Yesterday And Today

JERRY RUBIN: DiD iT! A Walking Contradiction–From Yippie to Yuppie

It is damn near impossible not to be a reactionary in the modern-day world; depending upon what sort of historical/hysterical constructs you embrace. And it is arguable in our current state of world affairs that a reactionary and a revolutionary are opposite sides of the same coin. One group wishes to revert to a previously cherished status quo and the other wants to abolish the status quo altogether. Both sides desire a radical reformation of social order, based on their own tribal ideology and values. That is the essential dichotomy of what we might call the political landscape, then and now.

As a nation that is more privileged than most, we should thank our lucky stars that we still have the concept of the First Amendment in the U.S. Constitution. “Free Speech” is about the only thing in this country that is free, even though it comes with the caveat of responsibility and consequences. We throw around the terms “freedom” and “democracy” in this culture like a Frisbee on a summer’s day, but was there ever a time in antiquity when human beings were truly “free,” i.e., self-governing and in complete control of their individual destinies without the interference and/or repression of the state, the church, or the crown? Of course not. But that doesn’t mean we haven’t given it the old college try throughout the ages to correct the situation. The primary challenge of the human race remains: What is the right course of action for us to take as a collective? And upon whose paradigm do we base that right action?

Next year will be the 50th anniversary of one of the tumultuous years in American history: 1968. Everyone over the age of 12 ought to know that it was the year that Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert Kennedy were assassinated. It was the year that Lyndon Baines Johnson abdicated his position as the figurehead of American politics to be succeeded by Richard Milhous Nixon. Selective Service in the United States, aka “the draft,” was mandatory for the majority of young men, between the ages of 18 and 25, in order to serve as cannon fodder for the Vietnam War. It was a time of grim, meat-hook realities as young people came to understand that their very lives hung in the balance, while supporting the racist policies of the military industrial complex. A generation of young Americans was waking up from the institutional brainwashing that promoted blind faith and jingoistic acquiescence to the practice of governmental genocide. For those who value the sanctity of life and the ability to exercise their free will, those mandates to support war by institutionalized fascists were unacceptable and deserving of reproach.

As contradictory as it may sound, you could say that 1968 was a time of reactionary revolutionaries. You can hear it in the visceral battle cries of rock groups like the Doors, Jefferson Airplane, and MC5, kicking out the jams against the American ruse of spreading or saving democracy, and standing up for the equality of all peoples–offering no quarter and demanding change now. The term “generation gap” came to represent the clash of values that one group of people embraced (“conservatives”) in opposition to those who insisted on a violent revolution to overthrow the antiquated regime of fossils and fools–a classic representation of the Us vs. Them paradox. You’re either part of the problem or part of the solution goes the rhetoric of the times.

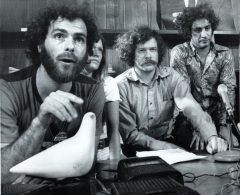

1968 was also the time when “the whole world was watching” and a blood bath erupted in the parks and streets of Chicago, Illinois, when the goon squads of Mayor Richard Daley’s jackbooted police force came out violently en masse against the protesters who had organized a “Festival of Life,” as a contrast to the “Convention of Death” by the politicos of the Democratic National Convention, who had officially come out in support of the war in Vietnam. One of the principal architects of the Festival of Life event was anti-war activist Jerry Rubin, who, along with Abbie Hoffman and six other members of the “Chicago 8,” was ironically convicted of “crossing state lines with the intent of inciting a riot” as a result of these confrontations, though those convictions were overturned on appeal. It was a galvanizing moment in American history, and it symbolized the diabolical lengths the establishment in this country was willing to go to suppress the dissent of its citizens against globalist, war-mongering psychopaths.

