Yesterday And Today

San Diego Roots Led to DANIEL JACKSON’s Journey into Jazz

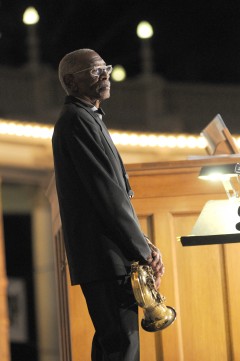

SDMA Lifetime Achievement winner Daniel Jackson. Photo by Thomas Westerlin

Sitting on a bench outside the San Diego Automotive Museum on a beautiful late-August midday morning, Daniel Jackson looked around and said that there was a time he knew the location of every piano in Balboa Park.

“I had the keys to every building — and I found the best piano to play!”

After having toured with Ray Charles in the late ’60s, Jackson spent the late ’70s teaching jazz at the Universidad Veracruzana in Veracruz, Mexico. When that job came to an end, he moved back home to his native San Diego.

“I thought, ‘Well, I better find a job,’” Jackson remembered. After being hired by the city’s Department of Parks and Recreation, he was assigned to Balboa Park and volunteered for the unpopular weekend shifts.

His free use of the city’s 88s didn’t last long, though. After just a few months on the job, news of his unauthorized practice sessions filtered upward.

“One day, one of the other guys says, ‘The head of the department wants to talk to you.’

“I go in, and he says, ‘Mr. Jackson, why don’t you go be a musician. I can never find you when I need you, and I know where you are.’”

Jackson swept his arm across the view of the international cottages, organ pavilion and Hall of Champions.

“My last ‘other job’ was right here!” he laughed.

His main job — that of jazz saxophonist and pianist — has turned out all right, too. In August, the L.A.-based Living Legend Foundation honored him alongside Les McCann and Bobby “Hurricane” Spencer. And on October 9, he will receive the San Diego Music Awards 2013 Lifetime Achievement Award.

*********************

“I grew up here in San Diego. I graduated from San Diego High School.

“My mom took care of three kids by herself; it wasn’t easy in those days — particularly for an African-American.

“My parents were living in La Jolla in the Quarters, where the black domestics lived. My dad was a chauffeur for a white doctor. When my dad got cancer, his employer wouldn’t help him.

“At nine months, I got sick and my mom went back to Scripps Clinic, where I was born. They told her to take her baby home to die. She’d already had a miscarriage and her husband was dying. She took me home and laid me down and went out in the alley to cry. An older woman, a black woman dressed all in black, came walking down the alley and asked my mother why she was crying. My mother said, ‘My son is in the house and he is going to die.’ The woman said to ‘bring him outside’ so she could see me. The woman told my mother to go to the meat counter the next day and to get hog hooves and make a tea and I would live.”

“The next day my mother asked around about who this woman was, but nobody had ever heard of her and my mother never saw her again. That was 76 years ago.

“Well, when I was about six years old, my father died and my mom doesn’t know what to do. She’s never had a job. She called her father, a minister, and he said to put the kids in church every week. And that’s what she did.”

Despite the challenges of raising three kids on a working-class income (and purchasing the house in Southeast San Diego that Jackson still lives in), Jackson’s mom managed to afford saxophone lessons for him in addition to keeping him active in Boy Scouts.

But music was his passion. That it was a tenor saxophone he wanted to learn was due to the fact (as related in an interview with KPBS in January) that his older brother, Fred, played piano in trumpeter Fro Brigham’s band in the 1940s. Jackson told KPBS (tinyurl.com/azashuq) that it was hearing Harold Land play tenor sax while practicing with Brigham’s combo in the family’s living room that led him to the horn.

*********************

A desire to help his mother ended up taking Jackson on a twisting road to a life in jazz, leading him to his first contacts with professional musicians — and opening a series of doors that led to his career.After graduating from high school, Jackson said he thought, “I think I’ll go into the Air Force and save some money and buy my mom a bigger house.“So I went down to the recruiter and said I want to join the Air Force, and the recruiter said, ‘Okay, just sign here. Where would you like to serve?’ And I said I’d like to go to Japan. So they sent me to Illinois in January — freezing, with snow and ice!“But I was fortunate. I was sent to Rantoul, Illinois Chanute Air Force Base near Champaign. The University of Illinois is there.“When I was off-duty, I would go to the black part of town, to the VFW hall.”And he took his saxophone with him (he was assigned to an Air Force band at Chanute).

At that hall, he met, listened to, and was able to play in impromptu jam sessions with organist Jack McDuff (who lived in Champaign) and guitarist Wes Montgomery, who was based out of nearby Indianapolis.“I went to play with them for three years. I wouldn’t have found them if I was in Japan.”Those who marvel today that Jackson is equally versatile on both tenor saxophone and piano may find examples of multi-instrument virtuosity early in his career.In the KPBS interview, Jackson related seeing Ray Charles play saxophone for his band — and did so brilliantly.Even before witnessing that, though, Jackson said he saw McDuff give the bassist a lesson on his own instrument.“One time in that band, Jack McDuff got off the organ, went over to the bass player, took the bass out of his hands and said, ‘Let’s get that tempo back where it belongs.’”

*********************

During his military service Jackson was making new professional and artistic connections beyond Champaign.“When I was in the Air Force and had leave, I would stop in L.A. at jam sessions on my way back home. I met Teddy Edwards, a tenor player. I was just a kid — 21 or so.”

Edwards apparently remembered Jackson and was apparently impressed with what he heard.

“After I got out of the Air Force, I came back to San Diego. I got a job as a janitor at the Sears warehouse, but practiced my horn every day.

“One day a phone call came from someone I don’t know: ‘Do you want to join this band?’”

