Yesterday And Today

The Long, Lonesome Highway of Hank Williams

The legendary Hank Williams

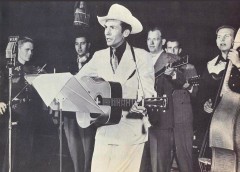

Williams and the Drifting Cowboys

It’s remarkable to consider how much esteem, respect, and awe is given to Hank Williams these days. To be sure, he is revered like few other musical icons, especially in country music. But, over the last 25 years, as the genre boundaries have blurred, narrowed, and redefined themselves, Hank Williams’ song references and tributes continue to find their way onto the music scene. Country star Jason Aldean on the title song from his multiplatinum selling album, My Kind of Party, muses, “You can find me, in the back of a jacked up tailgate, chillin’ with some Skynard and some old Hank.” While the reference is nice, the tragic side of this lyric lies in the fact that Hank didn’t live long enough to be called “old Hank.”

With all of the reverence, it’s easy to forget that Hank Williams was a real flesh and blood human being. When viewed in this light, what he accomplished in such a short span of history is all the more remarkable.

Born Hiram King Williams in 1923 in Mt. Olive, Alabama, he was keenly aware of the music of his times. The two indisputable facts of Hank Williams’ life was his love for music and alcohol. Both may have been due to the fact that he was born with a back condition, spina bifida occulta, a disorder of the spinal column. Biographers agree, the resulting pain caused him to move toward music as a career since he was physically unable to labor in the Alabama lumber industry where jobs were plentiful for young men during the ’30s. But, with the chronic pain, it was his addiction to alcohol and eventually tranquilizers and pain killers that would shape his final destiny. He began drinking at age 11 and took his last drink at 29 years of age.

Hank Williams would first hit the charts with “Move It on Over” in 1947. He was 24 years old. He would chart 34 songs in the top 40 national country charts with two songs(“Lovesick Blues” and “Jambalaya”) crossing over to the pop charts. In 1951,”Cold, Cold Heart,” by Tony Bennett became among the first country songs to go number one on the national pop charts.

He championed a public persona of a good old boy. However, most of those who knew him would have described him as a loner, painfully shy during his childhood. Thanks to early training, as a performer he learned to wear his country boy mask well. It kept most people at a distance from the pain that was buried deep inside of him. Remember, the same artist who wrote the light-hearted “Long Gone Daddy” also managed to summon up the poetic solitude and isolation of “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry.”

While several biographies have been published over the years, it’s Colin Escott’s Hank Williams: A Biography that best captures the scope and essence of Hank Williams’ life. Escott traces the music that influenced him along the way. It’s revealing and may surprise those who have yet to take a full drink of his legacy.

From the beginning, Hank Williams was authentically Christian in the most fundamental sense. His mother was a devout Baptist, even playing piano in church. She kept Hank by her side. At night he slept with a Bible in bed with him. He sincerely believed the religious songs he wrote. “I Saw the Light” and “Mansion on a Hill,” were statements of his idealized faith. But, the deeper longing in his songs, the tear in his voice, was echoed from the times he sat outside of the black churches where the music would seep into his soul in a way that informed and formed him. It was a major part of what would become his legacy. However, it was most evident in his “Luke the Drifter” series of spoken-word songs where he took on the persona of a gospel fevered, moral storyteller.

If Luke the Drifter was a pious would-be saint at battle, then in the heart of Hank Williams was the sinner, the wayward soul, the painfully lost child, and the creative genius. From this struggle another important musical influence rose up from the streets of his hometown in Alabama. As legend and history tells it, he was taught by a street blues singer named Rufus Payne. His nickname was Tee Tot, an affectionate title for the musician who always carried a brew of tea and alcohol with him as he played. He taught young Hank how to play blues on guitar, how to sing and, perhaps most important, how to get past his boyhood shyness in order to perform for an audience.

For a young white musician in 1930s Alabama, well-versed in Roy Acuff and the Grand Ole Opry, the sound of natural country blues drove his music for the rest of his life and would cause him to stand out from the crowd. It eventually would turn the world of traditional country music upside down. Songs like “Move It on Over,” “My Bucket’s Got a Hole in It,” and “Honky Tonkin’” was a kind of country music few had heard in the late ’40s when he first hit the charts. Less than a decade later the same sound would be labeled rockabilly. Hank Williams was there first.

With the breakout blockbuster national hit, the 1922 show tune, “Lovesick Blues,” the pressure mounted physically, spiritually, and emotionally on him. For a man in his late 20s, there was little to prepare him for the last years of his life: the success and the failures. The only outlet he possessed was his music. So, it was there he took his troubles to that lonely place deep within, which he carried alone as his life slowly began to disintegrate.

