Yesterday And Today

Gerry Goffin: Beyond the Brill Building

Gerry Goffin and Carole King in a recent photo.

Goffin and King during their early days of songwriting

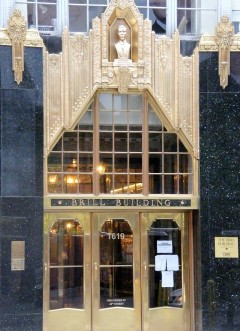

The famed Brill Building in New York City

It’s been said before in these pages, but like a great refrain, it needs to be sung once more, with a feeling: music is a form of prayer. It’s not a toy. It’s a talisman not to be trifled with, deserving of your utmost respect. It’s magical and mystical — a mysterious temple, capable of giving form to your dreams and the means for your aspirations to soar. When a really substantive piece of music reaches in and touches your heart, and provides you with whatever it is you need at that moment: solace, understanding, validation, wisdom, forgiveness, celebration — whatever was evoked by the intentions of the composer — music allows us to revel in the affirmation that we are alive in the here and now. It’s alchemy, pure and simple.

When a composition speaks to you and articulates something deep within, it becomes a part of your psyche, often to the point where you might even believe that you yourself wrote it — it conveys your depth of feeling to such a degree. That is what master tunesmiths do: they access that realm of universal feelings and express them for everyone to share.

If anyone in the course of twentieth-century popular music has been able to tap into that yearning for love and acceptance, of having the blues because you made a misstep, of feeling desire and being desirable, or wishing for an escape out of the boredom of circumstance and finding a safe haven in the arms of an unconditional lover — that person is Gerry Goffin. As the husband and songwriting partner of Carole King, Goffin is responsible for co-writing some of the most beloved songs of the last 50 years. He is a textbook example of taking your dreams to heart and sharing them with the world and finding out that you aren’t the only one who needs to be loved, or yearns to live in a world free of fear, bigotry, and hatred. It sounds like a fantasy of what heaven on Earth might look like, and Goffin expressed it time and again, frequently in less than three minutes and 33 seconds.

********************************

Gerald Goffin was born February 11, 1939, in Brooklyn, New York, and grew up in the borough of Queens. He graduated from Brooklyn Technical High School, enlisted in the Marine Corps Reserve, and spent a year at the U.S. Naval Academy before resigning from the Navy to study chemistry at Queens College.

It was at Queens in 1958 that Goffin met, and fairly quickly, married fellow student Carole King (she had already changed her name professionally from Carol Kline). They immediately started writing songs together, as Goffin told Vanity Fair in 2001: “She was interested in writing rock ‘n’ roll, and I was interested in writing a Broadway play. So we had an agreement where she would write the music to the play, if I would write lyrics to some of her rock ‘n’ roll melodies. And eventually it came to be a boy-and-girl relationship where I began to lose heart in my play, and we stuck to writing rock ‘n’ roll.”

By 1960 they were staff composers for impresario Don Kirshner’s Aldon Publishing at 1619 Broadway, otherwise known as the Brill Building: the most prestigious address in the world if you’re a professional songwriter. At Aldon they shared an office with another husband-and-wife songwriting team: Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil. The competition was fierce to produce a hit song for the recording artists of the day. At the urging of Kirshner, who was pushing for a “follow up” song for the Shirelles, after having a hit with “Tonight’s the Night,” Goffin and King unwittingly wrote a classic that defines the beginning of the 1960s: “Will You Love Me Tomorrow.”

As King wrote in her memoir, A Natural Woman, “my grandmother couldn’t understand how anyone could earn a living writing songs that appealed to teenagers, but that’s exactly what Gerry and I were doing. Though now in his twenties, Gerry hadn’t forgotten which three-letter word was foremost in the mind of every teen. It was s-e-x that kids thought about when they listened to lyrics about hearts full of love, hearts breaking, lovers longing, youth yearning, cars, stars, the moon, the sun, and that most innocent of all physical pastimes: dancing. We wouldn’t write a song about dancing until the following year, but sex was definitely the implied third character in our first big hit.”

When Goffin and King were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1990, writer Jon Landau summarized their significance: “As songwriters, Gerry and Carole stand as a great bridge between the Brill Building styles of the late ’50s and early ’60s, and the modern rock era. They started looking forward with their first hit [when] they wrote a ‘little’ song called ‘Will You Love Me Tomorrow.’ It was the first great ’60s record to be written from a woman’s point of view, and it was the first great ballad directed to a new generation that would soon be labeled ‘baby boomers.’

“In 1962, the Drifters recorded their sublime ‘Up on the Roof,’ a song that expressed the sensibility that a few years later would be called ‘sixties idealism.’ And in 1963, Gerry and Carole extended that idealism with the romantically eloquent ‘One Fine Day’ [by the Chiffons]. By the time they wrote ‘Don’t Bring Me Down’ for the Animals and ‘Goin’ Back’ for the Byrds, they helped to start an approach that would affect every singer/songwriter to come after them. And in a nice epiphany, in 1967 they closed the cycle they began with ‘Will You Love Me Tomorrow’ when they wrote ‘(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman’ for Aretha Franklin.”

