Featured Stories

SONO Fest: Eat a bowl of Chili!

“It feels less like a street fair and more like a party.” Brijet Meyers, SoNo Fest Chairperson, is explaining the annual chili cook-off that comes around on Sunday, the 5th of this month. “It’s unique. It’s intimate, not overproduced. It’s a community event, and you’ll see your neighbors there.”

This year marks the 12th year of the SoNo Fest. Besides celebrating one of America’s favorite dishes, the event raises money for McKinley Elementary, the neighborhood school. As in years past, four blocks of Thorn Street, around the intersection of Thorn and 32nd, will be dedicated to arts and crafts, a full beer garden, two stages with live music, and lots and lots of chili.

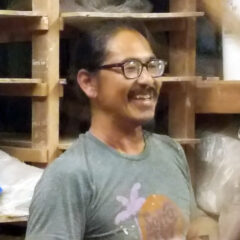

Kouta Shimazaki, one of the organizers of the event, says that there is a neighborhood chili cook-off on Saturday, where neighbors and friends bring their chili for tasting and to compete in the differing categories of chili: meat chili, vegetarian chili to name a few. As a potter and pottery instructor, Shimazaki and his students make ceramic bowls for the yearly cook-off. “On Saturday, you can buy a bowl and have as much chili as you want!” he says.

Sunday is the big day, the day with music, crafts, and restaurant competitions with their chilis. Nearly 30 restaurants will be taking part this year, including entries from Fernside, Ponce’s Mexican Restaurant, and The Rose. The beer garden features local brews, such as Fall Brewing, Mike Hess Brewing, and North Park Beer Company. Besides the chili and beer, the festival includes a food truck court. SoNo Fest is presented by McKinley Elementary PTC and San Diego Ceramic Connection.

Most of the restaurant chefs make a traditional chili, with beans and beef. But there have been some interesting variations. Underbelly, the Asian themed restaurant, came up with a chili made from duck. There have been island rice chilis, and chilis that feature locally harvested fish. One year, Japanese curry chili was an entry. The bowls that Shimazaki and his students make are large enough for a two-ounce taste; $25.00 gets you five tastes and you get to keep the bowl.

“The focus is on South Park, so the restaurants in that neighborhood are who we reach out to first,” Meyers says. “But a lot of other restaurants have been eager to join in. Some of the restaurants who have been with us from the start are Panama 66, Blind Lady Ale House, Bivouac, and Big Front Door.

“We always feature local bands. But most of all, it’s a fundraiser for McKinley. Without fundraisers for the school, there would be no art, music, or language instruction for the kids. Due to the pandemic, last year’s event was online. Still, we were able to raise $15,000 for the school.”

Try to find somebody who doesn’t love chili. You won’t. Along with spaghetti and meatballs, tacos from taco trucks, and pizza, chili is one of the most beloved dishes in America. Everybody has a recipe.

According to Martina and William Neely, authors of The International Chili Society’s Official Chili Cookbook, some folks think the invention of chili goes back to the Aztecs, who sliced up invading Conquistadores, seasoned them with peppers, and feasted on them. What is known for sure is that a mixture of seasoned beans and meat was part of the diet of Aztecs, Incas, and Mayans long before Christopher Columbus arrived in the New World.

Don Juan de Oñate, the conquistador, brought green chilies with him when he entered what is now New Mexico in 1598. Native Canary Islanders, who wound up transplanted to San Antonio, Texas around 1723, were known to improvise a traditional island dish, a meat dish, with local wild onions, peppers, garlic, and other spices. Texas and cattle driving come into the story next. The drovers, as they drove their cattle from Texas to the Kansas railheads, slaughtered their cows along the way for food. As fresh beef is a bit unpalatable, the heavy spices and seasoning of chili masked the taste.

In more modern times, Macedonian immigrants to Cincinnati, Ohio transformed the dish to their liking and made that town famous for chili. In 2013 Smithsonian magazine recognized Cincinnati’s chili as one of the “20 Most Iconic Foods in America.” In my hometown of Clarksburg, West Virginia, Greek immigrants increased the levels of cumin to Middle Eastern levels and started slathering chili over hot dogs. To this day, a Clarksburg hot dog always comes with cumin overloaded chili.

The SoNo Fest can trace its beginnings back to the turn of the 21st century, when Shimazaki moved to the neighborhood. “When I moved to North Park, in 1998, it wasn’t much of a neighborhood,” he says. He didn’t have any children attending McKinley, but he knew that would be happening in a few years. “I went to McKinley’s principal and asked if it would be okay if I taught a ceramics class.” Soon afterward, Shimazaki found himself regularly going to the school and walking groups of schoolchildren down the street to his ceramic shop to teach them about clay, glazes, and firing.

Shimazaki later bought a kiln for the school, so the ceramic classes could be taught there. He then suggested a fundraiser for the school. He started by making bowls, tons of them, as he says, in his shop with the proceeds of their sales going to the school. “The first year I had $500 going to the school, the next I had $2,000, then three grand, then four grand.”

Shimazaki had also started to host neighborhood chili get-togethers. Another neighbor, Brooke Evan had a jewelry event fundraiser. They thought that it would be a good thing to combine the two events. The next thing, SoNo Fest was born. “The energy of this event is phenomenal,” says Shimazaki. “We also have a great beer selection, the finest musicians perform for the event, and you get to keep the beautiful bowls!”