Yesterday And Today

A Story About Frequency Modulation

When Stephen Hawking died, I figured I better try to sound smart. So I read Hawking’s Brief History of Time “cover to cover,” first the front cover, then the back cover. Plus, I stared at a few pictures inside as I tried to become one with such concepts as “particle-wave duality.” Yet, in the myriad of confusing terms–quark, point particle, Planck length–one term jumped out at me: “frequency modulation.” I remembered “frequency modulation” from high school. It’s the term that gives us the “F” and the “M” of FM radio.

FM radio was first tested in the 1930s. The sound quality was superior to AM. But the FM radio signal was not as far-reaching. So FM couldn’t compete with AM during the Golden Age of Radio. Then, television took over radio’s spot in popular culture. AM was delegated to live sports, religious programming, and teeny-bopper Top 40. In all of these cases, sound quality wasn’t particularly important. Eventually, FM radio found its niche among music aficionados who tuned in to classical, symphonic music, and jazz. Ironically rock n’ roll started on the AM, but later moved over to the FM as it grew into its own as a semi-sophisticated musical genre.

FM radio’s novelty caught on with a broader listenership with the music revolution of the 1960s. Replacing the classical music devotees, a younger group of rock music listeners demanded that radio provide the same “fidelity” as the home hi-fi stereo system. Albums such as Pet Sounds and Sgt. Pepper were no longer delegated to the transistor radio. Neither was the family car solely the domain of AM airwaves. Soon guys were sticking FM converters into their muscle cars. A new era of underground Album-Oriented Rock was born.

San Diego was no different. In fact, San Diego was a pioneer in this new incarnation of FM radio. By early 1968, San Diego’s KPRI, LA’s KMET, and the Bay Area’s KSAN were three of the first FM radio stations to adopt a free form, progressive rock format. Stations in NY, Boston, and Cleveland balanced out an even half dozen. By 1970, the “underground” FM radio would spread across the US.

In San Diego, radio historians will tell you that it was a Navy guy named Steve Brown (better known as the “OB Jetty”) who first tested KPRI’s progressive rock format. Brown, who went on to work for the Grateful Dead and as a DJ in the Bay Area, began broadcasting a midnight show while KPRI held to its mellower, “Capri by the Sea” song rotation during day. Soon, Brown expanded the “free form” format to 24 hours. KPRI was San Diego’s first FM station devoted solely to cutting edge rock ‘n’ roll.

By 1970, the hippie generation was growing up and it wanted radio DJs who reflected the gravitas of the times. Young people didn’t relate to the teeny boppers of the pre-Beatles era nor the AM DJs who guffawed and did circus stunts with their vocal chords after every song. The new FM DJs reflected a cool maturity. Instead of hooting and howling like on-air cartoon characters, the FM DJs mixed social commentary with hip, nonchalance and indifference, often remarking on the stark realities of contemporary American society: the Vietnam War, civil unrest, drugs. The new FM DJs were emulating George Carlin, Richard Pryor, Firesign Theatre, and Cheech and Chong, leaving the endless line of Wolfman Jack imitators on the AM dial.

In 1968, Gabriel Wisdom joined KPRI just as the station was adopting the new rock format. “I joined the station first as a sales rep,” Wisdom says. “Then one night, the DJ Captain Sunshine fell asleep. I got my big break and became the “fill in” guy. The FCC had a requirement that all radio stations had to feature some form of Sunday religious programming. So, I finally got a regular Sunday slot doing the ‘Joyful Wisdom Hour.’” During this hour, Wisdom would interview artists about spirituality, thus fulfilling KPRI’s obligation to the FCC. In all, he interviewed many of the rock stars and hipsters of the time, including Donovan, Jimi Hendrix, and Timothy Leary.

KPRI worked closely with San Diego’s big concert promoter at the time, Jim Pagni. So Wisdom emceed many of these shows including one Doors show when he was tossed off the stage by Jim Morrison. “He was the nicest guy backstage,” Wisdom recalls. “But when the lights went out and I introduced the band, this guy starts grabbing me.” It was Morrison trying to throw him into the audience.

Many of the bands, while on tour, would stop by the original KPRI studios at 7th Ave. and Ash St. “The bands would usually stay at the El Cortez,” Wisdom remembers. (The El Cortez was once the crown jewel of the San Diego skyline.) “It was only a couple of blocks from the hotel over to the studios. So, bands like the Who and Ten Years After would walk over during the day to visit.” Yet, for all of the fun and high jinx, KPRI’s mission had a serious aspect. “We thought what we were doing was important,” Wisdom says. “America had lost its way. We were promoting individual freedom, freedom of expression, and keeping government out of our lives.”

In the movie Almost Famous, fellow San Diegan Cameron Crowe paid homage to Wisdom, a long-time friend. The main character William, a knockoff of then-teenage Crowe ventures to KPRI’s San Diego studios to meet his idol and El Cajon, CA native Lester Bangs, who is also visiting the studio. The DJ is a woman named “Alice Wisdom.” The scene devolves into a vignette of “free form” radio as the Lester Bangs character throws records around the studio while Alice Wisdom tries to interview him. The idea of the “free form” format was really that there was no format. The DJ had carte blanche to let the music happen and allow any number of surprises or on-the-spot glitches to become part of the show. “We were free to make really good entertainment and really bad entertainment,” Wisdom says.

