Yesterday And Today

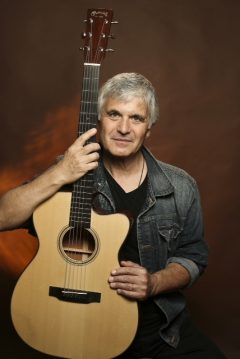

Sideman in the Spotlight: LAURENCE JUBER

Music may be many things to many people, but it is primarily an emotion delivery system. When you throw a disc upon the turntable and press “play,” what sort of experience are you expecting? Since context is crucial to understanding anything in this world, it all depends upon where you’re standing at any given moment. As wildly dynamic social animals, it’s also about creating the proper mood for the task at hand. If you’re getting primped for a night out on the town, you’re probably looking for something to get you pumped as a precursor to clubbing. If it’s a Sunday-morning-coming-down sort of scenario, you might want to explore some cool jazz or a Bach composition for cello. Or, perhaps you crave a little hair of the dog that bit you with additional doses of Rage Against the Machine or James Brown to balance out your barometer? After all, one person’s drill bit is another person’s “Ode to Joy.”

But what is it that impels you toward the work of any one particular artist? Why would you want to keep coming back to that same well of initial inspiration and attraction? Most likely, it’s because the artist in question is reflecting how you already feel. Is it possible to enjoy the music of Kurt Cobain without possessing the soul of an angry, wounded adolescent? And how mature or sophisticated do you have to be to appreciate the melodic and harmonic genius of Duke Ellington?

While virtuosos may be a dime a dozen, their technical facility is by no means a guaranteed soul-kiss to your psyche. How does one’s art affect your consciousness? Does hearing a particular piece of music raise your heartbeat? Get you excited? Mirror your melancholy? What is it that you need right now to make you feel good or serve as a balm for what is aching within?

Whether you have struck the perfect Zen balance within, or are attempting to soothe your own internal savage beast, you are directed to the fingerpicking stylings of master guitarist, arranger, and composer Laurence Juber. As a stylist, Juber is a hard nut to crack and even harder to classify for demographic purposes. With 24 compact discs to his credit, and a CV that includes workmanlike anonymity as a professional studio musician, until Paul McCartney tapped him to become lead guitarist for the final version of Wings in 1978. Juber possesses the versatility of several guitarists all rolled into one, which is rather apt, because when Juber performs solo he creates the illusion of two (or more) guitarists dancing in tandem. It’s a rather remarkable achievement, considering he possesses no more than eight fingers and two thumbs.

“That’s the concept,” says Juber. “To be self-sufficient. And that goes back to opening up for people like Martin Carthy when I was 14 in folk clubs in London–seeing that kind of self-sufficiency of the single musician: with a guitar, no PA, and just commanding the room became part of my solo ambition.”

*********

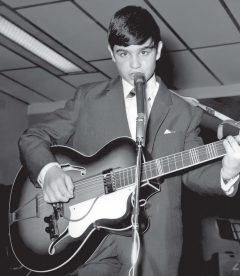

Juber was born on November 12, 1952 in Stepney, a district in the East End of London, England, and it was on his eleventh birthday that his parents gifted him his first guitar.

“I fell in love with the instrument from the moment I started playing it,” he says, “and I just never put it down. And after I very quickly realized that I could make money doing it–the choice was between babysitting, washing the neighbor’s car, or working at the supermarket on Saturdays–the idea of making money playing guitar beat all of the others.”

So, a bit of the magical and mystical mixed in with the pragmatic?

“Oh, yeah!” he says laughing. “Because I decided that’s what I wanted to do for a living, to become a professional guitar player. It just felt right to me.

“And I learned how to sight read very early on. There was a book that a lot of English guitar players used called Play in a Day, written by a man named Bert Weedon. That was one that was commonly used for players to get started. In the back of the book it had the music for “When the Saints Go Marching In,” just the melody, in C major. And I looked at the music on the page and figured out where it was on the guitar, and one rainy afternoon I learned how to sight read.”

The Grammy-winning guitarist makes it sound so easy. “Of course, it takes a lot of practice to get it down, and the fact is that over the years I discovered that a lot of what it meant to be a studio musician didn’t necessarily mean reading notes or reading chord charts or coming up with stuff: I lived in a more educated space. Because I didn’t just study theory at London University, I studied musicology, the history of music and musical style, which was a very valuable thing, because it taught me how to analyze music and figure out how it worked. Not just from the harmonic or the melodic rhythmic point of view, but also in terms of its stylistic context, which is a very valuable skill set for being a studio musician.”

By the time Juber was 15 he was performing with the National Youth Jazz Orchestra, eventually earning a music degree at London University’s Goldsmith’s College. As a session guitarist, one of his first projects was working with producer George Martin on an album for Cleo Laine (This Is Cleo Laine). Later session work had him working with Charles Aznavour, the Alan Parsons Project (Tales of Mystery and Imagination–Edgar Allan Poe) as well as on the soundtrack to the 1977 film The Spy Who Loved Me (and for all you trainspotters out there, the “James Bond Theme” was written by fellow Stepneyite Monty Norman).

