Yesterday And Today

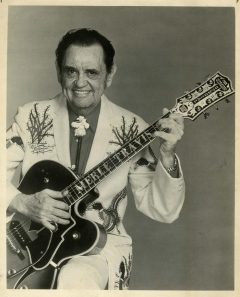

Memories of Merle

Lou Curtiss interviews Merle Travis, Part 2

There was that fateful day at a certain Tex Ritter recording session when Merle Travis and Cliffie Stone (real name Clifford Snyder) met. Merle was waiting his probation time (three months) while he transferred his membership in the American Federation of Musicians from Local 1 in Cincinnati to Local 47 in Los Angeles.

Merle Travis: Tex Ritter gave me $100 to see me through these hard times and I promised him I’d give him some gig time in the studio or on the road or wherever. During that time I was workin’ in the honky tonks, mostly with Charlie and Margie Linville, and sometimes with Texas Jim Lewis and his brother Jack Rivers. The first thing I did when the probation ended was a dance date with the “Pistol Packin’ Mama” man Al Dexter and did some radio stuff with Tuttle [Wesley Tuttle]. On September 20, 1944, I did that first Capitol session to pay back Tex, and that’s where I met Cliffie. He was calling himself Cliffie Stonehead in those days and he was all over the Los Angeles radio scene as an MC, comedian, and long-time studio bassist. He and his dad, a long-haired, bearded comic who called himself “Herman the Hermit,” had joined the Stuart Hamblen radio show group in the early to mid-1930s. By the time I met Cliffie he had his own show with a gal named Dixie Darling, and he invited me on that show along with a fellow Kentuckian named Tex Atchison who could play one heck of a fiddle. Tex had been with the old Prairie Ramblers for most of the 1930s, and when I met him he’d just left the Riders of the Purple Sage. Tex was from Bill Monroe country—Rosine down in Ohio County—and he learned his jazz swing stuff and Smith-Clayton Macmichen style of fiddle from Arnold Schultz, the same guy who influenced Bill. That long-bow fiddlin’ stuff. I think Tex was one of the best musicians I ever worked with. He played on nearly all my Capitol recordings in the 1940s, and I did a lot of club and barn dance and radio work with him too.

What other bands were you working and recording with in those early years in LA?

MT: Well, about the same time, as I was playin’ on Cliffie’s radio show, ol’ Smiley Burnette introduced me to Ray Whitley [the guy who wrote “Back in the Saddle Again” and lots of other songs for Gene Autry] and I became a part of his Rhythm Wranglers. At that time they were one of the top western swing groups on the L.A. ballroom circuit. There were lots of good folks in that band. While I was with them Joaquin Murphy, Herb Remington [pre Bob Wills], and Noel Boggs all played steel; fiddlers included Tex Atchison and Jesse Ashlock, and a co-lead guitar man by the name of Charlie Morgan. [I might mention here that I heard from Cliffie Stone that the bass player in that group was Sydna “Tex Ann” Nation, who later married and recorded with Merle. Merle was always reluctant to talk about the more personal side of his life with a young squirt like me. Cliffie and Hank Penny told me an awful lot and while I don’t want to dwell on it, I’ll include factoids where relevant.] The hours this band worked were incredible. It was wartime and everyone was working and musicians had to entertain around the clock. We worked for Foreman Phillips, who operated a chain of ballrooms and nightclubs in the L.A. area. We’d play from 7pm to midnight at a ballroom in Baldwin Park, then we’d move to the Plantation in Culver City and pick ’til dawn. I stayed with Ray for a year or so until I went back to Cincinnati for a bit in 1945.

Now as for the recording, I did a couple of sessions with Wesley Tuttle in late 1944 and one with Shug Fisher in early 1945. Both of those were at Capitol. I did my first single with a vocal in California on the small Atlas label. The tune was “That’s All.” Cliffie recorded me singing Smiley Burnette’s “Hominy Grits” for the Beltone label. I also recorded with Porky Freeman for ARA. That was the boogie woogie number. They tell me that was the first boogie woogie on a guitar, but I don’t know if that’s true. It seems some of those black fellers were doing stuff with a guitar that sounded a lot like boogie woogie. Then it was back to Cliffie for those Tin Ear Tanner and his Backroom Boys sides. [Four sides were issued under that name with Merle on guitar, Tex Atchison on fiddle and vocal, Art Wenzel on accordion, Frank Marvin on steel, and Cliffie on bass and vocal.] The success of those sides got Cliffie hired by Capitol as that label’s country talent coordinator and chief assistant to country A&R man, Lee Gillette. He brought me, Tex Atchison, and others on board as salaried session men and recording artists

You said you went back to Cincinnati for a time in 1945.

