Tales From The Road

Justin Townes Earle: “Tryin’ to Move On”

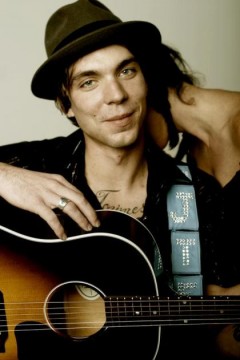

Justin Townes Earle

“Thirty years of running has left me standing with my back to the cold, and it’s left me most days wondering if I’ve ever really learned a thing at all. But I’m trying to move on.”

– Justin Townes Earle

In 1986 when singer-songwriter Steve Earle released his now-classic, Guitar Town, he closed out the album with the song, “Little Rock ‘n’ Roller” for his four year-old son, Justin Townes Earle. Since that time, there has been a lot of hard road traveled beneath the now 30-year-old JT Earle’s shoes. Carrying his family name is enough of a burden in becoming a young artist in shadows and high expectations. However, for Steve Earle, the family name wasn’t enough. So, he gave Justin the middle name Townes, after Townes Van Zandt, the legendary Texas singer-songwriter who was a mentor and friend to the elder Earle. Townes was bent on a path of self-destruction while creating some of the most lyrically poetic and vital American music of the ’80s and ’90s. More than 15 year after Van Zandt’s alcohol-related death, he is today regarded a near saint in the Americana music world. But, JT Earle takes the name in stride, self-effacingly saying, “Anyone who tries to live up to Townes Van Zandt is a fool. I’m honored to carry the name, but if I spent my life trying to live up to it, I’d have a pretty miserable life.”

Fortunately, as fate would have it, Justin Townes Earle does live up to his heart-worn pedigree and his auspicious middle name. With four albums and one EP in release since 2007, Earle has just released his first album as a producer of the timeless and seemingly ageless rockabilly queen Wanda Jackson’s latest, Unfinished Business.

His earliest releases were like the first steps of a soon-to-be brilliant songwriter. It was clear, as he developed, the world of Americana music would be listening. After touring and playing in his father’s band, he learned his stage craft well. During the ensuing years he has developed a stage persona that plays like a patchwork enigma with tiny visions of Elvis Costello, Pee Wee Herman, and Jim Caroll, whose memoir, Basketball Diaries, was the basis for his award winning song, “Harlem River Blues.” In all of this, what makes the cultural cocktail mix work so well is the absolute certainty and authenticity of his work, live and on record. He has come to this unique place hitting a core nerve in his creative self that neither emulates nor imitates, but authenticates the process of discovery through the artistry of the song. This is best embodied in 2010’s album, Harlem River Blues, and 2012’s Nothin’s Gonna Change the Way You Feel About Me; albums that easily stand alongside Steve Earle’s Guitar Town.

But, the life-lessons that have led him to this creative peak have not come without costs. At 30, he has also walked along the same gravel roads of his often self-destructive mentors. Some will argue that Earle was hard-wired for addiction with a genetic code long written in the life his father. By his 20s, he found himself struggling with a 10-year drug and alcohol addiction. Indeed, throughout his first decade of performing he has always been candid bout this battle. However, within days after the release of Harlem River Blues in September of 2010, reports came in that he had an emotional melt-down following a show that included a heckling audience in Indianapolis. While he barely contained himself during the show, when he arrived backstage he reportedly went wild with rumors of assaulting the venue’s manager and his daughter. The result was a night in jail.

Following some reflection and the sage advice his professional support system, Earle cancelled a tour in England. In the days immediately following his arrest he binged himself into an emotional tail-spin with the help of daily eight-balls of cocaine and a half-gallon of vodka. After six years of sobriety and carefully built career success, his feelings of failure where overwhelming. They soon turned into acute paranoia over reports that he had hit a woman during his Indianapolis tirade. “I’d just be walking down the streets in Manhattan thinking everybody was looking at me,” Earle told AP reporter David Bauder in October of 2011. “I thought everybody knew about what happened and it absolutely was just crushing me. I remember vaguely calling my publicist at the time — I fired my manager not long before that had happened, and my publicist and my booking agent were the only people still working for me — and [I was] just hysterically crying and saying I just didn’t want to do this anymore. I didn’t want to tour any more. I didn’t want to make records.” Soon after this Earle entered his 13th visit to rehab.