But it was during a stint working on the BBC television program David Essex, that he encountered ex-Moody Blues guitarist and vocalist Denny Laine, now of Paul McCartney’s Wings. Six months later he was invited to play with Laine and the McCartneys, and after spending a day jamming on Chuck Berry tunes and a few reggae numbers, Juber was asked “what are you doing for the next year?” After being well hidden in obscurity, suddenly Juber was thrust very publicly upon the world stage, and at the tender age of 25 found himself in a band with an ex-Beatle.

“Yeah, it was a big shift. Because I went from being behind a music stand to being on stage with Paul McCartney. Professionally, it was certainly a step up. I didn’t seek the spotlight. I was a shy teenager. Being a studio musician was a cool thing for me to do, because I didn’t have to worry about getting up in front of audiences. Not that I didn’t do it–playing with Top 40 bands and my own projects–but it wasn’t the focus of my attention. I just wanted to be the best guitar player I could be. Joining Wings kind of thrust me into that very different mode of being a musician. It was a great education: I think of it as getting my masters from McCartney University.”

The immediate fruits of that “masters program” were evident when Juber began working on the final Wings LP Back to the Egg, along with the stand-alone hit single “Goodnight Tonight” b/w “Daytime Nightime Suffering.”

“We were encouraged to think of ourselves as a band,” he says. “We started up in Scotland on Paul’s farm, in this kind of rustic environment, and it did feel very much like a band project. We were all living together, essentially set up with bedrooms above the top floor of the barn, and we were recording every day. It was very liberating for me, because I was used to three, four sessions a day: 8am jingle, 10 o’clock record date, 2 o’clock record date, 7 o’clock pre-record at the BBC for a variety show–very scheduled. And all of a sudden I’m in the studio in Scotland where we’re working on a tune a day, instead of three tunes in a three-hour session. So it was a lot more relaxed, but of course it was a lot more responsibility because you really have to deliver the right kind of musical attitude, too. It was a great difference to what I had previously been doing.”

After finishing up the LP, Wings conducted a short tour of the U.K. before arriving in Japan on January 16, 1980, for an ill-fated, 11-city tour that was immediately cancelled when Japanese customs found 219 grams of marijuana in Paul McCartney’s suitcase. While no official charges were pressed, McCartney ended up being detained for a total of ten days before being released in what must have been a nerve-wracking experience.

“Yeah, we didn’t wait out ten days–they actually had us leave after about three days. And I was standing right next to him when he got busted!” Was there any fear of guilt by association? “No. Everybody had vacuumed their pockets. It was not so much reprisals, they just thought it would be better if the band wasn’t going to be hanging around there, because the tour wasn’t going to happen at that point. It got cancelled immediately.”

*********

Wings soldiered on until April of 1981, and after the Japanese debacle, Juber was invited to France to work alongside McCartney on Ringo Starr’s Stop and Smell the Roses LP. In addition to the three tracks that McCartney produced for Starr’s LP, Juber played on Linda McCartney’s “Love’s Full Glory” (released on the posthumous collection Wide Prairie). Juber also recorded with George Harrison on the Shanghai Surprise soundtrack, giving him the rare distinction of appearing on three different ex-Beatles records. “Three out of four’s not bad!” he says with justifiable pride. There is a charming anecdote on Juber’s official website written by his wife, Hope, titled “Meeting George Harrison” that relates how Hope went into labor with their first daughter Ilsey as Laurence was in the studio with Harrison.

“That is a great story, and our daughter Ilsey is, in fact, now a successful commercial songwriter [Shawn Mendes, Pitbull, Beyoncé, Train]. So, when George blessed her and gave her the gift of music, it really took. In fact, she’s much more active in the music business than I am now: I pretty much just do my own projects.” It is quite the show biz family; with Juber’s wife being the daughter of the late television producer Sherwood Schwartz (creator of Gilligan’s Island and The Brady Bunch). And they have another daughter as well, Nico.

After a few years in Wings, Juber moved to New York, where he met his future wife, and eventually transplanted to Hope’s native Los Angeles. His subsequent list of credits as a studio musician is name-droppingly impressive: four LPs as Al Stewart’s producer; recording with Eric Carmen on “Make Me Lose Control”; Belinda Carlisle’s “Mad About You”; the Dirty Dancing soundtrack. And that doesn’t include working on a variety of American television programs. He laughs at the mention of Happy Days and Laverne and Shirley. “I played on the last season of Happy Days, but that would have been just background music. I don’t think I played on either of those main themes. I did play on the theme of Home Improvement; the first six seasons of Roseanne, a lot of stuff like that. It’s all local 47 union gigs.