MT: Mostly it was to visit family, check in with some old friends at the jamboree, and meet this new young talent they were talkin’ about named Chester Atkins. I asked him how he came to get that style, which involved using the thumb and two fingers and he said he thought that’s what I was doing. [Merle’s son Tom Bresh, who’s one hell of a picker in his own right, explains the difference between Travis’ and Atkins’ picking: “Merle played straight bass notes and alternated the notes only on chords. Merle liked the drive of that tonic on the bottom. He thought in four beats instead of two. Chet would boom chuck and Merle would four beat. He loved the four-beat rhythm player with the Count Basie Orchestra Freddie Green.”]

I also checked in with Syd Nathan at King Records. I was a sort of A&R man for King Records on the West Coast and I put about everyone out here who could pick, and wasn’t affiliated with anyone else on the King label. I put the Linvilles [Margie and Charlie], Curt Barrett, Jack Rogers, Jimmy Widener, Leon Rusk, Tex Atchison, and Jimmy Thomason all on King and we used side men like Noel Boggs, Harold Hensley, and Jimmy Wyble. Didn’t have a whole lot of hit records but there was some good pickin’ on a lot of them.

What did you do when you got back to L.A.?

MT: Well it was mostly more of the same. I got some work in some of those western pictures, mostly a song or two and maybe a couple of lines in each one; I started to make some of those Soundies, you know a song on film that played in a coin-operated machine. I did a couple more sides for small record labels like Globe [issued as Dusty Ward and his Arizona Waddies. Those small labels almost never used his real name] and I did a lot of radio, sometimes as many as four or five shows a day. Finally, I got signed by Capitol Records on March 18, 1946, and we kinda all got together to decide on how the Travis package was gonna work. That was the time, you know, when each country artist had a pre-packaged sound, so you’d know who the performer was going to be. Gene Autry, Ernest Tubb, and all the rest had a backup sound. Cliffie and Lee sort of decided on a sound for me that was kind of like Gene’s sound but a little bit peppier. The band would have a sharp muted trumpet, along with accordion, fiddle, steel guitar, and my guitar to keep the beat and take a break or two. I guess it worked okay as we kept that beat for the next five years or so. The first session I did I used Joaquin Murphy and Pedro de Paul from Spade Cooley’s band [on steel and accordion], this trumpet guy Jack McTaggart, who had worked with Stuart Hamblen, and Tex Atchison on the fiddle. We did four songs. Two of them, “No Vacancy” and “Cincinnati Lou,” became my first singles. The first got up to number two on the country charts [Billboard] and the second got up to number three. On the second session we did “Divorce Me COD,” which got to number one and “Missouri,” which got to number five. I guess we had arrived.

How did you come to record folk songs like “Dark as a Dungeon” and “Nine Pound Hammer?”

MT: Well, there was a bit of a folk music boom that was going on in 1946, particularly in the big cities like New York, and Capitol wanted in on it. Cliffie Stone called me and he said, “I want you to do an album of folk songs; this guy Burl Ives is killin’ ‘em over at Decca.” I told him that every folk song I know has been recorded by Ives or some of the old country guys like Bradley Kincaid. Cliffie said, “Well, write some.” I told him, “Cliffie, you don’t write folk songs,” and he said, “Well, write some songs that sound like folk songs.” I told him I’d have some ready the next day. He said, “Good, I’ll need eight.”