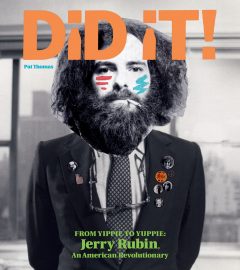

For many reasons, Jerry Rubin is a pivotal cultural figure of the 20th century, and, remarkably, the episodic antics of his life’s journey have never been told by a biographer…until now. Pat Thomas–musician, archivist, and author of the acclaimed multi-media project Listen, Whitey! The Sights & Sounds of Black Power 1965—1975–has, with the full cooperation of the Rubin estate, assembled an epic, sweeping overview of Rubin’s life titled DiD iT! From Yippie to Yuppie: Jerry Rubin, An American Revolutionary. DiD iT! is an extraordinary piece of work, and it deserves a pride of place upon the shelf of every thinking person who wishes to deepen their understanding of the contextual complexities of radical American politics in the 1960s and ’70s.

There are no two ways about it: Jerry Rubin is a polarizing figure. Across the brief span of 56 years, Rubin embodied many of the contradictory aspects of what it means to be a human being and an American. In fact, that’s exactly how he described himself on the Phil Donahue Show in April of 1970, as “a walking contradiction,” asking Donahue “can’t you understand contradictions?” He was profane and sacred; a traitor and a patriot; a Marxist and a liberal democrat; an idealist and a pragmatist; a radical and a conservative; a man of integrity and a sell-out. Rubin was the complete personification of antithetical complements–in short, an enigma deserving of scrutiny.

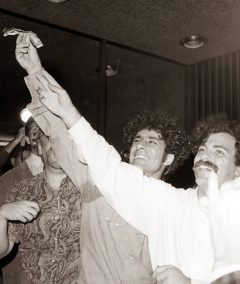

Rubin was a master manipulator of the media, who made inflammatory speeches, pumped his fist in the air, linked arms with his fellow comrades, and ended up pissing off a LOT of people as he evolved into a counterculture icon. Through the “treasonous” acts of stopping troop trains in Oakland, California, and the conceptual tomfoolery of “levitating the Pentagon” in Arlington, Virginia, to conducting networking business salons in New York City in the 1980s that were the complete antithesis of his youthful, radical persona. He was a cultural chameleon who went from a Zapata-mustachioed revolutionary to a bearded Berkeley radical to a clean-shaven businessman in a Brooks Brothers suit. Rubin was a Kokopelli trickster who resisted classification, and he was not to be trusted.

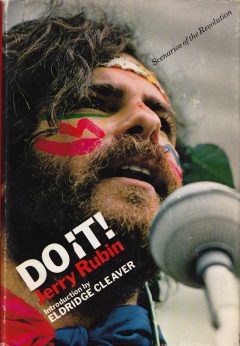

The book’s subtitle From Yippie to Yuppie is a turn of phrase foisted upon Rubin in the 1980s after reinventing himself through a number of very public transformations. The flashpoints of Rubin’s life are captured through the three autobiographical tomes that he penned: 1970’s DO iT! Scenarios of the Revolution, 1971’s We are Everywhere, and 1976’s Growing (Up) at 37. As revelatory as these confessional diatribes can be, they are somewhat myopic selfies of a man in constant motion, and they don’t begin to capture the full range of Rubin’s activities and associations. It would take an (somewhat) objective outsider to fill that role, and Thomas does it with passion.

Thomas’ publisher, as with the Listen, Whitey! project, is Fantagraphics Books, highly respected for their comic book anthologies. DiD iT! has a sprawling, scrapbook feel, as if you are going through a shoebox in Rubin’s closet, sifting through his diaries, journals, photographs, and newspaper clippings. There are numerous sidebar detours, which occasionally disrupt the central narrative. The excessive magazine-style pull quotes are a bit redundant to the main body of text, but that’s a minor editorial quibble. Generally speaking, the book looks sensational. It’s an unconventional tribute to a supremely unconventional character.

During a five-year period, Thomas interviewed over 75 of Rubin’s associates: Yippies, Chicago 8 defendants, participants of the Berkeley Free Speech Movement, and members of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). DiD iT! includes correspondence with Norman Lear, Norman Mailer, John Lennon and Yoko Ono, Eldridge Cleaver, and the Weathermen. It also trawls through Rubin’s personal relationships with Allen Ginsberg, Phil Ochs, Bob Dylan, Timothy Leary, Charles Manson, Mick Jagger, and other figures of the era. And, most important, it explores the misunderstood relationship between Rubin and his partner-in-crime Abbie Hoffman, with insights into their Yippie vs. Yuppie debates.

