Featured Stories

Headstock: A Guitar Lover’s Dream

Next month, on November 6 and 7, San Diego will play host to the first-ever Headstock Guitar Lovers Festival. Located in Liberty Station, the boutique trade show will bring collectors and players together with two dozen small-shop luthiers from California and beyond. For the luthiers, the festival is a chance to get their work in front of an appreciative audience, to ogle the competition, and to catch up with one another. For the players, it represents a rare opportunity to see, touch, and hear the current state of artisanal instruments. Included with the Saturday ticket will be evening performances by local guitar heroes Dusty Brough and Peter Sprague.

“We want an intimate little NAMM without the madness,” says Headstock’s co-organizer Scott Bass. “You know those Instagram videos where Eric Clapton is caught at some booth jamming with Stevie Wonder, or whatever? We want to make those happen, but for everybody.”

Bass, a self-proclaimed “garage noodler,” has put on a successful run of surfboard trade shows in California, Florida, and Tokyo. Now he and business partner Pat Hurley hope to do the same thing for guitars.

“The whole trick is to break down the intimidation factor,” says Bass, “and to get people talking, playing, connecting.” To this end, the festival promises panels, small meet-the-luthier talks, a separate amplifier room for plugging in, and lots of short stage performances on the actual guitars that are being shown. Chatting with instrument makers is strongly encouraged. Trying out as many guitars as you can is also encouraged. Just maybe leave your studded belt at home.

And no “Stairway to Heaven,” obviously.

It’s a nice range of guitars represented at this first trade show. Mostly acoustics, but a few electrics. Mostly guitars, but a few ukuleles, mandolins, and even some baroque period instruments. A surprising number of archtop designs, ranging from traditional Gibson-inspired builds to strange curvy beauties that would make Salvador Dalí drool.

None of them are cheap (the majority seem to fall somewhere between $2000 and $16,000, though there are outliers in both directions). But almost all of the represented guitar brands are small or solo shops. If you find yourself talking to someone at a booth while playing a guitar, that someone’s hands probably shaped your guitar. It’s a special experience that both buyers and sellers know can’t be found anywhere else. With luck, it leads to commissions.

“I’m a solo builder,” says Kathy Wingert, a luthier trekking down from Los Angeles. “I’m chained to my workbench many hours a week.”

Wingert builds luscious flat-tops and the occasional harp guitar. But in 20 years of guitar-making, she’s found it’s essential to carve out time for these one-on-one interactions at trade-shows, both in the States and in Europe.

“Attendance at the shows builds confidence that I’m in it for the long haul and I’ll be around to stand behind my guitars.”

“The community feeling at these shows is unlike anything you can experience anywhere else,” says Ryan Thorell, who will be trucking some of his creations in from Logan, Utah. Like most luthiers, Thorell has made many varieties of guitar, but he has a particular gift for modern archtops with surprising sound hole shapes and sloped, floating pick guards.

Ken Minasian is excited for the interchange with his fellow builders as well, though he sees his role as more educator than salesman. Minasian teaches guitar and ukulele-building classes at Palomar College in San Marcos.

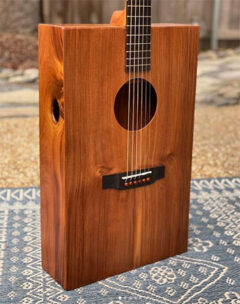

“I’ll bring some different tone woods, some bending forms, some examples of different bracings, and since it’s at Liberty Station, I’ll be bringing my black acacia guitar.”

Minasian encourages his students to take advantage of Palomar’s Urban Forestry program, which recovers local old or downed trees otherwise destined for the chipper and plain-saws them, selling the lumber to students and the public. In 2008, the program picked up a number of old black acacias from right there in Liberty Station. “The wood is shimmery like koa, but darker, with beautiful contrasting sapwood.” Minasian made the back and sides of a flat-top from this black acacia, and even made the bracing from a Torrey pine recovered just up the coast. “If you’re playing it in Liberty Station,” he says, “then you’re playing the most local guitar around!”

For guitar aficionados, wood is a major concern. Collectors have always valued rare, exotic, or especially showy woods like koa or rosewood, and of course the whole larger family of stringed instruments relies on dense, tight-grained ebony for finger boards. Instrument makers everywhere are searching for more sustainable, more reliable, more ethical sources.

