Yesterday And Today

PASSION PERSONIFIED — Getting Your Kicks and Expressing Yourself: THE SAN DIEGO ZINE EXPLOSION

Passion: [noun] A powerful emotion, such as love, joy, hatred, or anger. Ardent love. Strong sexual desire; lust.

Q: What motivates you to do the things that you do in this life, borne out of “necessity,” “responsibility,” or “choice?”

And beyond the daily grind of fulfilling those responsibilities, how else do you choose to spend your hours and days? Do you engage in activities that feed your spirit and fill you with joy? Because bliss is certainly something to value, with the inadvertent byproduct resulting in the beatitude of gratitude for simply being alive.

What I’m really talking about is passionate connection: that rush of adrenaline that you get from loving something so much that it almost hurts to feel — THAT’s how much emotion you have for that particular person, place, or thing. I mean, what would make a Jehovah’s Witness minister for their faith door-to-door, with a grassroots magazine (Awake!) cradled in their arms, in order to spread the good word about an idea that they’ve become so passionate about that they just HAVE to let other people know ALL about it? That is fervent passion.

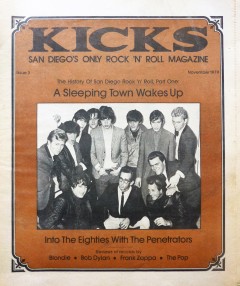

When we identify with something so strongly, be it soccer, craft beer, or even needlepoint, we frequently want other people to share in that excitement (perhaps because it makes us feel like less of a freak for our obsessive habits). In San Diego’s long and storied musical history, the landscape has been inundated with passionate tracts from all over the county. However, very few publications have waved such an impassioned banner for San Diego music the way Kicks magazine did between September 1979 and March 1981.

The magazine was the brainchild of native San Diegan Thomas K. Arnold — a self-proclaimed nerd at University of San Diego High (now Cathedral). “I had big, horn-rimmed glasses,” says Arnold. “Do you remember “It’s Pat” from Saturday Night Live? I kind of looked like that. But during my high school years I learned about rock ‘n’ roll and began writing a column for my school paper in my junior year. And all of a sudden, I was Mr. Popularity. I was the rock critic, the guy who went to rock concerts. And this was when punk and new wave music began to happen.

“I was one of those guys who, at 17, would go to Licorice Pizza in Pacific Beach every week and pick up copies of Billboard, CREEM, Circus, and Rolling Stone,” he says. “I really educated myself about music. And through my writing, I was able to get on PR lists for a number of different record companies. I still remember getting the first Ramones album in the mail and hearing the Stranglers for the first time. After being brought up on Journey and Kansas and Heart and all of those sound-alike bands, hearing that kind of music was a real eye-opener.

“And then things started happening in San Diego — I remember seeing the Dils at Glorietta Bay [in Coronado]: it was one of the first punk shows with local bands. Hearing these wild sounds and seeing all of these people was a real awakening for me. Through the Ramones and the Sex Pistols, I was already familiar with this kind of music and this type of energy, but it really started taking off in San Diego in the late ’70s.

“I saw a magazine called BAM — Bay Area Music up in San Francisco, and I decided that I could do this here in San Diego. With absolutely no market research or funding, I said, ‘I’m going to do a music magazine, and it’s going to be half national and half local.’ In the era before the Internet, we had a free bulletin board for musicians booking or seeking gigs: that was a very popular feature in the magazine. And at the same time we started seeing a lot of clubs spring up.

“I launched the magazine in August 1979, and that summer and fall is really when things began to take off. We saw bands like the Penetrators, and Rick Elias. We saw the Skeleton Club, the Spirit Club, the Zebra Club: it was an incredibly productive and creative time here in San Diego.”

Borrowing their masthead slogan from CREEM magazine (“San Diego’s Only Rock ‘n’ Roll Magazine”), Kicks transcended the great divide between grassroots underground reportage and corporate conventionality. It was a place where fans of the Buzzcocks could also hang out with fans of Aerosmith — at Kicks there was room for everybody. And they did it with a fervor that was intoxicating to the local congregation.

