Yesterday And Today

Memories of Merle

Lou Curtiss interviews Merle Travis, Part I

When I saw Tom Boyer up at the Sam Hinton Folk Heritage Festival in June doing some of that thumb pickin’ made famous by all those Kentucky guitarists, it got me to thinking about maybe the most famous of them all: my favorite, Merle Travis. I grew up with Merle’s music starting with some of those old Capitol 78 rpm recordings my dad had, like “Sweet Temptation,” “Dapper Dan,” and a couple of others. When I moved to California in 1952, I was pleased to find out that Merle was all over L.A. television with his own show, with Cliffie Stone’s Hometown Jamboree and then with Town Hall Party. I got to see him in the movie From Here to Eternity and quite a few times at San Diego night spots like the Bostonia Ballroom. I even saw him sit in once with the Maddox Brothers and Rose at a club in National City. Merle saw me so many times that he started to recognize me and as I’m always searching for information, I started to ask questions and make notes. I wrote a couple of pieces about him for a high school journalism class and later did a couple of interviews with him backstage at one of the Town Hall shows. I got my first reel-to-reel (a Sony) tape recorder around 1956 and my second (a Uher, which was a lot more portable) in 1959. Sometime right about then I got Merle to sit down for an interview.

Later in 1964 I interviewed him again at the Ash Grove in L.A. It was around this time that I got copies of a couple of other interviews with him that were done by some UCLA folks. As part of this digitization project I’ve been involved in, I’ve been poking through tapes and writings, and I came across all of the Merle stuff kind of packed together. (I was probably thinking at one point about compiling it into something and just never got around to it.)

In addition to what I’ve already mentioned, Merle appeared at two of the San Diego Folk Festivals, the first time was at the second festival in 1968. On Saturday morning he gave a dynamite guitar workshop, then disappeared and we never saw him again. (Ten years later Smokey Rogers told me that he had met up with Merle at that festival and they went down to Tijuana together.) Merle was part of another Folk Festival a few years later and again, I got Merle backstage for a few questions. So here it is, the Merle Travis Interview. The questions are mostly by me; some are from the UCLA guys and questions about the early stuff are from a couple of high school buddies (maybe Dexter Sykes?). NOTE: folksinger Hedy West was real helpful in getting Merle to do the Ash Grove interview and she may have asked a question or two as well.

What were your earliest experiences with music and the guitar?

My Dad started me along. He was a coal miner you know, and he picked the five-string banjer. I was nuts about that when I was a kid, that old rappin’ style; the college kids all called it frailing. I learned that first when I was about six or seven years old before I ever picked up a guitar. Dad would play tunes like “Jeanie Weaver,” “Going Across the Sea,” “Ida Red,” “Moonlight on the Lake,” and a bunch of other pieces. Not a big repertoire of tunes like so many have today—didn’t have a whole lot of reason for it, but they could play for hours on end.

Were there many fiddlers around then?

Oh yeah, I got real hooked on fiddling, too. I use to try and play one. There was an old man named Uncle Merit Addison who lived down the road—we lived way down in the woods in Ebenezer, Kentucky. That’s where I was raised up. And Uncle Merit played the fiddle. I’d heard him play a couple of times with my Dad and others—I was about 10 years old then, and he was a pretty elderly feller, but I’d go up to him and say, “Uncle Merit, play me one on the fiddle.” He’d start to twist his wrist and say, “My ol’ wrist ain’t as nimble as it used to be, son.” But I’d bug him so much, he’d say, “Okay, crawl under the bed and get me up the fiddle.” And I’d crawl under the bed and get this old box that looked like a coffin and he’d unhook the latch and boy, would he play, so I decided that I’d be a fiddler just like Uncle Merit. Then my brother Taylor built a guitar and right after that, he moved to Indiana to take a job in a factory—anything beat coal mining. He wrote a letter back and at the end of it that said “Give Merle the guitar.” After that I took interest in the guitar.

Were there any guitar players you learned from?

Well, my friend Fuzz Gregory taught me some of the chords on the guitar, at least enough so’s I could back up my brother John Melvin’s banjer pickin’. And then I heard Mose Rager and Ike Everly [the Everly brothers’ dad] and saw what they were doing with that thumb and index finger syncopated style, and that’s what I had to play. Now, I never took a lesson from either of those guys but I follered them everywhere they went and just sort of picked it up. I also listened to other guitar pickers around the area, like Lester “Plucker” English, who was one of the best backup guys around and knew all those sophisticated “uptown” chords. Colie Addison taught me some tunes and ways of pickin’ them that I didn’t know, and there was the guy who taught Mose and Ike some, sort of the daddy of the Muhlenberg County guitar style and that would be Kennedy Jones who had played with Arthur Schultz [the black man who Bill Monroe gives credit for being an influence on bluegrass]. Jones was among the first to use a thumb pick to play the guitar. He was actually playing the Hawaiian steel when he first started using the thumb pick because he had a blister on his thumb [that was back around 1918], but he found out he got a real good bass accompaniment. Mose Rager says Jones created that multi-finger roll that we all use now.

