Yesterday And Today

Lawrence Ferlinghetti: America’s Poet

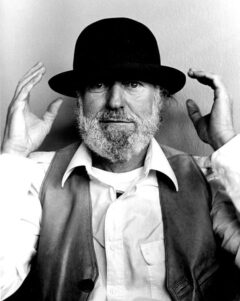

Lawrence Ferlinghetti passed away last month, at age 101, and what we’ve lost is a great American voice. His poems were written in a wonderfully amorphous American idiom, his rhythms were light, quick, jazz-like; his patois seemed to come from anywhere in 50 states. His poems were vocalizations of the man on the street who appears to be always next to you at the end of the bar, on the subway car, the city bus, in line for a hot dog at a ball game; he’s the guy holding a picket sign in front of city hall, speaking with a tone that’s sturdy but quickly uttered, starting in one area with an observation but morphing through the chain of associations to areas you didn’t know were related in any way. You read him, you listened to him read, you were never sure where the poems would go but you knew there would be a point, an irony, a moral certainty there, tempered with good humor.

Being based in San Francisco and proximity to the city’s edgier literary community, Ferlinghetti is often grouped with the generation of Beat writers and poets who flourished in the 1950s. He balked at the inclusion, remarking that he was “…the last of the Bohemians rather than the first of the Beats.” Even so, it’s arguable that he did more than anyone else to usher in the Beat Era in the ’50s with his Pocket Poets Series, printed under the City Lights imprint. The first in the series was own book, a 1955 poetry collection called Pictures of the Gone World, with subsequent volumes introducing the world to Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Anne Waldman, Frank O’Hara, Gregory Corso, and many other voices—Beats and non-beats, who poked holes in the quilt of Eisenhower’s America. In 1956 the publication of Ginsberg’s Howl and Other Poems found publisher Ferlinghetti in court on obscenity charges, due to Ginsberg’s frank and comparatively specific depiction of homoerotic content. With the aid of the ACLU, Ferlinghetti won the case and continued to publish and nurture writers from the margin’s society with his press and bookstore and extended his own writing further into the soul of America, a great country that has done remarkable things but that could do far better. He was writing that he was waiting for the promise of freedom and justice for all to come to be fact, not fantasy. His activism revealed a character that wouldn’t abide by the idea that the Artist was removed from the public, inoculated against controversy. He knew that art wasn’t a commodity to insulate citizens from the harsher facts of war, racism, and poverty; his poems didn’t blind us with banality. Art was not a thing to make us “feel good”; it was a way to make us feel, fully and painfully if need be. It was a tool to nag, prod, provoke, and elicit a response to get readers out of their seats and into the streets to work for that Better Day. Many an effective activist from the era had their moral compass fine-tuned and enhanced by the effusive, chatty, and astute poems of Ferlinghetti and the quarrelsome songs of Phil Ochs, Bob Dylan, and Woody Guthrie.

Lawrence Ferlinghetti thought about things he liked and even more about things that bothered him, that bothered millions. He was a worldly man, the man who lived in the upstairs apartment, who owned the shop on the corner; he was a citizen poet. His persona was a sublimely self-effacing Everyman, less grandiose and bombastic than Whitman, wittier than others by far, the man in a government waiting his turn at the DMV, for jury duty, and while he waits, he muses about what else he and the rest of us are waiting for besides for our numbers to be called.

I am waiting for my case to come up

and I am waiting

for a rebirth of wonder

and I am waiting for someone

to really discover America

and wail

and I am waiting

for the discovery

of a new symbolic western frontier

and I am waiting

for the American Eagle

to really spread its wings

and straighten up and fly right

and I am waiting

for the Age of Anxiety

to drop dead

and I am waiting

for the war to be fought

which will make the world safe

for anarchy

and I am waiting

for the final withering away

of all governments

and I am perpetually awaiting

a rebirth of wonder

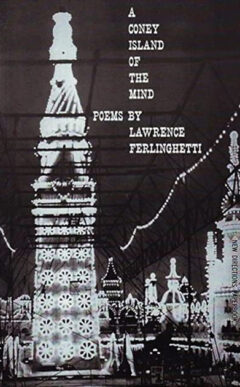

—Excerpted from “I Am Waiting” by Lawrence Ferlinghetti (from A Coney Island of the Mind, 1958).