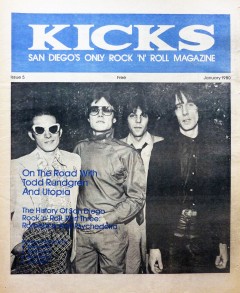

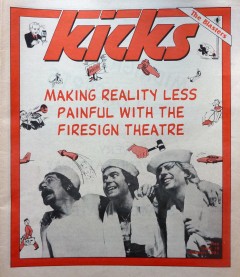

During its run, Kicks featured extensive coverage on scores of local San Diego bands like DFX2, the aforementioned Penetrators, Jerry Raney & the Shames, Rosie and the Screamers, the Puppies, and the all-female Dinettes. But also in the mix was a curious blend of AOR arena rock (Peter Gabriel, Blue Öyster Cult, Pat Travers, Rick Derringer, and Todd Rundgren’s Utopia) rubbing shoulders with representatives of the up-and-coming new wave and punk scene (Gary Numan, Talking Heads, Devo, and X). Hell, they even had the good taste to put surrealist humorists Firesign Theatre on the cover of their penultimate issue in February 1981.

But perhaps the boldest stroke of coverage Kicks provided was a whopping FIVE-part history of San Diego rock ‘n’ roll by Troubadour contributor Steve Thorn, which included a hand-drawn Family Tree (Ã la Pete Frame) of the incestuous San Diego music scene by none other than Dan McLain (aka Country Dick Montana).

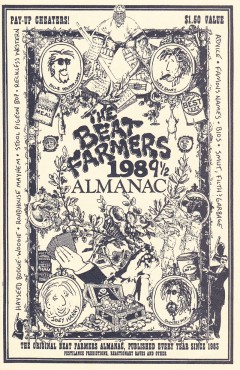

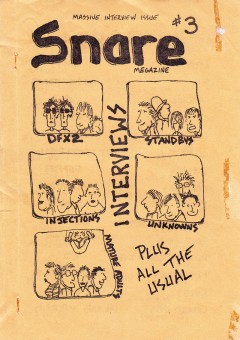

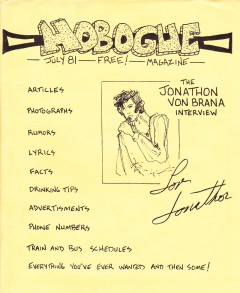

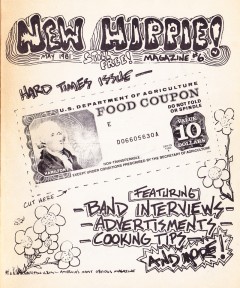

“I can’t imagine the San Diego music scene without the efforts of Dan McLain,” says musician David Fleminger. Between the irreverent, humorous fanzines that he produced (Snare, New Hippie, Hobogue, The Weekly Dirtbag, The Beat Farmers Almanac); performing in the Penetrators, Crawdaddys, and Beat Farmers; independently promoting concerts; and running his own record store (Monty Rockers); McLain pretty much single-handedly created the San Diego music “scene.”

The list of writers who cut their teeth at Kicks magazine are also primary to San Diego music culture, boasting a masthead that included: George Varga and Mikel Toombs (both of whom went on to careers at the San Diego Union-Tribune); professor Steve Thorn; Barry Alfonso; Clyde Hadlock; and the incredibly mean-spirited Stephen Esmedina (regarding Janis Joplin, he once scrawled in the Reader: “the deep-sixing of that screeching lush was a welcome deletion.”).

If anything, Kicks has proven to be an invaluable time capsule, when regionalism still ruled and San Diego was a vague blip in the national consciousness. After producing 19 issues of the magazine, and building a circulation of 20,000 readers, Kicks stopped production in the spring of 1981 when Arnold decided to take over the management of faded ’60s pop vocalist Gary Puckett.

Arnold: “I would be up until two in the morning getting the magazine ready, and then the next day go out and try to collect money to pay the printer bill. We had some months that were better than others, but when the ads slowed down with the coming recession of 1980—81, I started to lose money and I couldn’t afford to do that.

“Kicks was always a shoe-string operation; I got people to help out, but unless you pay people real salaries it’s hard to find the passion. At the same time I had become friends with Gary Puckett. So I basically handed the magazine off to my former managing editor Albert Carrasco and took Gary Puckett on the road with a new band, and got him back in the studio. Albert sat out an issue, which is a bad thing to do in publishing, and then the magazine just died after that.