“You know, it’s a professional job: it’s being a studio musician. You walk in, they put music in front of you, and you record maybe ten second cues. Sometimes you get to do a theme song; sometimes you get to do a production number. Sometimes they even call you in to be on camera. What counterbalances that is the record sessions where you might be doing something really cool. It’s all in a day’s work.”

In addition to his own solo catalog, Juber has a series of instruction books and DVD guitar tutorials. He says his approach is different from the Bert Weedon/Hal Leonard/Mel Bay method of instruction. “Very little of my educational stuff is built on the basis of rudiments. Much of it is just me explaining how I do certain things rather than guiding a player from first steps to more evolved steps. The one exception to that is a rhythm guitar course I did for the company True Fire, which is a much more basic thing. I also have a DADGAD tuning tutorial that’s available on DVD or online, which breaks that concept down to a more rudimentary level.”

Juber’s most recent LP, Holidays and Hollynights (reviewed in the December issue of the Troubadour) is one of the rare instances that he has recorded with a rhythm section, deviating from his predominant cannon of solo fingerstyle guitar work. His next CD, due in the new year, is a return to that format with his third volume of Beatles arrangements, titled LJ Can’t Stop Playing the Beatles. It arrives just in time for Juber to perform in March at Beatlefair in New Jersey with ex-Wings Denny Laine and drummer Steve Holly. “I always enjoy playing for a Beatles audience, because they have a very dedicated perspective on all of that.”

*********

Having worked with some of the greats in pop music history, I wonder if he thinks of himself as primarily a sideman, an artist, or an entertainer?

“I guess the question is: how do you define artistry? And I would define being an entertainer as part of the artistry. Certainly in George’s case there was a philosophical underpinning to it. In Paul’s case, I think it’s just pure musicality and it’s pure entertainment–he’s just trying to engage and entertain his audience. I think there was a certain tortured-soul aspect to John that tends to color his own opinions of his work. But with him there was a slightly avant-garde aspect–pushing the envelope, where you get “Strawberry Fields Forever” or “I Am the Walrus.” Songs where he’s really breaking the conventional pop-song mold. I don’t think Paul ever tried to break the mold as much as just expand the existing parameters of it. I think Paul works very much from within a conventional, harmonic/ melodic context that just has it’s own twist to it. John didn’t always work conventionally. And George was really a pioneer of the world music concept, like “Within You, Without You,” which is clearly raga inspired. But even on “Here Comes the Sun,” the bridge section of that is actually based on an Indian rhythm, so he was incorporating those kind of elements, even when it’s not obvious that is what he was doing.

“But Paul just has a tremendous, natural gift for melody. And having a very broad understanding of musical style–this goes back to the earlier part of our conversation it terms of understanding style and context. Paul can apply himself to something like say “Honey Pie,” which has a very kind of ’20s feel to it, applying himself to that and creating something that feels very much of that era, and yet still has a modern sensibility to it. I mean, think about the fact that he wrote “When I’m Sixty-Four” when he was 16 years old. That was always kind of ‘in there,’ that ability to encompass a range of style. Part of the reason I got asked to join Wings was because I was a versatile musician. I could play many different styles and that was something that Paul needed.

“And yes, something like “Honey Pie” is pastiche, but it’s cool, it’s fun, and it has some interesting musical twists that lends itself to being a vehicle for some kind of expression. Whether that’s purely the entertainment value of it or whether there’s room for something improvisational. The thing that I’m always trying to do is take the familiar and make it transformative, so that you’re hearing it in a different perspective, because it’s being done as a solo guitar piece.

“And being able to do that kind of transformative thing, but there’s also the entertainment aspect. When I do a live show, the goal is to entertain and engage the audience: to offer them a range of material. When I do my shows it’s typically a mixed bag of styles. I can segue from something jazzy to something rock to something folky, to something original, a Beatles song, a Who song, Hendrix, something from the Great American Songbook–it all seems to hang together because I have a consistent approach to what I do. I have never really sat neatly in the New Age category in the way that there are certain guitar players–like the whole Windham Hill school in the ’80s, Windham kind of defined that. I never quite fit into that textural thing. The rock aspect, the jazz aspect–those aspects tend to infuse what I do.

“What I do is not ambient music, although some of it may get used that way; what I do is I try and make it a unique, artistic statement by virtue of channeling the essence of the material into a guitaristic concept that is typically self-sustaining. The fact that it is incorporating the bass line, the melody, the rhythmic aspects of it, the little orchestral bits on the Beatles songs for example–all of that. It’s how it all fits together.

“And it’s fun to talk to the audience. I’ll tell stories: sometimes I might bring back stories that I might have told a decade ago–but a good story is a good story. It varies from night to night. I like to look for those sorts of spontaneous moments–hoping for some kind of transcendence to really kind of kick it up to another level.”

Don’t miss Laurence Juber at Grassroots Oasis on Saturday, January 7, 8pm. For tickets and info: GrassrootsOasis.com