“The entire guitar industry represents less than one tenth of one percent of wood use worldwide,” says Scott Paul, Director of Natural Resource Sustainability at Taylor Guitars, “but we are an indicator species. Every single guitar is a nexus of international trade: fretboard from Africa, back and sides from Central America maybe, top from Europe or the American Northwest, bracing and inlay from who-knows-where.” And guitars are sold across borders more than any other wood product, many made in Mexico or China but purchased literally everywhere in the world. No manufactured product captures the overall health and biodiversity of the planet’s forests so conspicuously.

Taylor Guitars has factories in El Cajon and Tecate, Mexico, which together turn out a truly shocking 950 new instruments a day. Watching business grow and wood supplies dwindle, Taylor has become more and more interested in sustainability. Today, the local company owns or supports ethical ebony farms in Cameroon and sustainable koa operations in Hawaii. Taylor is really too big (and employs too many robots) to fit in the boutique company of luthiers at the Headstock Festival. But Scott Paul, who came to Taylor in 2017 after stints with the Forest Stewardship Council and Greenpeace, will be speaking at the Festival in a seminar on sustainable wood sourcing.

A small woodshop can’t hope to shape the industry the way a monster like Taylor can, but there are other tricks.

“I used to call the local green waste log dump my candy shop!” says Ryan Thorell. “When I was young and liked to lift things, I harvested lots of great maple, burl, and walnut from the dump. The small number of guitars that I build allows me to find one of a thing and use it, rather than relying on whole pallets of wood processed for the lowest possible cost.”

“I get sustainable woods from a company in Oregon that specializes in salvage,” writes Greg DeLuis. Based in Los Angeles, DeLuis makes electrics, hollow bodies, archtops, and hand-cut custom inlay. “That’s the great thing about being a small shop: you’re making every guitar from scratch, and so you and the customer can pick out the woods together from what’s available. Then they know exactly what they’re going to get.”

For a customer, the commissioning of a guitar can be an emotional experience. It’s a fair chunk of money, and it’s often a long-held dream realized. A custom guitar is that rare commodity—the holy grail of collectors—an object made without compromises, in other words perfect. In this analogy, the luthier is guide, sorcerer, amanuensis, psychopomp.

“We hope for a synergy among collectors and makers,” says Festival organizer Scott Bass. “Best possible scenario: everyone buys a guitar!”

Here are some of the luthiers, in their own words.

On beginning:

Greg DeLuis: From a very early age, I loved guitars. I remember so vividly when, in high school, I picked up Irving Sloane’s book, Steel-String Guitar Construction, how much it affected me, and basically sealed my fate of becoming a luthier. Even though I was a sculpture major in college and intent on being a fine artist, I always wanted to work with guitars. The chapter on Jimmy D’Aquisto really opened my eyes to the highest form of luthery, which is to say handcrafted guitars as a medium of fine art.

Maegan Wells: “For my small-body archtops, what began as a mission to satisfy the musician that was living inside of me has evolved into serving other musicians in search of the same thing. Turns out that men, women, big and small are all looking for a smaller companion that fits nicely in their arms.”

On automation:

Ryan Thorell: “I have found more spartan ways to express new ideas by forcing myself to accomplish them without machine tooling. For buyers, there is an ascertainable difference in the entire gestalt of the instrument which makes a guitar designed and built by hand one of the most exciting things on the planet… better than a space rocket!”

Kathy Wingert: “I personally enjoy using hand tools more than I like noisy dust makers, but there is nothing wrong with having fixtures and power set-ups for anything that works. I do know that reliance on CNCs and templates can make it daunting to take on oddball projects. A couple years ago, I created something that—to my knowledge—has never been done before: I built a resonator harp guitar. It had four cones, seven sub-basses, and a regular six-string neck. The commission was for it to be in the style of a Rat Rod, of all things. That’s when it makes the most sense to just pick up some tools and start building.”

Greg DeLuis: “I’m not anti-technology in the broad sense, and things like laser-cut fret templates are pretty nice to have. I just really value the romance associated with handcrafted instruments. Sometimes luthiers like me feel like we are recording reel-to-reel in a world of auto-tune.”

On change:

Otto D’Ambrosio: “Musicians and bands used to drive sales of guitars; these days not so much. Most current popular music isn’t played with actual instruments. Hopefully, we can relearn to listen a little more. Trying to find the things that make us feel and act more like human beings and less like algorithms.”

Kenny Hill: “Guitar [making] is a fashion industry, constantly shifting. I make guitars for living in the now, not for some lofty future.”

*******************

November 6-7: Saturday, noon-8pm / Sunday, 10am-4pm.

Liberty Station Conference Center

Tickets and schedule at guitarloversfestival.com