It was East Coast drummer Lenny McBrowne, who was starting his own band out of L.A. after stints with Sonny Rollins and Harold Land.

“This band was my first professional job. Our first gig was in Denver in 1960; we were a quartet. Lenny asked if I knew a trumpet player, and I said, ‘Yes, but he’s white.’”

“Lenny said, ‘I don’t care if he’s a polka dot, can he play?’ I said ‘Yes!’”

The trumpet player was fellow San Diegan Donald Sleet.

“The only reason I knew him was [because] I crossed the color line! I played with Don and Gary Lefebvre and Bob Magnusson.

“I was in New York once, and one of the guys there said not to play with the whites, and I asked why, and he said, ‘Well, they’ll learn this music and start their own bands and they won’t hire you!’”

The same year that Jackson joined McBrowne’s band, they had a recording date in New York City.

“We went into the studio in New York; Cannonball had sponsored us. The engineers at Riverside Records walked out of the booth and gave Don Sleet a contract on the spot. That’s how good he was.”

(Those sessions are currently available as Lenny McBrowne and the 4 Souls: Complete Recordings.)

That first job also taught Jackson another important lesson: Don’t underestimate the drummer, particularly if he is the leader.

“Lenny was a Juilliard grad and had studied with Max Roach,” Jackson remembered.

“Don Sleet and I did some alternate chord changes one night, because we thought Lenny was just a drummer. He comes up to us after the show and says, ‘You guys played some pretty wild stuff up there.’ We’re just like, ‘Oh, thanks.’ He looks at us and says, ‘Don’t ever do that shit again.’

“He was like somebody I never knew before.”

*********************

If his initial sound on tenor sax was shaped by his lessons as a youth in San Diego and his stint in the Air Force, Jackson’s piano playing is self-taught.

“I had a saxophone teacher — not jazz, but saxophone. Never had a piano teacher.

“I had a classmate named Peggy Menefee who wanted to be a singer, and I’d been messing around on piano, teaching myself chords. Pretty soon, I was playing for her.”

If self-taught, it’s not that Jackson was without influences — his grandfather’s direction to Jackson’s mother that she take the children to church ended up shaping his piano playing.

“Every Sunday, Essie Smart came to our church (and every other church in the community) and played piano. She was imprinting on me, even though I didn’t know it because I was only seven or eight. When I got older and started playing, I could feel the music from listening to Essie for years.

“I ran into her 42 years later at another church. We were playing at this church, and the band was set up in front of the piano. While we were warming up, I hear a chord played on the piano behind me — and it sounded like MY hand played it. I turned around, and it was her: Essie Smart.”

*********************

Receiving the Living Legend and Lifetime Achievement awards shouldn’t make anyone think Jackson plans to slow down anytime soon. He said the Barbara Dennerlein concert where he was guest artist at the Spreckels Organ Pavilion in Balboa Park on July 29 “was my finest and favorite concert ever. Barbara is a fabulous musician — it was an honor and privilege to be there with her.”

And besides, it’s not like he’s anywhere near the oldest player in his own circle of musicians.

“This last Sunday, I played a gig with Hollis Hassel, a drummer who played with Fro. I said to him, ‘Man, tell me something — just how old are you?’

“‘91, he said.”

†††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††â€

The San Diego Music Awards is an all-encompassing event, taking in every genre. But looking at past winners of the Lifetime Achievement Awards, the local jazz luminaries previously honored show Jackson to be in pretty rarified company:

Mike Wofford

Mundell Lowe

Jeannie and Jimmy Cheatham

Charles McPherson

Joe Marillo

Barney Kessel

Considering that the recently departed Gary Lefebvre and the late Hollis Gentry III, Carl Evans Jr., and Chubby Jackson were never recognized with a Lifetime Achievement Award; that Fro Brigham, Jimmy Noone Jr., Dinky Morris, and Ella Ruth Piggee all passed long before the awards came into being; and local jazz luminaries Peter Sprague, Bob Magnusson, Fred Benedetti, and Bert Turetzky (among many others) have yet to be honored — well, surely Jackson is in a pretty elite fold.

All of the previous jazz honorees except Marillo have or had national reputations, playing the top clubs and biggest festivals across the country.

Jackson’s value to San Diego’s music community (as with Marillo’s) lies in all the local gigs he’s played around town over the past half-century, and the tens of thousands of fans whose lives have been enriched through sharing in his music.

Two of the most memorable times I’ve heard Jackson play were in the past 20 years. I saw him in the late 1990s playing in the old nightclub atop the hotel on Sixth and Spruce (before it was remodeled and renamed). Jackson was on the piano that night, with Chuck McPherson on drums. During the last set, a small group of 20-somethings came in and set up a couple of congas and began playing with the band. Then a young woman with a startling resemblance to Chaka Khan came out and began to dance to the music up on the bandstand. Utterly remarkable.

In the summer of 2005, local jazz vocalist and longtime KSDS dee-jay Peggy Claire was passing from cancer. At Buddy Blue’s suggestion, I had interviewed her for the North County Times and Turbula.net, and we’d struck up a friendship over our shared love of Bing Crosby’s music and Ernest Hemingway’s writing. She didn’t have much time left — and knew it — but she wanted to go see and hear her good friend Daniel Jackson, who was playing the soon-to-close Prince of Wales Room at the Hotel Del.

We went on a weeknight, and the place was empty. Just Daniel on the piano, and Peggy and I listening. Daniel came over and told Peggy how lovely she looked, insisting she come sing a couple songs with him. Never has a music fan been so spoiled as that audience of one was that night, as two old friends played together one last time.

— Jim Trageser