Lawrence Ferlinghetti is the greatest public poet America has in the second half of the 20th century. Poet, novelist, playwright, travel writer, bookseller, and publisher of the revered City Lights Books press, Ferlinghetti wasn’t a dry academic composing intangible lines of verse about impossible metaphysics. His feet were on the ground along with those of his fellow citizens, trudging and grunting along that road, a man with an unshakeable belief that the world can be made better even although a “perfect one” seems beyond our reach. He wrote to his reader’s ear, seeming less to intone from the deadness of the page and more to speak to you directly. “In Goya’s Greatest Scenes,” one of his best-known poems from his landmark 1958 poetry collection A Coney Island of the Mind we hear the unique voice again, leaning over to our ear and remarking, sotto voce:

In Goya’s greatest scenes we seem to see

the people of the world

exactly at the moment when

they first attained the title of

‘suffering humanity’

They writhe upon the page

in a veritable rage

of adversity

Heaped up

groaning with babies and bayonets

under cement skies

in an abstract landscape of blasted trees

bent statues bats wings and beaks

slippery gibbets

cadavers and carnivorous cocks

and all the final hollering monsters

of the

‘imagination of disaster’

they are so bloody real

it is as if they really still existed

And they do

Only the landscape is changed…

Lawrence Ferlinghetti writes in the tradition of the public poet, no less than Vachel Lindsay or the wonderfully expansive Whitman; he is less a man to complain about how the world doesn’t fit comfortably around the skin he was born in or muse long and serially on fragments of memory and half-recalled cliches that never crystallize as a perception. His poems are a force of personality that eschews introspection and opts instead to verbalize, extol, berate, rant, and rave in a lyrical vein at once cranky, ecstatic, lustful, and very much in love with the senses that bring him the full force of the beauty and ugliness that is life. Ferlinghetti was not a ruminator, a worrier, an introvert, a sad soul contemplating many shades of despair. He didn’t decorate the walls of his inner life with gloom. There is no melancholic wallpaper in the world the poet finds himself in, there are no metaphysics of gloom and regret. We need to recall that one of his poetry collections was titled How to Paint Sunlight. Not that Ferlinghetti’s poems are bluster or weakly transpired musings on a beauty obscured urban density—his lines are confident, sure, idiom-matching rhythm, not lapsing into a self-parody of hip argot except when he deigned to do so. His images are fresh and electric, encompassing emotions and the consequence of things done to seek truth, beauty, a reason to celebrate the fragile miracle that is life.

There is little in the way of introspection, and that, I think, is the secret of his endearing popularity, and why his poems remain readable decades after the Beat craze passed on into history. He is poet who—like a good friend, a very good friend—talks to you at the bar and pokes you in the shoulder; the man who won’t let you get away with lying to yourself—his poems are the second opinion you constantly get, like it or not, which is a crude but freshly phrased thing we can call the truth, of a sort. It is, I think, a voice attached to an imagination that realizes there are not enough years in any lifespan not to live fully, senses engaged with the raw stuff of existence.

These poems are jazzy, a crafted idiom that rings with the swinging chain of associations that cut through reams of rhetoric and regulation and get to the pulsing heart of the matter: birth, sex, death, joy, sorrow, glee, calamity. It all hurts, it all brings sensations we don’t want, but this is a man who rolls with the punches, knows when to duck, writes as though he’s astounded that he’s still drawing a breath and walking still without a crutch or cane, that he has a voice to speak words of yet new seductions to come or are already underway. It’s worth noting that there was a selected-poems edition of his work published in the ’80s called Endless Life, which included a section of newer works, including a long piece that serves as the collection’s title.

What interests me isn’t so much the quality of the poem but the concern it expresses, to stay engaged with the doings of citizens he shares the planet with, to keep doing what a poet should be doing at all times when he chooses to poke his muse and write in those irregular line breaks that are most people’s idea of what poetry is. Even as he ages and friends die and institutions and personalized traditions come to an end, the world goes on with things to do, people to know, controversies to become a part of. The conversation doesn’t end until the tongue can no longer flutter about, the eyes cannot see, and the mind cannot parse.