The significance of Goffin and King’s music could not be more lovingly and succinctly put. These are the same sentiments this author heard from the podium in March of 2004, witnessing Goffin and King receive the Grammy Trustees Award from the Recording Academy for their “significant contributions, to the field of music.” It’s nearly as great an honor as John Lennon saying, in 1963, that he wanted Paul McCartney and himself to become “the Goffin and King of England.”

********************************

Over the span of several years, Goffin and King racked up one classic after another, including four number one hits: “Will You Love Me Tomorrow,” by the Shirelles; “Go Away Little Girl,” by Steve Lawrence; “Take Good Care of My Baby,” by Bobby Vee; and “The Loco-Motion,” by Little Eva.

If you listen closely to the lyrics that Goffin was coming up with to match King’s “rock ‘n’ roll melodies,” it is easy to hear the yearnings of someone who may have had it made on the material plane, but spiritually was yearning for something else.

“We should have been deliriously happy, and indeed, I was happy,” writes King. “In my bubble of contentment, I thought my husband was happy, too. But Gerry was beginning to feel the winds of the societal storm brewing on both coasts. That storm would become a tempest with enough momentum to polarize families across America and around the world.”

As King further shares in her autobiography, drugs unwittingly caused the partnership and marriage to unravel: “I don’t believe Gerry knew he was dropping acid the first time he ingested it. I believe someone who thought he was doing him a favor slipped it into his coffee. It wasn’t a favor. After that, Gerry took LSD many more times on his own. He lost touch with reality at first, for days, then for weeks at a time for many years afterward, with intermittent periods of lucidity, creativity, and wisdom. The appeal for Gerry and others who sought to ‘expand’ their minds was the notion that lysergic acid diethylamide would make them more creative and metaphysically aware. But people on acid found it difficult to communicate and function in a world dominated by people not on acid.”

Doctors diagnosed the 26-year-old Goffin as schizophrenic, then manic, treating him with massive amounts of Thorazine and eventually recommending shock therapy as a solution to his increasingly erratic temperament.

“When Gerry’s behavior started to become more irrational, I was afraid he’d do something he’d regret later. I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry when he climbed up on a ladder and painted “Love Your Brother” on the side of our house. However, when he attempted (and thankfully failed) to seriously hurt himself, I knew it was time to call for help.

“Shock therapy helped Gerry for a while in 1965, but the circumstances that led to his ingestion of LSD in the first place had not gone away.”

By 1967, Goffin was going through some serious changes. Tiring of the plasticity of life in the suburbs, he crafted a beautiful retort to the values of upward mobility in the Monkees #4 smash, “Pleasant Valley Sunday”: Creature comfort goals they only numb my soul and make it hard for me to see / My thoughts all seem to stray, to places far away / I need a change of scenery…

In Vanity Fair, Goffin later said that he “wanted to be a hippie — I grew my hair long, and Carole did it modestly. And then I started taking LSD and mescaline. And Carole and I began to grow apart because she felt that she had to say things herself. She had to be her own lyricist.”

The disconnect between the two writers is evident in some of the last songs they collaborated on, significantly, three of the tracks on the phenomenal 1969 LP by Dusty Springfield, Dusty in Memphis. “No Easy Way Down,” “Don’t Forget About Me,” and “I Can’t Make It Alone” speak directly to their circumstances and choosing to go their separate ways. And although the lyrics are credited to Toni Stern, Carole King’s 1971 smash “It’s Too Late,” appears to be addressing the dissolution of their partnership as well: It used to be so easy living here with you, but we just can’t stay together don’t you feel it too, still I’m glad for what we had, and how I once loved you.

They divorced in 1968. Both went on to continued success as individuals with King having a successful run of hits during the ‘70s, including the definitive singer/songwriter LP of the era, Tapestry. Goffin released a solo album of his own in 1973, It Ain’t Exactly Entertainment, and continued to write lyrics into the ’90s, enjoying two number one songs with composer Michael Masser: the Oscar-nominated, “Theme from Mahoghany (Do You Know Where You’re Going To)” by Diana Ross, and “Saving All My Loving for You,” by Whitney Houston. Another of his great songs from the 1970s, written with Barry Goldberg, is “I’ve Got to Use My Imagination,” a top 10 hit by Gladys Knight and the Pips. This song also addresses the pain of a breakup: I’ve really got to use my imagination to think of good reasons to keep on, keepin’ on / Got to make the best of a bad situation, ever since that day, I woke up and found that you were gone…

********************************

Goffin passed away June 19, 2014, in Los Angeles, California, at the age of 75. The Guardian referred to him as “the poet laureate of teenage pop.”

