Yesterday And Today

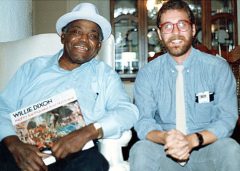

Remembering Willie Dixon: July 1, 1915—January 29, 1992

It doesn’t seem possible that it’s been 25 years since the passing of bluesman Willie Dixon. Willie lived life exactly like he wrote songs–simply, without pretense and gut level. A huge presence in both girth and talent, Dixon became a voice for the mistreated and broken-hearted. He was gifted in musical arrangement and composition; even today he is considered to be one of blues music’s most prolific songwriters. Purists need look no further than the Chess or Cobra libraries to appreciate Dixon’s intuitive skills in pairing songs with musicians and players with sessions, then successfully recording the best from both.

As a studio producer, songwriter, session player, and stage performer, Dixon had few peers. His remarkable body of work has long been considered the genre’s gold standard. A keen ear for talent and ribald sense of humor made him versatile, but Willie’s observations of the human condition and flair for innuendo made him legendary.

Relating life’s experience through music became Dixon’s 12-bar documentary of the world around him. “That’s why I wrote so many songs,” he said. “Because I’ve been writing about the true facts of life that exist today and what I hope tomorrow will be a better future. I’ve been writing songs all my life, you know? I used to walk around with a gunny sack full of songs. I used to sell them outright for $10!”

Born seventh of 14 children, Dixon began his pursuit of the blues at the tender age of eight. “I was a kid in Mississippi,” Willie said. “And we used to be outside of a place called Zack Lewis’. He had a little tavern; they called it a barrelhouse in those days, and Little Brother Montgomery would be in there playing piano with his band. We used to follow Little Brother all over town. I’d be bare-footed, running up and down the road behind them, they’d be up on a wagon bed or a T-model Ford truck and he had a piano up there. Little Brother was short and little at that time and we always thought he was a kid, but he was several years older than we was. I know every time we chased him all day long, I’d go back home and get a whippin’ for missing school and following the band all day.”

Those first short, dusty steps started Willie down a path he embraced with open arms and, occasionally, clinched fists. Brushes with the law and time spent in reform school exposed the young Dixon to the serrated edge of life. “I used to be a fighter, you know? I used to train at Eddie Nichol’s Gym in Chicago. Fightin’ is a hard job. I won the Golden Gloves in 1937 and I fought pro a few times. Fights get into your system like everything else until you finally get beat enough to give up. I got a chance to train with the ‘Brown Bomber’ [Joe Louis] down at Nichol’s gym and I was supposed to go on a tour with them, but I never did. My manager didn’t want me to get ‘shell-shocked’ before I got out there too far, you know?”

Shell-shocked being the pivotal word here… wise beyond his years, Willie contemplated his options. “After sparring with Louis,” he began to grin. “I knew from that point on, and for the rest of my life, that I wanted to be… a songwriter! The music don’t fight back and you don’t have to be ducking and dodging and running and keeping yourself together, you know?”

Chicago, in the late ’40s, was Mecca for blues players, and musical styles reflected that diversity. Experimentation and amplification were transforming the Windy City. On any given night Willie told me you could find Big Maceo, Memphis Slim, Sleepy John Estes, Sonny Boy Williamson, Memphis Minnie, or Son House hanging out at Tampa Red’s place.

“Tampa Red had a big old room back there,” Willie remembered. “He lived right up over a pawn shop on 35th and he had an old, raggedy bed sitting in the corner and a broke-down piano in another corner. Everybody could get in there and could sit on the bed or on the floor or on the piano and they’d all be in there arguing about songs, you know, and making songs, like that. Lester Melrose would be in the front room and he’d always have the old lady cooking something–chitlins or something. He’d come back there, ‘What you fella’s got?’ And each one would come up with what he got.”

Creative juices flowed like hot grease down the Melrose stove. Willie continued to work gigs with Leonard Caston and Ollie Crawford and it was that trio that first appeared on stage with yet another transplanted Delta bluesman. Those early appearances would begin a personal relationship that forever changed the world’s perception of the blues.

“Muddy Waters was one of the first ones that starting doing some of my tunes, you know? I was walking around with 200 songs in a bag and nobody would do none of ’em! I’d go around and sing ’em to him, so he said, ‘Man, I like that song.’ I had a little trio called the Big Three Trio at that time; we had recorded for Columbia and also for Bullet Company. We done that song about the ‘Signifyin’ Monkey’ and ‘Wee, Wee Baby You Sure Look Good to Me’ and other songs… So this ‘Hoochie Coochie Man,’ Muddy Waters liked it, you know? So I started to go out there and jam with him, with our trio. He told me, ‘Man I sure like that song; if you let me, I’ll record it.’ Sure enough I got with Muddy over on 14th Street one night, I took the song over there and he said, ‘Dixon, I’m gonna’ do that song tonight.’ He didn’t know the song; he’d just heard me singing it. So I took him in the washroom on the intermission, and we practiced the song. He walked out of there and he said, ‘Man, you better let me do it first, so I won’t forget it. By the time he came out of the washroom, he went on the stage and he started doin’ the ‘Hoochie Coochie Man’ and he done it ’til the day he died.”