Were you listening to records then?

Oh, yeah. We had an old Nick Lucas record that had “Pickin’ the Guitar” on one side and “Teasin’ the Frets” on the other. I played that record ’til the grooves was near wore off it. And I had records by Chris Bouchillion, the old talkin’ blues boy. If you don’t pay attention to the jokes he’s tellin’, you’re gonna hear some mighty fine guitar pickin’. I’d listen to the pop records too, along with the country, and I’d learn a tune from the Skillet Lickers one day and maybe Paul Whiteman’s Orchestra the next.

What was your first paying job as a musician?

Well, I was walkin’ home from a Brush Arbor meeting with Mose Rager’s younger brother J.R. and his cousin Guy Lester, and right outside the home of Billy Bridges, the operator of the Black Diamond Mining Company Guy starts singing the old pop song “Shine on Harvest Moon.” Well, all the lights came on, and I figured we was all going to have to run, but ol’ Billy came out and thanked us and gave each one of us 50 cents. So I figured, well, maybe there’s something more than a good time to this here makin’ music, and I judged that that was one kind of life I wanted to have.

Well, how did you start in as a professional musician?

I started out local playin’ at play parties and dances. I quit school after the eighth grade. It was during the Depression and I figured I had to start makin’ my own way. My folks weren’t none too happy about that, but by 1935 I was out hoppin’ freight trains and playing on street corners to make some money. I’d seen Clayton McMichen and his Georgia Wildcats a few times and even got to know Carl Cotner who played in the band and wanted me to but that hadn’t happened yet. I went up to Evansville, Indiana to visit my brother Taylor and hooked up with a band called the Tennessee Tomcats and played on the radio for the first time, WEBS in Evansville. I made about 30 cents a show and lived on nickel hamburgers and orange pop. Didn’t last with them long. I moved on to the Knox County Knockabouts and briefly with a group called the Drifting Pioneers. Finally, I got news from my Mother at home that a telegram had come from MacMichen to meet him in Columbus, Ohio on March first. That was 1937.

What was it like playing and working with MacMichen?

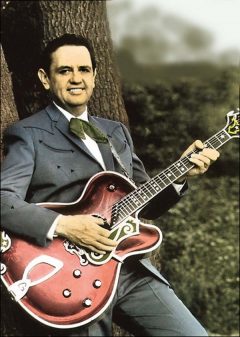

Well, he called me Ridgerunner and always gave me a featured tune on the show, something like “Tiger Rag” or “I’ll See You in my Dreams.” When Riley Puckett [the blind singer guitarist who had worked with MacMichen in the Skillet Lickers back in the 1920s and early 1930s] came out with us for a show it was my job to sort of be his lead man and help him get around. That was okay with me since here was another guitar man I’d listened to on records for years and now I got to see and pick with him in person. I’ve found that every guitar picker I’ve ever known had something I could learn from. I don’t think you ever stop learning how to pick a guitar. A lot has been made of me working with Mac, but actually I didn’t stay with him very long, only a few months and by late summer I was back in Evansville with the Drifting Pioneers. I think the reason so much has been made of my time with Mac is because of that real good band picture we had taken with my old Gretch Model-30 guitar in it. That photo has been in more picture books and magazine articles than you could shake a stick at.

What was your first big Barn Dance show?

Well, the Driftin’ Pioneers first tried to get it goin’ in Chicago. We were a pretty good band with fiddler Sleepy Martin, mandolin player Walter Brown and his brother Bill on the bass, and me on guitar. We just never seemed to get beyond the guest shot stage in that city, but Bob Atcher, who we got to know pretty well, phoned George Biggar at WLW in Cincinnati, Ohio, and they were settin’ up a new barn dance show named after the Kentucky county across the Ohio River from Cincinnati and that’s how we got on the Boone County Jamboree. That was in 1939 and along with us they had Lazy Jim Day, Captain Stubby and his Buccaneers, Ma and Pa McCormick, Hugh Cross, Shug Fisher and his Radio Pals, Helen Diller, and Georgia Brown. Then, later on, there was Joe Maphis, the Delmore Brothers, Bradley Kincaid, Grandpa Jones, Ramona Riggins [later Jones after she married Grandpa], Curly Fox and Texas Ruby, Roy Starkey the singing cowboy, and a young man from California named Wesley Tuttle who became a friend for life.

When did you first hear Joe Maphis and what did you think of him?

Fastest hands in the business. I don’t think he’ll ever be equaled in that department. I first heard Joe when he was with Sunshine Sue Workman at WRVA in Richmond, Virginia. I’d listen to him every opportunity I got. When he came to WLW in 1943 or so, I found out he’d been listening to me on WLW. We struck up a friendship right away.