In 1975, Goffin told writer Bruce Pollock: “I can’t write under deadlines anymore, but I respect people who can. Right now I’m just writing what I feel like writing and I keep changing. If I want to write something commercial, I don’t see anything wrong with it. If I want to write a song that I feel personally, I don’t see anything wrong with that either.

“I’ve written a couple of thousand songs. I write a lot more songs that people don’t use — about 50-to-one. Last year I wrote 40 songs in 40 days.

“There’s also another thing. There’s a certain magic that some records have and that some records don’t have and that’s not a quality you can capture unless everything is going right. There are so many personalities involved, so many variables. Sometimes you can write a mediocre song and it becomes a big hit — it’s really hard to talk about.

“I’m not going to say whether my songs were good or bad. If people like them, that’s fine and I’m happy. You’ve got to realize when I started writing songs there’s been several revolutions that have taken place in pop music, and I think they were all improvements. I’ve always thought, any way you looked at it, the changes have been for the better.”

In a statement, Carole King said: “Gerry Goffin was my first love. He had a profound impact on my life and the rest of the world. Gerry was a good man and a dynamic force, whose words and creative influence will resonate for generations to come. His legacy to me is our two daughters, four grandchildren, and our songs that have touched millions and millions of people, as well as a lifelong friendship. He will be missed by his wonderful wife, Michele, his devoted manager, Christine Russell, his five children, and six grandchildren.”

GOFFIN/KING COLLABORATIONS

Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow?/The Shirelles (11.60)

Take Good Care of My Baby/Bobby Vee (08.61)

Some Kind of Wonderful/The Drifters (03.61)

Every Breath I Take/Gene Pitney (08.61)

Don’t Ever Change/The Crickets (1961)

Chains/The Cookies (11.62)

Keep Your Hands Off My Baby/Little Eva (11.62)

The Loco-Motion/Little Eva (06.62)

He Hit Me (It Felt Like A Kiss)/The Crystals (1962)

Go Away Little Girl/Steve Lawrence (11.62)

Point of No Return/Gene McDaniels (08.62)

It Might as Well Rain Until September/Carole King (05.62)

Up on the Roof/The Drifters (06.28.62)

Don’t Say Nothin’ Bad (About My Baby)/The Cookies (03.63)

He’s a Bad Boy/Carole King (04.63)

I Can’t Stay Mad at You/Skeeter Davis (09.63)

Hey Girl/Freddie Scott (07.63)

One Fine Day/The Chiffons (06.63)

I Can’t Hear You No More/Betty Everett (09.64)

I’m into Something Good/Herman’s Hermits (10.64)

Oh No Not My Baby/Maxine Brown (10.64)

Just Once in My Life/The Righteous Brothers (1965)

Some of Your Lovin’/Dusty Springfield (196?)

Don’t Forget About Me/Barbara Lewis (01.66)

Don’t Bring Me Down/The Animals (05.66)

Take a Giant Step/The Monkees (10.10.66)

Sweet Young Thing/The Monkees (10.10.66)

Sometime in the Morning/The Monkees (01.10.67)

Goin’ Back/Dusty Springfield (07.66)

Pleasant Valley Sunday/The Monkees (07.10.67)

Star Collector/The Monkees (11.06.67)

(You Make Me Feel Like) a Natural Woman/Aretha Franklin (1967)

Porpoise Song/The Monkees (1968)

I Wasn’t Born to Follow/The Byrds (1968)

That Old Sweet Roll (Hi-De-Ho)/The City (1968)

So Much Love/Dusty Springfield (03.31.69)

Don’t Forget About Me/Dusty Springfield (03.31.69)

No Easy Way Down/Dusty Springfield (03.31.69)

I Can’t Make It Alone/Dusty Springfield (03.31.69)

Smackwater Jack/Carole King (1971)

Let Me Get Close to You/Alex Chilton (1987)

COLLABORATIONS WITH OTHER ARTISTS

Oh Neil/Carole King (1959) Greenfield, Sedaka, Goffin

Who Put the Bomp (in the Bomp, Bomp, Bomp)/Barry Mann (1961)Â w/ Barry Mann

How Can I Meet Her?/The Everly Brothers (1962) w/ Jack Keller

Yes I Will/The Hollies (1965) w/ Russ Titelman

I’ll Meet You Halfway/The Partridge Family (1971) w/ Wes Farrell

I’ve Got to Use My Imagination/Gladys Knight & The Pips w/ Barry Goldberg

Theme from Mahogany/Diana Ross w/ Michael Masser

Saving All My Love for You/Marilyn McCoo and Billy Davis Jr. + Whitney Houston w/ Michael Masser

Tonight, I Celebrate My Love/Roberta Flack & Peabo Bryson w/ Michael Masser

Miss You Like Crazy/Natalie Cole w/ Michael Masser & Preston Glass