The next day I had one traditional number, “Nine Pound Hammer,” and three songs I wrote: “Sixteen Tons,” “Dark as a Dungeon,” and “Over by Number Nine.” I wrote the last two with a pencil on the back of an envelope while sitting on my motorcycle under a street light in Redondo Beach. Also on that album was “Muskrat,” which I got from Harold Hensley on the beach at Santa Monica; “I am a Pilgrim,” which I remembered from Mose Rager, whose brother got it from a black prisoner at the state prison; the old gospel standard “This World Is Not My Home.” We did “John Henry, the Steel Drivin’ Man” and I redid “That’s All” to finish up the eight. Then Capitol let them sit for two years before they issued them and by that time the folk fad had passed and the album went nowhere. Tennessee Ernie Ford discovered “Sixteen Tons” in 1955 and I was real glad about my fling as a folk singer. During the 1960s’ folk revival lots of folks rediscovered some of the other tunes on that set, so I’ve come to like those songs a whole lot.

How did you get into TV?

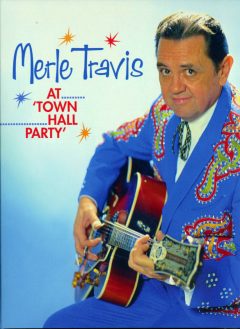

MT: Well, that would be with Cliffie, too. We’d done a whole lot of radio shows together like Hollywood Barn Dance, Western Stars, Dinner Bell Roundup, Radio Ranch, and finally Hometown Jamboree, which graduated to television in 1949, and I stayed with it for a couple of years between going on the road with Gene Autry, who I recorded with, and Hank Thompson, who I also recorded with. In the early 1950s I started to work with Foreman Phillips on a show he called the B-K Jamboree. It ran six hours every day in two three-hour shifts [on Channel 7 in L.A.]. Also on the show were Wes and Marilyn Tuttle, Johnny Bond, Eddie Cletro, Betsy Gay, Andy Parker and the Plainsmen, Jenks “Tex” Carmen, and Jimmy Widener. Phillips was always looking for new talent and I suggested Joe and Rose Lee Maphis, who came out and joined the show. So I was doing the B-K Ranch and also Cliffie’s Hometown Jamboree. It got so I was more on TV than off. I also did a show for a short time called The All American Jamboree. I sang and did comedy as a character called Rodney Dangerfield [this was long before Jack Roy used that name as a comedian]. In 1952, a new barn dance opened in Compton, called Town Hall Party and it picked up a good part of the cast of the old B-K Jamboree, including myself, Joe and Rose Lee, Wes and Marilyn, Tex Carmen, Judy Hayden, Johnny Bond, and added Les “Carrot Top” Anderson, Tex Ritter, and Eddie Dean [and over the years a whole lot more]. I stayed with that show thru out the 1950s until it came to an end in the early 1960s. Along the way I did several daytime programs [one with Cliffie and his gang, one with Johnny Bond and Wes Tuttle, and one with Judy Hayden, who was his then wife]. None of my own shows went over too well although people always said good things about them. It was always a better time on those barn dance shows, although I always felt more comfortable and at home in the studio shows on radio in the 1940s. I always felt I did my best work on those shows. In the studio I always felt someone else was in control of what I picked. On those old shows I always felt I was mostly my own boss in terms of what and how I decided to play. If I felt in a clownish mood I’d play clownish, if I was kind of down I could play a blues lick or two. So many times in those days I wouldn’t know what I was going to pick until I got up to the mic and that was kind of exciting, waiting to find out.

What about the folk revival? How did that affect you?

MT: Well, so many of you guys know my music and the things I’ve done better than I do. I get in front of a folk audience like those at the Ash Grove [L.A.’s most famous folk club during the late 1950s and 1960s], and people either want to hear the same old same old well-known stuff or they are calling for stuff I’ve forgotten and didn’t think that much of in the first place. I really am honored that people are as well acquainted with my music as they are, but sometimes I wish they’d let me pick what I want to.

Thank you for letting me talk to you as much as you have.

MT: Well, Lou, without longtime fans like you, it’d be a whole lot harder for an old Kentucky picker like me to get through this world.

I’d like to thank several people for helping out with this interview (or rather series of interviews). My father, George Curtiss, who hauled me to all those Town Hall Party and other country shows and may have suggested a question or two; Hank Penny and Cliffie Stone, who pointed me in the right direction; Hedy West; and the UCLA folk lore students, who were there and asked some questions that I forgot to ask. A lot more has been written about Merle by both folklorist and fan. He was a tremendously complex man who did not always have a happy time getting through this world, but that boy could pick like no one before or since. — Lou Curtiss