Yesterday And Today

The American Folk Blues Festival

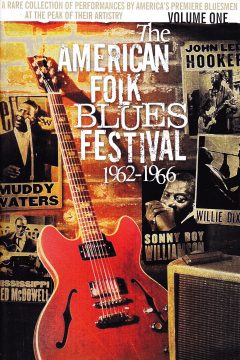

DVD cover art for American Folk Blues Festival

The author addressing The Blues Foundation.

It is February once again ladies and gents, a time when we traditionally celebrate African-American culture in this country with Black History Month. Being born and raised in the Washington, DC metropolitan area I can attest that everyday is a day to celebrate Black culture in America and yet I can easily understand how some folks might take offense at such ethnic designations and might simply prefer being called “American.” We are ALL part of a greater melting pot and I often think of myself as an all-American mongrel boy — one part this, three parts that, and a whole lot of mystery as to what it all adds up to. Humanism, perhaps. I also have a strong aversion to anyone who wraps themselves in the stars and stripes and parades about in a jingoistic fashion. However, if there is anything to be proud about regarding this diverse country of ours it is definitely the music that has spilled out from every sector of this continent over the past century (or two) and when I think of “American music” there isn’t a finer representation of it than the artists who were involved with the American Folk Blues Festival, documented on a series of DVDs and compact discs, which celebrates their tenth anniversary this summer.

The American Folk Blues Festival was a succession of annual tours throughout Europe in the 1960s, which featured the absolute cream of the blues scene in America at a time when most domestic audiences were unfamiliar with these musical giants. Over the course of several years two enterprising German promoters, Horst Lippmann and Fritz Rau, engaged the services of master songwriter and musician Willie Dixon to organize a traveling road show of the best blues artists in the world. Not that Dixon thought of it that way at the time; he was mostly lining up friends that he knew from the blues clubs around the south side of Chicago. But what a circle of friends the man had as the line up on the 1962 inaugural tour included the likes of T-Bone Walker, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, Memphis Slim, John Lee Hooker, and Dixon himself. Lippmann and Rau channeled their deep love of jazz and blues by ironically providing a forum for all of these amazing artists who were otherwise suffering a tremendous amount of hardship back at home due to apathy and overt racism. As Charlie Parker once stated, “If you don’t live it, it won’t come out your horn,” and the authenticity of these artists was a testament that each and every one of them were definitely living the blues.

I say ironic because it was only 18 years previously that Lippmann had been arrested by the Gestapo for publishing a broadsheet promoting American jazz during a time in history when the Nazi party had declared jazz and blues music to be strictly prohibited. So what a delightful turning of the tables that these two German men should be so respectful of these American artists where back home they could barely score a gig, let alone be treated like royalty and featured on national television. As with many a BBC documentary on American culture, leave it to a European to teach you how to appreciate your own history.

What I particularly love about this conceptual enterprise that we call America is the spirit and ideals that are projected through much of our musical heritage. And while we may like to cheer on the original declarations of our founding fathers, this hasn’t exactly been the land of milk and honey for many of its inhabitants. Obviously, when the slaves from other countries and all women regardless of color were deigned to have three-fifths the status of a free white male, it’s hardly what you’d call the makings of a fair and balanced society.

However, one of the unexpected side effects of all that imbalance and oppression throughout the ages is this cumulative musical form that we’ve come to call the blues — a form that we’ve been celebrating for almost a century and its influence can be found in nearly every strain of popular music since 1920, around the time that it evolved into its own genre as a derivative of jazz. A popular exercise over the years has been to define which forms of music came together to create rock ‘n’ roll, and there is an equally divergent melding of musical styles that came to be known as the blues, whether it be songs from minstrel shows, vaudeville, opera, Tin Pan Alley, field hollers, gospel, ragtime, folk ballads, or call-and-response chants — all of this and more went into the cast iron cauldron that influenced the formation of jazz (arguably America’s first true indigenous art form) and its subsequent evolution into what we now call the blues.

Significantly, it was the American Folk Blues Festival that directly inspired the British blues boom of the mid-1960s due to the fact that when the tour traveled through Britain in 1962 and ’63, in attendance were such young devotees as Brian Jones, Keith Richards, Mick Jagger, Eric Burdon, Paul Jones, Long John Baldry, Alexis Korner, Cyril Davies, and Jimmy Page. All of those musicians (and many more), spearheaded by the international success of the Beatles, took all of that American blues music, digested it through their British art college sensibilities, and brought it all back to a primarily white audience in America who were unaware that much of the music pouring out of their radios in 1964 and ’65 were largely interpretations of the type of music that was heard on these fabled tours.