Writing music occasionally created conflicts among Willie’s friends, especially if an artist wanted, or didn’t want, to record a certain song. Dixon was the first to admit that writing the song wasn’t necessarily the most difficult part of the recording process. “Sometime I just have the idea of the experience that people go through, involving themselves in different things, and this is what I write about. And then sometime I try to find people that I feel like can properly express these things, because sometime people can express a thing better than another one… sometime.”

One case in point is “Wang Dang Doodle”: “Oh yeah, Howlin’ Wolf recorded it long before Koko Taylor, but the Chess Brothers wouldn’t release it. In fact, I wrote a lot of things for people they never actually would accept and I’d have to give it to somebody else. And then ten to one after somebody else got it, then they’d like it. I used to always have trouble with Muddy and Wolf because one thought I was giving the other one the better song, you know? So I got to the place [where] I just used a little backwards psychology on ’em. The one I be writing for Wolf, I tell Wolf, now here’s something I wrote for Muddy and that’s all I need to do. Wolf would say, ‘Man, how come you got to give that to him, that’s better than mine.’ And vice a versa, that’s the way it worked.”

Another case in point, “My Babe”: “I had a hard time in getting Little Walter to do ‘My Babe.’ Two years I was trying to get him to do ‘My Babe.’ He didn’t want to record it. He just didn’t like it. But after he recorded it and it started going over, it was his top running number.”

A MAN WITH A MISSION

Willie considered retirement when he moved to Southern California, but it wasn’t to be. “Ever since I’ve been out here,” he said. “It’s been one thing right after another. I try to back off from ’em, but with the Blues Heaven Foundation I have retired away from working for myself, and by being able to reap some of the benefits of some of my own royalties that I should have got years ago. And this is why I started the Blues Heaven Foundation so I could help other people not as lucky as me.

“Not only does it try to get some of the capital that’s been owed to artists, people who been beat and cheated out of their thing, but we also help ’em to learn how to protect their songs and copyrights. We do this with donated capital and the Blues Heaven Foundation takes not a penny from nobody. All the people that has passed on and their families didn’t get anything, all they had to do is prove that they are involved or in the family and they can reap the benefits of their forbearers.

“You know when you feel like you’re underprivileged and know you’re underprivileged and not getting your rights; you always want to know why. Believe it or not, [prior to the civil rights movements in the ’50s and ’60s] people didn’t know they had a black law book and a white law book at that time, but today most of them know about it. It wasn’t until after the Martin Luther King-era and the government ratified the 14th and 15th Amendment, that everybody had to hear us out and give us just dues just like everybody else.”

BLUES HEAVEN

“That’s the reason I’m trying to expose the Blues Heaven Foundation, because you don’t have to die to enjoy the great things of life. You don’t have to get to the place where you have to have this religion or that religion, fighting over ten dollars and then tell me you’re going to a place where the streets are paved in gold. Don’t you know I don’t want to go there if you’ve been raising as much hell over a dollar here? So I figure if we can enjoy the luxuries of life here as we should, everything is here you need. They say if you went to heaven you’d get milk and honey. We got milk and honey here!

“It’s just a matter of time because you see, everything changes. People get more experience and understand each other better, but when you haven’t been taught any of the right things, naturally you can go wrong because you’re only thinking about yourself and not others.”

With a chance to reflect on his life and given the option to change the outcome, Willie just smiled. “Frankly, with the experiences I’ve had since I’ve been involved in these blues… I wouldn’t take billions for it, but I wouldn’t want to do it all over again for trillions’.”

Through his Blues Heaven Foundation, Willie continues to touch the lives of disadvantaged youth and the surviving family members of early blues greats. Whether it’s assisting students through scholarship programs, donating musical instruments, or recouping lost royalties, Blues Heaven continues to educate, perpetuate, and carry out Willie’s most heart-felt wishes.

Willie Dixon lived, worked, and breathed the blues. His music conveyed the depth and drive of that battered old upright bass. To use boxing vernacular, it was his combinations. He could double you over with thumping bass lines and drop you to your knees with devastating lyrics. The name Willie Dixon will always be synonymous with the blues, but to paraphrase the late Dr. King, it’s the ‘content of his character’ that we’ll all miss the most.