstock.

A big, concrete horseshoe built in 1914 in connection with the Panama-California Exposition that generated many of Balboa Park’s buildings, the venue’s main claim to fame through the fifties was as the largest high school football stadium in the country, for adjacent San Diego High. The San Diego Chargers changed that, adding a second deck in 1960 to increase the seating capacity to around 34,000. These were not luxury boxes; the place had concrete benches for seats. The facility was used for the Chargers’ AFL games and a few other functions (I saw a track meet there in June 1965, Jim Ryun was 18 years old and almost broke the world record in the mile). Though built earlier, Balboa seemed in some ways a miniature, poor-man’s LA Coliseum, with a similar pillared balustrade on the open end and press box above the bleachers.

The Beatles drew 17,000 (far from a sellout) for a 12-song set at Balboa in August 1965, but most of the emerging rock scene’s acts stayed within four walls, and the Chargers occupied Balboa most summer and fall weekends until San Diego Jack Murphy Stadium in Mission Valley went up in 1967. The Doors topped a bill on July 8 that year, right when their “Light My Fire” was first hitting the charts, but I was still catching the Who and Cream months later, sitting in the deafening confines and hard concrete floor of the Community Concourse exhibit hall. Most other top acts seemed to play the Civic Theatre, or Sports Arena if they could draw enough people. Often, bands would play both as they built a fan base. Then, in September 1968, Jimi Hendrix came to town.

Though many chroniclers now point to Hendrix’ 1969 Sports Arena appearance as an all-time benchmark for local live music, the Balboa set was equally noteworthy (and I was lucky enough to attend both). Vanilla Fudge and Soft Machine opened the evening, and the Machine played without a guitarist (the guy they fired shortly before turned out to be Andy Summers, later of the Police). The early jazz-rock band’s bassist played great solos of his own using a fuzz pedal. Hendrix arrived by limousine, said to be due to a late plane arrival, and told the crowd he was dead tired; the stage antics he was becoming known for were mostly absent. He mostly stood and played guitar-fantastic, shreiking, and fast lead guitar unheard of or even imagined before that night by anybody in the crowd, including the 19-year-old aspiring blues-rock guitarist yours truly several rows up in the second deck. Though his trio had a great drummer, Hendrix sounded like a whole band by himself, one with three guitars, a band with a lead guitarist from another planet.

“Festival seating” limited what patrons could carry into Balboa in the way of bottled alcohol, but times and security were more laid back then. Flasks of wine seemed to be okay at most events, and quilts or cushions for sitting were the norm. A few of the more colorful characters from the local concert scene could always be counted on to be seen circulating around. I still have the blue wood love beads and buckskin fringe jacket from those days (though I’m too corpulent for the jacket). Like Woodstock, Altamont happened in 1969, but the vibe at all of the Balboa Stadium concerts seemed to be strongly positive, people out to have a good time together and hear good music in the sun. The concerts were almost exclusively summer and fall affairs, and the local weather played a big part.

After Hendrix, the Balboa/Woodstock connection, of sorts, continued through 1969. Three weeks before the New York festival, Jefferson Airplane and Ten Years After played Balboa with the Sons of Champlin. Seating on the grass for the afternoon show was $3.50 (high for the time; Hendrix tix started at $2.50), and there were trade booths and vendors; an original poster for the show can be had online for $250. The Airplane’s music was sloppy and meandering, while Ten Years After smoked the crowd with raw blues energy, despite Alvin Lee playing identical solos in every song. In October Country Joe and the Fish were on the bill, with Poco and headliner Chicago. The Fish were crowd favorites, a show full of the kind of Bay Area acid-rock and blues that had become familiar during the two previous years. Though not a Woodstock act, Chicago Transit Authority, as I knew them until that day, tore the stadium up and had everyone in the audience standing throughout their whole performance. The music was political with a huge and edgy horn sound; they seemed to have five lead singers, and the star was dazzling guitarist Terry Kath. Showing no evidence of the adult contemporary softies they later became, Chicago would play Balboa two more times before the stadium was demoed.

Neil Young had a big following of his own when he joined Woodstock vets Crosby, Stills, and Nash. Buffalo Springfield had played locally several times in their turbulent two years together, and these guys were already country-rock royalty to the big crowd on December 21, 1969 for one of the rare winter Balboa concerts. Canned Heat completed the flower generation-nation tableau on the perfect afternoon, with new guitarist Harvey Mandel joining Al “Blind Owl” Wilson and other members of the famed boogie band for what had to be one of their all-time best shows. CSN&Y followed, jet landings aside, a band at the their peak playing for over two hours. Unplugged, jamming, playing as individuals, in combinations, it was unforgettable music. Many in the crowd were seeing trails already from various chemicals, but it was easy to sense that the sounds that afternoon were special; a “contact high” from the music lifted everyone.

The seventies brought many other concerts (over 20 total), though it was 1974 before more of the Woodstock lineup would appear — when Santana and Sly and the Family Stone played. In September 1973, Steely Dan appeared during their only tour, opening for Elton John. In April 1975, Fleetwood Mac played its first concert featuring Lindsay Buckingham and Stevie Nicks (and while I swear I remember being there for that show, my wife says I wasn’t, and I trust her). Just a few of the other blue chip acts to play Balboa by the end of summer 1976 were War, Rod Stewart with the Faces, the Eagles, Jethro Tull, the Allman Brothers Band, Aerosmith, and Jeff Beck.

Interstate 5 through downtown, what used to be called the “crosstown,” was finished in the late sixties, forming a loop that surrounded the stadium on two sides, walling Balboa off from the nearby park. In a way, the downtown “S” curve was built because Balboa Stadium was in the freeway’s path. In the late ’70s, the upper deck and columned entrance went down to the wrecking ball, part of an earthquake retrofit. The remainder soon followed, and the Balboa Stadium that exists today is two sets of concrete bleachers on either side of a track (where I watched my youngest son sprint in a high school meet) and football field — for San Diego High. In 2012, except for a few bands, stadium rock is just about gone. But not forgotten, and Balboa Stadium gave me and other local folks some pretty great music and memories.