I am signaling you through the flames.

The North Pole is not where it used to be.

Manifest Destiny is no longer manifest.

Civilization self-destructs.

Nemesis is knocking at the door.

What are poets for, in such an age?

What is the use of poetry?

The state of the world calls out for poetry to save it.

If you would be a poet, create works capable

of answering the challenge of apocalyptic times,

even if this meaning sounds apocalyptic.

You are Whitman,

you are Poe,

you are Mark Twain,

you are Emily Dickinson

and Edna St. Vincent Millay,

you are Neruda and Mayakovsky

and Pasolini, you are an American or a non-American,

you can conquer the conquerors

with words….

From Poetry as Insurgent Art by Lawrence Ferlinghetti

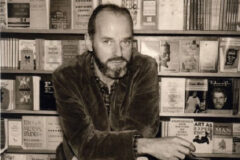

The first time I saw Lawrence Ferlinghetti was during a pilgrimage to San Francisco with two other writer friends of mine in the mid-1970s. The three of us (Steve Esmedina, David Zielinski, and this guy) were eager to garner some literary authenticity by visiting the places where famous scribes read. City Lights in North Beach was our first stop, and it was something of a surprise when we walked into the crowded shop, to see Ferlinghetti behind the front counter chatting with customers, answering the phone, and ringing up sales.

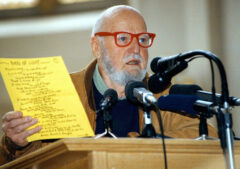

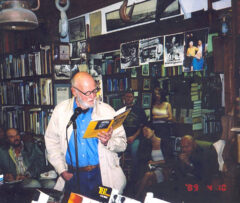

The last time I saw the poet was in 2005 at D.G. Wills Books in La Jolla, where I was working. Ferlinghetti had just published a new book, Americus Book 1, something of a continuous, epic-length poem, which he described as “part documentary, part public pillow talk, part personal epic—a descant, a canto unsung, a banal history, a true fiction, lyric and political,” combining “universal texts, snatches of song, words or phrases, murmuring of love or hate . . . that haunt our nocturnal imagination.”

Ferlinghetti reading at D.G. Wills Bookstore in 2005.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7XaIj7eR7kU

Whatever this turns out to be, it was an inspired summing up of the spiritual state of American affairs, a bittersweet and often comic recollection of the poet’s long journey and long life on the front lines of culture and politics. He was the featured poet at the 2005 Border Voices Poetry Fair at San Diego State University, an event organized by poet and journalist Jack Webb. D.G. Wills Books had previously hosted Beat poets Gary Snyder, Allen Ginsberg, Michael McClure, and Ted Joans, and Wills had the idea that having Ferlinghetti read at the bookstore would be a fitting and important addition to the roster of poets and writers who had read in the past. Wills contacted Webb and arranged, with Ferlinghetti’s approval, to have the Maestro read at D.G. Wills Books following his appearance at San Diego State.

As expected, it was a wild and crowded scene, every seat in the bookstore filled with, poets, fans, and the merely curious. The front and side doors of the shop were open, an outdoor PA was mounted, and chairs were set up for attendees unable to sit inside. It was a crowd nearing three hundred. It was a cramped situation where everything that could go wrong didn’t—except one thing. To be sure, there’s always one thing that goes askew. In the flurry of overseeing the set up and directing the volunteer staff, Wills forgot to disconnect the business phone. Twenty or so minutes into the reading, Ferlinghetti is reading an especially lush passage from Americus and the audience is leaning toward him to heart, there is a pause, an intake of breath, Ferlinghetti begins to read again. Then the phone rings.

Wills was at the end of the store’s front counter and pounced on the phone before it could peal again. Ferlinghetti didn’t miss a beat. “Is this Manny’s Bar and Pool Hall?” he asked. The accent was East Coast, New York perhaps, American. The audience inside and out gave a nice laugh. Lawrence Ferlinghetti grinned and continued to read, the man who will continue to be read in bars, pool halls, bus stops, libraries, quoted in academic papers and by bus boys and waitresses.