Part of the arrangement that Lippmann and Rau made with Dixon for the AFBF was that in addition to the gigs scheduled throughout Britain and the European continent the troupe would also be captured on tape by Südwestfunk (SWR) in Baden-Baden, Germany for a one-hour television special. The initial response was so positive that the tour became a yearly tradition for the remainder of the decade, boasting among its lineups some of the greatest musicians of all time: Muddy Waters, Big Mama Thornton, Lonnie Johnson, Sonny Boy Williamson, Howlin’ Wolf (with Hubert Sumlin), Lightnin’ Hopkins, Skip James, Big Joe Turner, Koko Taylor, Little Walter, Hound Dog Taylor, Bukka White, Son House, Otis Spann, Buddy Guy, Otis Rush… the list goes on and on.

In a way it is a miracle that this footage even exists for us to be talking about it 50 years after the fact. By all rights it should be lost like so many other great ephemeral moments of television history. But unlike so many other broadcasts from America and abroad where the ravages of time have either destroyed these documents through sheer neglect or willful abandonment (i.e., thrown into a dumpster due to space limitations), the good people at SWR recognized the historical and cultural value of this footage and kept it properly stored for more than four decades. During my six-year stint at Reelin’ in the Years Productions where I helped to co-create the single greatest library of music performance footage under one roof with my fellow comrade David Peck, we auditioned an astonishing amount of footage from the 30-plus archives that we gained the privilege of representing for worldwide commercial distribution. SWR was sitting on a goldmine of footage and we knew it the moment that the tapes came in from overseas. Once the initial shock and awe of seeing the footage wore off it became a matter of how best to capitalize it. That’s when the real work of how to get this footage released began, with an arduous year-long process of initiating a dialog with each and every one of the artists (or their estate’s representatives) and coming to terms with a favored-nations contract that fairly compensated each one of the artists for their contribution to the project. No one gets rich on a project like this and to me that was never the goal. The true objective was to get this historic and amazing material into the hands of the general public, but to do so in a manner that was fair to the artists and licensed properly.

A key aspect in getting the AFBF out onto the market was establishing a relationship with John McDermott, a writer who had become central to the success of Experience Hendrix, the company that was created to curate the vast (and lucrative) musical catalog that was eventually awarded to Jimi Hendrix’s father, Al, after a lengthy court battle that took years to resolve. In 2001 Experience Hendrix and RITY partnered up to produce the Experience DVD (quickly earning a gold disc in the process) and other projects quickly followed. Thanks to the already established relationship that Experience Hendrix enjoyed with Universal Music, it was an easy sales pitch to convince the powers that be that the AFBF should find a home there. McDermott made some invaluable contributions from a technical standpoint by enlisting famed engineer and producer Eddie Kramer to supervise the digital transfer of the material and to clean up the audio tracks. Once the contracts were signed it became a matter of how to present the material and to make sure that all the proper clearances were in order. That took months to accomplish but when it was all over we had a product that everyone involved was thrilled with.

Coordinating the graphics for this three-volume series was another labor of love that put San Diego front and center of this history-defining project. The brick wall that was used as the backdrop for the memorable cover art was photographed by Randy Hoffman at Dick’s Last Resort in the Gaslamp Quarter with vintage guitars and amps provided by Jim Soldi of Valley Music fame. We had the good fortune to have master art director Vartan coordinate the artwork for the entire project and through a series of happenstance managed to get Bill Wyman (The Rolling Stones), Robert Plant (Led Zeppelin), and Ray Manzarek (The Doors) to contribute to the package’s liner notes. The exhaustive historical essay contained in the DVDs (and their companion audio discs) was authored by Canadian music scholar Rob Bowman.

As I wrote in the booklet’s original production notes after 20 years of archiving music performance footage and seeing thousands of hours of material spanning the last century, nothing has impressed me quite like the American Folk Blues Festival has. This material is a national treasure worthy of the Smithsonian and all that it asked for was to be presented in a respectful manner. When the project was finally released in the summer of 2003 it became an immediate worldwide sensation.

And a critical success it turned out to be as well: at the exact same moment that Martin Scorcese produced The Blues, his seven-part series honoring the idiom, the American Folk Blues Festival Volumes One and Two went on to be honored with the Keeping the Blues Alive Achievement in Film award from The Blues Foundation, a Grammy nomination for Best Long Form Music Video, and an Honorable Mention from the MOJO Magazine Music Awards. Volume Three of the series was also honored with Best Music Anthology from the DVD Entertainment Awards and won the Best Compilation Award from the Home Media Retailing Awards.

There are some seasons when everything you touch turns to gold and so it was a decade ago when I was afforded a glimpse into the inner sanctum of show business and found out what it is like to don a tuxedo and walk down the red carpet at the Grammy Awards and to step up to the podium in Memphis to accept an award from your peers in the music industry. It was a lot of work for everyone involved to experience a moment like that and I am forever grateful for the memories. But I’m mostly grateful that these legendary artists have been preserved at the peak of their artistry for the edification and enjoyment of future generations.