The chapter headings give the big bullet points of Rubin’s life: “The Making of a Revolutionary,” “The Birth of Yippie,” “Chicago ’68,” “The Trial,” “The Dream is Over: the End of the Movement,” “It’s the Beginning of a New Age,” “Yuppie,” and “Jerry’s Legacy.”

Certainly one of the more interesting chapters in DiD iT! is chapter nine (“number nine, number nine”) titled “Christ, You Know It Ain’t Easy: The Ballad of John & Yoko, Rubin & Sinclair & Peel & Weberman & Dylan.” As John Lennon wrote circa 1978 in Skywriting by Word of Mouth: “Upon our arrival in the U.S., we were practically met off the plane by the ‘Mork and Mindy’ of the Sixties–Jerry Rubin and Abbie Hoffman–and promptly taken on a tour of New York’s ‘underground,’ which consisted mainly of David Peel singing about dope in Washington Square Park. Jerry and Abbie: two classic, fun-loving hustlers. I can do without Marx and Jesus.

“Mae ‘They’re Coming Through the Windows!’ Brussel and Paul Krassner told us that Jerry and Abbie and the whole of the Chicago Seven [sic] were double agents for the C.I.A. (except Krassner, of course). We never did find out.

“The thing that bothered most of our revolutionary brothers was the fact that we weren’t against anything, just for things, you know, like peace and love and all that naïve crap. That was not macho enough for the tough Jewish Haggendass (not the ice cream). I mean, man, they were the Chicago Seven and knew the Black Panthers. Whilst they tried to ‘use’ us, we tried to ‘convert’ them. We even got them on The Mike Douglas Show, but none of them knew how to talk to the people–never mind lead them! All in all, we had a few laughs and a lot of drugs.”

“First of all, I love John Lennon as much as anybody,” says Thomas. “But John Lennon, in my book, is an asshole of assholes. Lennon spent that last eight years of his life rewriting his history. He couldn’t wait to meet Jerry and Abbie. He’d seen Rubin on the David Frost Show in England when Rubin shut the show down. Basically, there was a mutual admiration society going on. He’d already written ‘Power to the People,’ and when he got to New York he was ready to plug in. What Lennon did in that last part of his life is say: those guys hoodwinked me. And as Rubin said, dude you’re an adult. No one put a gun to your head and said hang out with Jerry Rubin for the next two years. No one put a gun to your head and said let’s get Nixon out of office. Lennon needed to own his politics. And Lennon, just like Rubin, when he’s into something, he’s really into it. He later denounced Some Time in New York City, which is one of my favorite Lennon albums. But at the time, that was who he was. And Jerry was a very big part of that. So, it’s going to piss off a few Lennon fans.”

************

Born in 1964, in Pennsylvania, Pat Thomas is a classic nonconformist who came of age in southern New York. “I didn’t really fit in at high school,” he says. “I actually quit in the tenth grade, enrolled in a community college, graduated a month after my eighteenth birthday with a two-year degree in electronics, and got offered a gig with Eastman Kodak in Rochester. People know me from Rochester because I was a drummer in this band called Absolute Grey, and we did three or four albums.” After Absolute Grey disintegrated, Thomas spent a year in Denmark, and then moved to the Bay Area for the next 22 years.

“My book Listen, Whitey! got written out of a mid-life crisis depression. I was in my mid-40s, and although I had produced a lot of reissues, and I’d certainly recorded a lot of my own music as Absolute Grey, Pat Thomas, and Mushroom, somehow I felt like I hadn’t done anything–even though I had done a fair amount. And I decided to go back to college, get my American studies degree and write Listen, Whitey! all at the same time.