How long did you stay with the Drifting Pioneers?

We were together for seven years, most of that time on the Jamboree. The war— like it did all things about that time—broke up the group, but I stayed with the Jamboree as a solo act and with Grandpa Jones and the Delmore Brothers as the Browns Ferry Four, singing gospel songs and other quartet stuff like old Mill Brothers and Ink Spots tunes. During the war years Texas Jim Lewis and Smokey Rogers came to WLW for awhile before headin’ west, and so did Charlie and Kate Linville. Smiley Burnette came on for awhile and Hank Penny brought his Radio Cowboys up from Atlanta and stayed on as a solo comic and picker for awhile. Hank also led the Plantation Boys with another great guitarist, Roy Lanham. Hank talked me into trying my hand as a comic for a time. I worked out a character named Possum Gosset, but it was too much like some of the folks I knew back in Ebenezer and I gave it up. [NOTE: Joe Maphis and Hank Penny told me they tried to get Merle to revive the character out in California as it was one of the funniest and most original they’d seen but he never would.] I didn’t want to hurt anyone’s feelings.

How was it being on a show like Boone County?

Well, you know Cincinnati isn’t exactly known for its rich and varied night life. Mostly it was sittin’ around pickin’ and going out drinking. With Alton and Rabon Delmore around, there was no shortage of knowin’ about drinking places. They knew them all and the rest of us just tried to keep up. I started to hang around Sid Nathan’s Record Shop on Central Avenue, particularly after the Browns Ferry Four got started. I was looking for those old black gospel quartets on record so we could steal stuff for our group. I’d buy records by groups like the Golden Gate Quartet and the Heavenly Gospel Singers, most any quartet with the word Jubilee in it. That was gonna be stuff we could use.

Sid Nathan was thinking about starting a record label about this time and sort of recruited me and Grandpa as his first artists. WLW had a strict rule about any of their radio contracted artists doing anything for anyone else and that included making records. So Sid put us out as the Sheppard Brothers. The songs, I believe, were “The Steppin’ Out Kind” and “You’ll Be Lonesome Too.” He called his label King Records ’cause he said it was gonna be king of them all. I also did a couple of solo sides that Sid put out as Bob McCarthy. [NOTE: the titles were “When Mussolini Laid his Pistol Down” and “Two Time Annie.”] I guess they came out, but I don’t remember ever seeing one in a store anywhere. [NOTE: In 40 years of running a collector’s record shop, I’ve never come across a copy of either one. They remain among the rarest of the rare but they were the start of King Records, which became one of the leading independent rhythm and blues and country and bluegrass labels in the 1940s and 1950s.]

How did you happen to get out to the West Coast?

Well, I was with the Marines for a time and when I got out, I resumed playing at WLW, did another session for King backing Grandpa on a couple of tunes [NOTE: “It’s Raining Here this Morning” and “Eight More Miles to Louisville”] and did a couple of my own. Grandpa was going in the army, Joe Maphis had moved on to WLS in Chicago, the Delmores had moved on and so had the Linvilles [who had moved to California]. I met with Smiley Burnette who was doin’ a show in town and he was ravin’ about California and how there was so much work for musicians out there. So on March 1, 1944, I borrowed $10 from about six WLW musicians and just took off. I started off to visit Joe in Chicago and told him I was going to California to seek my fortune, and that’s just what I did. Joe loaned me an extra $25 to get me on my way. I never forgot all those folks who loaned me money. I paid every one of them back and I hope I’ve shown them all how proud I am to have them as friends. I took the train to L.A.—ate sandwiches, slept sitting up, got into town, and crashed at a flophouse across from the station. The next day I called Wesley Tuttle, and he came and got me and took me out to his house in the San Fernando Valley. The next day he called the Linvilles and took me down to Stuart Hamblen’s radio show where I appeared as a guest. He also took me over to a movie set where I met Tex Ritter and just a couple months later I was in a studio backing Tex on his hit “Jealous Heart.” I was also playing with Ritter on shows, as well as with Charlie and Margie Linville, Al Dexter, and Texas Jim Lewis. I was also singing on CBS radio in a trio with Wes Tuttle and Jimmy Dean. [NOTE: not the sausage-selling Big John guy, but the older brother of movie cowboy Eddie Dean.] At the “Jealous Heart” session at Capitol Records I met Cliffie Stone [who played bass in that session]. Cliffie was a mover at Capitol and had been an L.A. radio personality since the mid 1930s. He was just the guy I needed to meet to get me goin’ on the L.A. scene.

Reprinted from San Diego Troubadour, July 2007. Next month: Part Two: Merle Travis, the next 20 Years—From Session Man to Country Music Legend.