“But that was a very interesting period in San Diego music history. The late ’70s/early ’80s wasn’t a good time financially — this was right before CDs and vinyl was starting to peter out. But musically, it was a creative, flourishing period.”

*****************

Since 1851 there has been a traditional, broadsheet newspaper in San Diego County, starting with the San Diego Herald (1851-1860) and the San Diego Sun (1861-1939). These days, most of the county relies on the U-T San Diego for its daily reportage, ever since the San Diego Union (1868-) and the San Diego Evening Tribune (1895-) merged forces in 1992 and re-branded itself as the U-T San Diego in 2012. But what kind of mouthpiece is the U-T San Diego?

In theory, newspapers are supposed to objectively report events as they occur in the world, instead of becoming a propaganda platform for special interests and business lobbying. When entrepreneur John Lynch and the Manchester Group took ownership of the U-T San Diego in 2011, Lynch stated on KPBS radio that he and Manchester “wanted to be cheerleaders for all that is good in San Diego. We make no apologies. We are doing what a newspaper ought to do, which is to take positions. We are very consistent — pro-conservative, pro-business, pro-military. And we are trying to make a newspaper that gets people excited about this city and its future.”

That, in a nutshell, is the double-edged sword of the press and the media in general. Without the resources to counterbalance big business and a “pro-military” stance in the world, this is what the general population ends up with, by default, as their version of truth in the world. Whatever your political stance might be, the U-T San Diego has consistently been a poor excuse for killing trees, with its increasingly milquetoast content coming perilously close to pablum (not to mention openly pushing a rather odious political agenda).

I neither condemn nor advocate the San Diego Reader or Citybeat magazines, but their additional viewpoints succeed in offering a slightly broader perspective that keeps the neo-conservative agenda of the U-T San Diego somewhat in check. However, at the end of the day, it’s all about making money, as the advertising that drives both weeklies demonstrates the type of culture that we continue to perpetuate, with countless ads offering Botox and liposuction treatments, real estate brokers, marijuana dispensaries, and phone sex/escort services. Why is it that so many media outlets champion the lowest common denominator? Is this the best we can do to entertain and inform a metropolis of three million people in 2015?

It all boils down to resources and what you wish to perpetuate in the world. Thank goodness that beyond the broadsheets of crony capitalism there have been brief, but potent periods, when true alternative viewpoints were heard in San Diego. Between 1968 and 1975 San Diego sported a radical series of underground magazines: the Free Press/ Street Journal (between November 1968-December 1970); the San Diego Free Door to Liberation (January 1968-1974); and the O.B. Rag (1974-1975).

It was a time of bold proclamations: It’s time we said it loud and clear: San Diego is the armpit of the world. This town is middle class, stupid, mediocre, and boring. It is plastic, sterile, unhip, and sexually repressed; it is also militaristic, racist, exploitive, and arrogant. In short, it is both a drag of a town and a fascist town. Solid citizens of San Diego, you’ve had it; the next 200 years are ours. – San Diego Free Press editorial, January 1, 1969

Can you imagine such sentiments being written about our fair city today? And is any of this “Yippie” rhetoric relevant to contemporary San Diego?

*******************

The power of the press has demonstrated since time immemorial how consciousness and public opinion can be swayed by a well-written editorial or exposé. Pulitzer Prize-winning The Washington Post reporters Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward managed in 1974 to topple the Nixon presidency through their investigative efforts, and that is one small example of how powerful the Fourth Estate can be in shaping our perception of the world that we live in.

But what about the passionate enthusiast who isn’t necessarily interested in political reform? Who, rather, is interested in fomenting a cultural revolution or creating an alternative community? For decades, western culture (i.e., rock ‘n’ roll) was outlawed in communist countries such as the former U.S.S.R. and China, largely because of the ideas contained within promoting life, liberty, freedom of personal expression, and the ability to forge your own destiny without impedance from the state. It’s absolutely true — music, literature, film, and the fine arts can alter the destinies of individuals and nation states. And it is the passion contained within those disciplines that often finds an expression in the unlikeliest of places — such as a rock ‘n’ roll fanzine.