While the 30 days of rehab. grounded him and got him back on the road and into the studio, success was limited with a major relapse to heroin. Eventually, he settled into a program of marijuana maintenance and was given an anti-addiction medication called Soboxone. Today, he has remained clean and sober from heroin and alcohol abuse for more than a year. “I looked back and realized there were a lot of questions as to whether I’d make it out of my 20s. If you die in your 20s, you get tribute records. If you die in your 30s, you’re just stupid,” he told the Daily Beast last March. “I definitely saw [my birthday] as me needing to get rid of the myths that I’d been living for a long time… the myths of the tortured musician.”

If his early records found himself restless in the shadow of his father, working to define his own voice, his last two albums have defined a career that is growing both in style and substance. He recorded Harlem River Blues while addicted to heroin. With the obvious inspiration from the Basketball Diaries, the title song ironically speaks to a desire for drug-induced suicide. But, the top soil of the layered theme is an unholy baptism. “Lord, I’m going uptown to the Harlem River to drown/Dirty water gonna cover me over and I’m not gonna make a sound.” This is echoed in his past descriptions of his heroin relapses as “vacations in the ghetto.” Yet, the underlying tone of the majority of the album, especially the title song, is more of a baptism in early American gospel. The album is built on a stripped down live-in-the-studio feel with clear influence from mid-period Tom Waits. This can be heard in “One More Night in Brooklyn,” and “Christ Church Woman.” Other key tracks are “Roger’s Park” and “Learning to Cry.” The entire album echoes the early ’70s reflections of the singer-songwriter movement. But, it’s the fresh look and the constant hopeful voice embedded in these songs that draws us in to his world. Still so young and even through the eyes of the tenacious demon we call addiction, there remains a youthful sense that just around the corner life will be better.

As he moved through the gospel roots of Harlem River Blues, Earle takes things a step further with a natural progression to a Memphis soul sound on his fifth album, Nothin’s Gonna Change the Way You Feel About Me. The feeling on this album is like he’s stepped out from the Harlem suicide sanctuary into the light of day, and the clarity of that light is not always comfortable. But, the growth he shows as an artist is not only in the sound of Memphis guitars and horns. It’s also in the lyrical themes he confronts. The album opens with words about his dad; “Hear my father on the radio singing ‘take me home again’/three hundred miles from the Carolina coast and I’m skin and bones again. Sometimes I wish I could get away/sometimes I wish he would just call/Am I that lonely tonight/I don’t know.” This opening track confronts both his relationship with his father and, ultimately, himself.

The remainder of the album moves with a relaxed ease through songs of cruelty (“Look the Other Way”), broken relationships (“Nothing’s Gonna Change the Way You See Me,” “Maria”), and acceptance (“Won’t Be the Last Time). Two of the final tracks, “Memphis in the Rain” and “Movin’ On,” bring a sense of renewal and clarity to the table. Within all of this, the celebration of the Memphis sound provides a soulful foundation for each song. “Movin’ On,” returns to his opening father-theme, still singing from the road as though his clearest memory of his father is his absence. It describes an ordinary moment in a life finding recovery from drugs and alcohol. But, his story isn’t the typical one of total success. Rather he says, “I’m tryin’ to move on.”

These two albums are clear reflections of Earle’s life coming through the pain of addiction. Harlem River Blues finds Earle midstream, reaching for hope in the midst of a raging flood while Nothin’s Gonna Change the Way You Feel About Me finds him clear-eyed confronting many of the painful feelings that come up in sobriety. As has been said in the past, “there’s no pain like sober pain.” Earle has been generous in allowing us into that discovery through his music and the candid nature of past interviews. His young life has been like a fast-track through the pitfalls of success and addiction. As he continues, he brings with him the ghosts of his mentors in his music and his experience. If Townes Van Zandt were looking down from songwriter heaven, it’s hard to not imagine a gentle smile on his face when he hears the music of Justin Townes Earle. Indeed, this artist has lived up to his pedigree and his name-sake and then some. Indeed, he may even be able to move beyond them. We certainly hope so.

See Justin Townes Earle on Wednesday, December 12, 9pm, at the Belly Up Tavern, 143 S. Cedros, Solana Beach.