When Hank died bad weather blanketed the Deep South like a frosty quilt. He must have thought the coming year had to be better than 1952. In some ways that year was his best ever. His records were selling well. His creative energy was a white-hot flame against the Alabama winter skies during December of that year. But, down in the core of being, something was wrong. He couldn’t find a center of contentment to match the inspired spark that carried his best-loved songs.

If, in some ways, Hank looked like an artist on the top of the world, up close the tear and the tare in his good old boy veneer was showing through. Years of alcohol abuse and chronic back pain had taken its toll, making him appear to be a much older man than his 29 years of life. He had been recently fired from the Grand Ole Opry. Unreliability and drunkenness was cited as the cause. He had gained a reputation on the road for not showing up for gigs or turning up too late and drunk to please a crowd. He was divorced from Audrey, the mother of Hank Jr., in August of that year. By October he had married a 19-year-old beauty, Billie Jean Jones. And some time in between divorce and marriage, an affair would result in the birth of Jett Williams within days after his death. His legendary band, the Drifting Cowboys, had begun backing up-and-coming country singer Ray Price. Fred Rose refused to work with him. The only live gigs he could manage were mostly with local bands in small beer joints. It had been a year of uncertainty in what should have been a time of celebration and success. Once again, like so many times before, Hank Williams was alone at his own personal crossroad.

With a heavy sense of dreariness he went out on the road again. He hired a 17-year-old family friend, Charles Carr, to drive his limo to a scheduled New Year’s Eve show in Charleston, West Virginia after weather prevented air travel. Eventually, icy roads caused the cancelation that show. As the road trip began, Hank was drinking and had a shot of morphine administered to him by the infamous Dr. P.H. Cardwell whom he consulted for the debilitating back pain. On his way to a New Year’s Day show in Canton, Ohio, before stopping at the Andrew Johnson Hotel in Knoxville, Tennessee, Hank was drinking and ingesting chloral hydrate, a tranquilizer that helped induce sleep. During his final meal, Carr noticed Williams beginning to falter. It would take two hotel porters to carry him to the backseat of the limousine that night as he coughed and hiccupped like a man barely able to hold on to his life. It was sometime after midnight, January 1, 1953, between Bristol, Virginia, and Oak Hill, West Virginia that Hank Williams passed from life’s vale of tears into that cold winter night’s last breath of darkness. Found in the backseat of the limo were scattered, empty beer cans and an ordinary drug-store-bought spiral notebook filled with unfinished songs.

Such was Hank Williams reputation as a live performer that when his death was announced at his New Year’s Day show in Canton, Ohio, the audience broke out into laughter. But, as the band began to play “I Saw the Light” the crowd slowly understood and joined in singing.

In the wake of his death, Hank Williams became immortal in the eyes of the country music establishment. Classic songs like “Kaw-liga” and “Take These Chains from My Heart” would go to number one in 1953. His memory and estate would become a point of contention for years to come. A hit biopic with George Hamilton, Your Cheatin’ Heart was released in 1965. Hank Jr. would eventually make his own way out of his father’s shadow to make his own mark in country music. After legal battles Jett Williams, Hank’s daughter out-of-wedlock, was acknowledged as the singer’s legitimate heir. Hank Williams mercifully filed court papers for verification of his parenthood in 1952 prior to her birth.

Today, Hank has been covered by more popular artists across the genres than any country-western artist in history. His name is spoken in reverent tones wherever country music is played. He is in both the Country Music and Rock & Roll Hall

of Fame.

But, what Hank didn’t know; what no one knew in 1953, was the scope and reach of his influence over the next 60 years. It is not just that his songs have been covered by so many artists from different genres, but naturally, without effort or forethought, he fused country music with the street blues and gospel music he learned as a child. Hillbilly music, gospel, and blues were not three separate forms of music to him, but one unique brand. Today we call it Americana.

If this genre blend was his foundation, then his core was that of a devoutly spiritual man who believed in the gospel of Jesus Christ as he learned through the Baptist churches where he spent his childhood. He carried deep in his bones a faith in the religion of his roots. But, like a cancer, the wrenching back pain from undiagnosed or treated spina bifida and the subsequent and inevitable addiction to alcohol were evidence of the deep pain and helpless loneliness he felt in life. However, until the last year of his life, he didn’t let the pain didn’t stop him. Rather, it drove him on. It can be heard in his classic songs, in the timbre of his voice, in the soul that is preserved for us today.

There is no way to adequately estimate a man’s worth or to measure the extent of his legacy. But, if we could, I believe we would find that Hank Williams probably has much more than treasure in heaven, much more than a mansion on a hill. Today, beyond his music, his legacy, his legend, and the haunting way he left us, he is no longer lost and adrift on the river. Hank Williams sings with the angels in heaven in devotion to his precious savior, no longer alone and forsaken.