“At 44, being in college as an adult is a totally different thing, because I was there to do some learning. And because I was going to college in Oakland I became very interested in the Black Panthers. And I got very lucky, because I was buying various Panther books, reading them, and then having lunch with David Hilliard, who had been chief of staff of the Panthers in their heyday. It was this incredible master class of reading a specific book about the Panthers and then getting his feedback in order to capture the feeling of the Panthers. Arguably, Listen, Whitey! is not a definitive history of the Panthers, it is really about the music.

“I wound up moving to Seattle from Oakland in 2009 to hang out with my friend and editor Kathy Wolf, and she was the one who encouraged me to go to Evergreen State, where they run their bachelors program like a masters program. So I managed to work on Listen, Whitey! while I was working on my degree–Kathy got me my book deal with Fantagraphics. I also started writing the Jerry Rubin book at Evergreen.

“One of the things that made the Rubin book difficult to write is there’s three Jerrys. There’s the Yippie Jerry; there’s the New Age, self-help Jerry; and then there’s the Yuppie/entrepreneur Jerry. One of the reasons why the estate green-lighted this project is they quickly realized that I was willing to give equal consideration to all three Jerrys. Jerry was sort of a leader in two out of those three movements. He was obviously a Yippie/anti-war leader. In the New Age movement he was a little bit of a spokesman, using his fame from the ’60s and doing interviews in Hustler and Oui, interestingly enough, and some New Age magazines. And then in the Yuppie movement he was definitely a leader. He was using the phrase ‘social networking’ long before there was a Facebook or LinkedIn, and he was holding these weekly parties in places like Studio 54 and encouraging people to trade business cards. It was like a real-time, analog, reel-to-reel version of Facebook and Linkedin.

“Some people criticize him for those parties, but Jerry was sort of unhirable. He was a big personality, and also people didn’t trust him–he was the guy who threw money onto the stock exchange in ’67, so if we let him work at our company how do we know he’s not going to open the vault and tell everybody to take some money or something? So he was damned if he did and damned if he didn’t in terms of all these various pursuits. So he really had to be self-employed in the 1980s onward.

“And because both of his parents died when they were about 50 from cancer and other diseases, he was obsessed with living past 50. He didn’t make it to 60. He became obsessed with vitamins and health food. And he was marketing a vitamin drink that was probably a lot of caffeine, called ‘Wow!’ I’m not saying I love him for doing that, but that was his bag, and compared to what’s going on today he sure ain’t Mitch McConnell. Jerry became an entrepreneur, but he didn’t become a right-winger. But let’s be clear: being a lefty doesn’t necessarily mean that you’re a nice person.

“Here’s the deal: the Chicago 8 trial, for as much of a media circus as it was, and for as many laughs that Jerry and Abbie and the others had, was a real trial, and the government was determined to put these guys away for life. So after the trial, Jerry and Abbie really thought that with the help of John Lennon they could galvanize the youth movement and vote Nixon out of office. And when that didn’t happen on the night of the ’72 election, Lennon himself had a little bit of a nervous breakdown, and Jerry realized that the ’60s were definitely over. So, Jerry did what he needed to do, which was after many years of dedicating himself to the movement, he took care of himself. He moved to San Francisco, he started doing yoga, started eating health food, got involved in est, which I know a lot of people think is criminal. But my point is, it’s not a crime to do a little self-help. And, frankly, half of the obnoxious assholes that I deal with on a daily basis need a lot of self-help. And so Jerry spent a few years reinventing himself.

“People forget how young the Panthers and the Yippies were. There was a naïveté, and there was also a youthful bravado that those guys had. I’ve met a lot of 20-somethings over the last 40 years, and very few of them had the bravado of a Huey Newton or Jerry Rubin in 1968. And that’s sort of the beauty of youth. And that also leads to mistakes. Would an older Huey Newton or an older Jerry Rubin make different decisions? I’m sure they would. But, again, it’s easy in 2017 to say, ‘Well, if I’d been in Chicago at the ’68 convention I would have done this.’ Well, you weren’t.