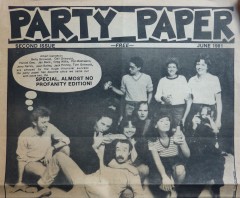

In addition to Dan McLain’s work that began in the late 1970s and continued until his untimely death in 1995, there have been many memorable publications produced out of San Diego over the years. In the ’70s there was Tom Griswold and Jacki Ramirez’s Substitute; Mikel Toombs’ Quasi-Substitute; and the anonymous art collective Cabaret Voltaire. In the ’80s there was Slax, Harold Gee’s Party Paper, Steve Gardner’s Noise for Heroes, and Terry Marine’s Be My Friend. In the ’90s there was Trevor Watson’s Revolt in Style, John Chilson’s Schlock, Andy Rasmussen’s Fuck Yeah!, John A. Rippo’s The Espresso, and Steve Garber’s The Poetry Conspiracy. All of these publications (and many more) serve as excellent examples of fandom at its finest, exemplifying the spirit of fanzine creation that serves as both PR mouthpiece and cultural manifesto.

Although not originally a San Diegan, the unquestionable granddaddy of rock ‘n’ roll fanzine publications is Paul Williams, who started his Crawdaddy! [The Magazine of Rock] newsletter in January 1966; influencing countless other writers and publishers to express their ideas with a similar passion. (For a comprehensive history of Williams’ career check out the May 2013 cover story in the Troubadour.)

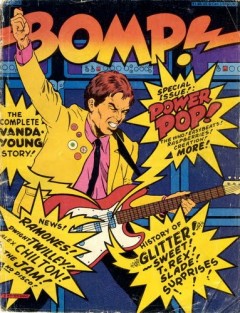

The example that Williams expressed with Crawdaddy! set the template for others to follow, including Jann Wenner at Rolling Stone and, more important (in terms of pure rock fandom), Greg Shaw, who published well over 300 fanzines in his lifetime (1949-2004). Shaw’s publication Who Put the Bomp? became THE template for how a fanzine should operate, with a viewpoint that was unswervingly opinionated, passionately aiming to turn each and every reader into a fellow comrade in the cultural crusade of the rock ‘n’ roll revolution.

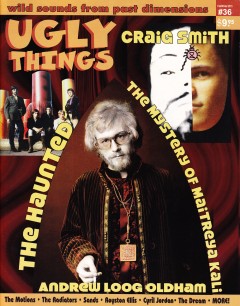

However, the distinction of the longest running, best produced, and most consistently published fanzine in San Diego County belongs to Mike Stax and his bi-annual publication Ugly Things (with the subtag “Wild Sounds from Past Dimensions”). A native of Great Britain, Stax came to San Diego in November of 1980 to play bass in the garage/psyche band the Crawdaddys, and within a couple of years that sensibility and passion for the music and culture of the 1960s began to express itself in the pages of Ugly Things. And it was Shaw’s example that led the charge. “Even though Greg could be wrong at times, he put his opinions out there,” says Stax. “And that’s what fanzine culture is like.”

In drawing the distinction among fanzines, prozines, and magazines, Stax offers up this assessment: “There are kind of fuzzy boundaries between each one, but I’ll list a sort of hierarchy of evolution. I would say that a fanzine is completely fan generated: not-for-profit. It may not even carry advertising. And there isn’t necessarily a plan beyond producing one or two issues. A fanzine often evolves into a prozine. A prozine would be a fanzine that is now able to support itself somewhat or at least supplement its income with some advertising, and perhaps envisions going beyond a few issues to be an ongoing publication. It’s a fanzine that has found an audience and, along with that, a chance to increase circulation. A prozine would be more widely distributed outside of its own region, and is able to pay for itself or at least supplement itself.

“A professional magazine compartmentalizes the elements of publishing. There is probably an advertising department. There is a department in charge of distribution and a team of people who are in charge of creating content. So, it’s become a company. It’s entered the mainstream, it’s on newsstands, it’s in Barnes & Noble and all the big bookstores. The advertising is ongoing and lucrative, and driven by income, because it’s supporting a number of people for their jobs. So it’s a professional magazine at that point.