As 1960s counter culture morphed into 1970s counter culture, Hippie Nation became big business. Magazines such as Rolling Stone had already juxtaposed articles by Hunter Thompson with paid ads for Fortune 500 companies. The “back to the garden” ideals of pre-Woodstock were combined with doses of pragmatism and economics. Album sales were booming. Music had become the glue that held young people together. Record stores, concerts, musical instruments, home and car stereos. Ancillary businesses were popping up to cater to America’s rock ‘n’ roll culture. It was time for FM radio to “can the lightening.”

In 1972, a new FM upstart called KGB-FM was hatched in San Diego. The station had been owned since the 1950s by family-run Brown Broadcasting and had been bounced through the usual second-rate duties of early FM radio. The Browns also owned some AM stations and had originally tried to create an AM station with FM attitude. Finally, KGB-FM with a “frequency modulation” of 101.5 megahertz became one of the country’s first super-stations. KGB was quickly catapulted into the national spotlight and was an innovator of FM radio, winning many national awards.

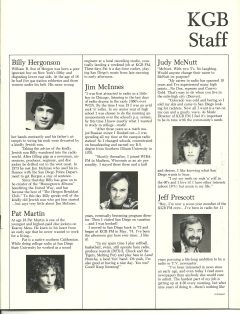

Locally, KGB was the prestigious station to work for, even when the pay wasn’t good. Many local radio and TV legends passed through the KGB ranks: Bob Coburn, Erik Thompson, Pat Martin, Bill Hergonson, Linda McInnes, Digby Welch, Brad Messer, Brent Seltzer, Pam Edwards, Brian Schock, Susan Hemphill, John Leslie, Andy Geller, Coe Lewis, and many others. Local musicians like Mojo Nixon and Country Dick Montana made regular on-air appearances. Local legend Larry Himmel worked for KGB. And many remember Cameron Crowe hanging out while in his teens. Crowe wrote the liner notes for KGB’s first two Homegrown albums.

KGB also perfected the morning drive team and rotated its many quick-witted DJs into that slot: Hergon Breakfast Club. Delany and Prescott, Berger and Prescott, the News Brothers and ultimately the morning team consisting of Dave Rickards, Shelly Dunn, and Cookie Chainsaw Randolph (DSC) would rule San Diego’s morning airwaves for 30 years. In fact, the DSC morning team has just moved back to KGB and continues to draw on the KGB brand of comedy that was started in the early days of underground FM radio.

One of KGB’s top DJs for 40 years, Jim McInnes moved to San Diego and joined KPRI in 1973. Within the year, he too was working for KGB. Soon, he would organize KGB’s first Skyshow in 1976. He would also co-produce KGB’s famous Homegrown albums from 1974 through 1984, all of which helped cement KGB as San Diego’s best FM radio station.

Ted Giannoulas, aka the KGB Chicken, joined KGB in 1974 and helped develop KGB’s signature brand of comedy. Smart yet wacky, the KGB Chicken was ubiquitous at rock concerts and sporting events throughout San Diego in the 1970s. For Giannoulas, the ’70s were a time for America to party after the serious tensions of the previous decade. It was a time to have fun and relax. The KGB Chicken created a one-man party everywhere he went. He was an updated version of Charlie Chaplin, a slapstick, silent comedian in a chicken suit, entertaining stadiums and arenas during the heyday of stadium and arena rock. It was absurd! Yet it was perfect. KGB’s instincts were correct again.

However, this party atmosphere does not mean the music suffered. In fact, the 1970s saw rock ‘n’ roll evolve (and devolve) into a complex array of sub-genres while it incorporated almost every other style of music, from classical to country to R&B to modern jazz. The FM DJ became America’s musical tastemaker. KGB was the place to hear the newest bands and albums. KGB was where you learned about upcoming concerts and when tickets went on sale. KGB provided the latest gossip about, and on-air interviews with, your favorite rock stars. In an era when rock stars were Gods, or at least pampered royalty, FM stations like KGB bought the rock star to life. This was before MTV and the internet. So it was FM radio that did the heavy lifting.

In this atmosphere, KGB launched the Homegrown album series, an annual compilation of songs about San Diego, written and performed by San Diego’s top artists. Sales, which some years approached 100,000 units, were donated to charity. And, as stated, Cameron Crowe wrote the liner notes for the first two albums. At a time everybody had a “record collection,” no local collection was complete without a couple, few Homegrown albums.

KGB reigned supreme in San Diego throughout the 1970s and 80s. Today, KGB is San Diego’s standard bearer of Classic Rock. And the KGB Sky Show remains synonymous with San Diego, drawing tourists from around the world. However, by the ’80s, Rock had split into various camps. FM stations such as 91X introduced a New Wave, post-punk format. Then, hip hop and country music began competing for Rock audiences. Ever since, the music market has become increasingly fragmented. Today, KGB is part of a stable of San Diego stations owned by iHeartRadio.

So why have I taken you on this Odyssean journey that started with the term “frequency modulation”? There must be some ulterior motive. Right? Of course, there is: My filmmaking buddies and I have the go-ahead to produce a film doc about 101.5 KGB-FM. We’re going to pepper it with backstory about early FM radio and look at the national impact of FM radio on America in the 1970s. But all in all (or “On and On” as Homegrown rejectee Stephen Bishop used to sing), this is going to be a movie about KGB 101.5 FM. The Sky Show, the Chicken, Gabriel Wisdom, JM in the PM, Berger and Prescott, the late Sue Delany, $1.01 concert tickets, the KGB van that roams San Diego looking for a parking lot near you. So gather up your KGB memories because we’re making a movie aptly titled KGB: The Station That Rocked San Diego. Check out the trailer for the documentary here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yCWqnaOrQNo