“I’m not saying that Jerry was the most wonderful human being that ever walked on the face of Wall Street. But one of the subtexts of my book is: most critics of Jerry Rubin are guys who followed relatively the same path. You drop out of college in ’68 and join the revolution. By ’73, ’74 you go back to school, you get a master’s degree, you get married, and you have some kids. Now you’re living in Westwood, you’ve got two Mercedes in the parking lot, and now you’re saying that Rubin is a sellout? No. Rubin did exactly what you did, except that he’s ten times more famous. The trajectory of Rubin is the trajectory of most Baby Boomers. Very few Baby Boomers did what Abbie Hoffman did, which was stay an activist all the way to the end. Most did what Rubin did.

“I just said many of us are Jerrys–actually, we’re not really Jerrys, because many of us bitch and moan and don’t really change. Jerry was proactive. And I saw a lot of myself in Jerry as I was writing the book, although I never met the man.

“Jerry was a doer–I mean, there is a reason why his book is called DO iT! And there’s a reason why my book is called DiD iT!, because he fucking did it! You can never accuse Jerry of just sitting around and whining and doing nothing else.”

Tuli Kupferberg of the Fugs: “If you reflect on it, whatever Jerry’s faults were, a lot of them were the faults of the Sixties. The movement collapsed, Jerry collapsed. The movement ‘sold out,’ in quotes; Jerry sold out, without the quotes. But actually he didn’t really sell out. He never bought in. So in a way he’s typical of the whole stream of the Sixties–the superficiality. Jerry also knew how to work the media, and when I consider that, it throws a frightening thought into me–that the whole Sixties thing was a media event. Maybe that’s occurred to me once or twice, but I didn’t really want to believe it. It wasn’t uncommon that the media influenced plans for a demonstration, almost in the same way that the New York Times sets the agenda of American politics. The President picks up the paper: ‘What does the Times say? What did I do right? Or wrong, what should I do now?’”

*************

Jerry Rubin’s life played out like a classic three-act play. Maybe it was the drugs, who knows, but at the height of his Yippie rhetoric, he was beyond absurd–one of the greatest Dadaists to ever draw a breath. And depending upon your point of view, he was either infuriating or inspirational–or both. Echoing the sentiments of Che Guevara, he writes in DO iT! “We Yippies are cocky because we know HISTORY WILL ABSOLVE US.”

“We create reality everywhere we go by living our fantasies.”

Throughout the 1960s, Rubin was a contrarian of the first rank: up is down, white is black, rich is poor, “money is a drug.” “Walk on red lights. Don’t walk on green lights,” which is the ultimate irony of Rubin’s existence because on November 14, 1994, Rubin jaywalked on Wilshire Boulevard in front of his apartment building where his impatience to make his way to dinner caused him to be struck by an automobile. Two weeks later, on November 28, he passed away from a heart attack. He died seven months and six days after Richard Nixon.

Fade to black and cue Thunderclap Newman’s version of “Something in the Air” as the credits roll on The Jerry Rubin Story, who lived and died in L.A. Rubin deserves a full-length motion picture (which would have thrilled the All-American boy from Cincinnati, Ohio beyond belief), because people who are ignorant of his bio are missing a big slice of what we call the “Sixties” and what it means to be an activist today. Luckily, the research for the film has already been accomplished with the publication of DiD iT! All that is needed now is a producer with the same kind of cojones as Rubin to step up to the plate and finance what ought to be a David Lean-style epic. It could be huge.

Pat Thomas will appear on Tuesday, September 26th from 6:30pm to 8pm at the Shiley Special Events Suite at the downtown Central Library to speak about Jerry Rubin, show photographs, and play vintage audio clips of Rubin’s interviews and speeches from the Vietnam War era. San Diego author and musician Jon Kanis (Encyclopedia Walking: Pop Culture & the Alchemy of Rock ‘n’ Roll) will help lead a Q&A discussion regarding the cultural impact of Rubin’s personal and political activities. The event is free and copies of DiD iT! will be available for purchase. The Central Library is located at 330 Park Blvd., San Diego 92101 619.236.5800