“I haven’t really reached a magazine stage, though I do have wide, international distribution. Ugly Things does generate enough income to support me, but not a team of people. Everything is still handled in a fanzine way because I sell the advertising. I’m in charge of the advertising, I interact with a number of distributors; there isn’t a distribution company or a publisher that is publishing it for me — I am the publisher. I’m obviously responsible for the content — but I am also helped by a staff of unpaid writers. I’m a prozine that brushes along the bottom edges of the professional magazine world. [laughs] Chasing that, but not necessarily wanting it, because I think once you achieve that magazine thing you’re answering to your ‘evil overlords.’ Not necessarily evil, but you’re answering to a publisher; you’re answering to the people who are selling advertising, who are going to demand that your content helps out their advertising sales.

“I don’t have that situation. I’m wholly independent, even though I have to keep my subscribers and my advertisers happy. That’s another thing we should talk about: subscribers. Certainly a fanzine would not have subscribers, it would just be sort of hand-to-hand or sold in a record store or sold at shows. A prozine would maybe have a subscriber list, and a magazine would certainly have subscribers. And a magazine would also have to have a clockwork-like schedule. A prozine, not so much, and a fanzine, not at all.

“The first issue of Ugly Things was produced in March of 1983 and the production was kind of willy-nilly. Around issue #13 it started to have better binding, a glossy cover, steady advertising revenue, and the printing was in the thousands at that point, rather than the hundreds. So at that point maybe I was a prozine, but I still think of Ugly Things as a fanzine. Proudly. But it’s a professional fanzine, more professional than most fanzines, I suppose.

“At the same time I started doing Ugly Things, John Hanrattie [of the Gravedigger V] did a Rolling Stones fanzine called December’s Children; I think he did maybe three issues. It was basically all about 1960s Rolling Stones. Because we both worked at the College Copy Center by SDSU,” he chuckles. “There was sort of a fanzine revolution going on out of there. And after December’s Children, he had one called Toffee Sunday Smash!, which was all about U.K. psychedelic music from the ’60s. That had a couple of issues and that’s kind of a cult fanzine now: people are looking for those. So, that was important to me and our ’60s scene. There was Ugly Things, December’s Children, and Toffee Sunday Smash! — all coming out of the same copy shop!”

****************

With the long lens of 30+ years to look back through, U-T San Diego pop music critic George Varga has this to say about his Kicks experience: “Kicks did very well for a free monthly, music zine, and it looked much better than many other, bigger publications, thanks to the excellent layouts by art director Ted Meyer. That it lasted as long as it did, with just a few paid staffers and a lot of unpaid freelancers, is remarkable. So is the fact that Kicks secured interviews with everyone from Talking Heads and the Ramones, to Pat Benatar and Yes, all of whom were featured on the cover. The staff included some of the best music writers in town, including Ted Burke and Joel Dinerstein, who preceded me as editor.

“At the start, Kicks co-founders Tom Arnold and Albert Carrasco had no magazine, no office, no phone lines, nothing, except the ‘Kicks publisher’ nameplates for the desks that they also didn’t have yet. They would take these nameplates to parties and show them off. That they were able to get Kicks up and running for as long as they did is a testament to their vision.

“Tom called me one night to say he was leaving Kicks to manage the ‘comeback career’ of Gary Puckett. I asked him, ‘Tom, what happens if Gary Puckett drives off a cliff, and I mean that figuratively, not literally?’ Tom responded that nothing could go wrong, then stole Billy Thompson, the lead guitarist from the Fingers, for Puckett’s band. That band, and Puckett’s ‘comeback,’ was history within two months, as was Tom’s music management career. Kicks continued, but without Tom as a driving force, the magazine begun its slow death spiral.

“It was a lot of fun and a great learning experience, and I hope some kids here will put together their own Kicks soon.”

It’s a beautiful idea and perhaps unlikely, as the Internet and the world of web blogs has, in turn, changed much about the world of publishing. David Stampone’s recurring feature in the Reader “Zine Envy,” or a magazine such as Factsheet Five that chronicled the fanzine revolution at its height of popularity during the ’80s and ’90s, no longer seems to be as relevant as it once was. And yet, every generation is ripe for staging a revolution, and there’s something to be said about expressing yourself in print, and to be able to hold an art object with your own two hands: an object that doesn’t merely exist as a hologram in cyberspace. A well-produced fanzine can change the world — all it takes is a vision, and the creative energy to express a vitalizing point-of-view, and LOTS of passion. Art is funny that way.