Yesterday And Today

Enlistment Blues: How I joined the Army, met Lester Young and Jo Jones, and found a career in jazz.

Jimmy Cheatham’s memoirs of life in the Army during World War II as told to Jim Trageser. Part Three/Final.

Jimmy Cheatham was head of the UC San Diego jazz program from 1978-2005. He played in Chico Hamilton’s band in the 1960s, also serving as arranger. He also briefly played in Duke Ellington’s band in the early 1970s, while trombonist Chuck Connors was on a medical break. In the 1980s, Jimmy and his wife, Jeannie, hosted a weekly jam session at the Harbor Island Sheraton and then at the Mercedes Room at the Bahia Resort in Mission Bay every Sunday night. The core of the regulars became the Sweet Baby Blues band, which went on to record seven albums for Concord Records. Jimmy died in January 2007.

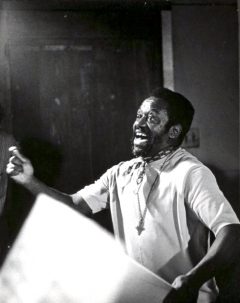

Chico Hamilton in his millitary uniform ca. 1942. Photo: Jimmy & Jeannie Cheatham Collection, University of Missouri Kansas City.

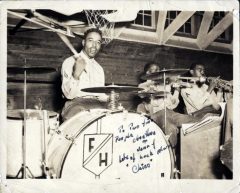

Cheatham’s Jazz Showcase in Buffalo, New York. Jimmy was conductor and arranger; Jeannie on piano, 1959. Photo Jimmy and Jeannie Cheatham Collection, University of Missouri Kansas City.

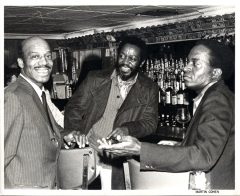

Jimmy with Papa Jo Jones (left) and Jackie Williams, 1970s. Photo: Martin Cohen, University of Missouri Kansas City, Jimmy and Jeannie Cheatham Collection.

As I mentioned, Sax Garrison and Joel Porter were in the band when I joined. And they had played with people like Jimmie Lunceford, Todd Russell’s band, Nat Tolls, Lucky Millinder, and Cab Calloway. Harry “Father” White—he was like a mentor to me—was one of the old ones in the band, and he had been part of the Black Renaissance in New York. He was a trombone player and an arranger for the Cotton Club with Cab Calloway’s band. He also played with Duke Ellington. We got along well together. But Pop White was an alcoholic. It was wild, because he was an alcoholic before he came in the service. At my age, I wouldn’t do that much drinking. I had the whiskey, because I knew how to party. But I would save the whiskey for later on for all those who needed it and then sell it by the pint or the fifth.

Eddie Chamblee, who was with Dinah Washington—he married her and was her music director and tenor player—is one of the few from the band who’s still living. He lives in New York now. When I first joined the band, Chico Hamilton was the drummer. That’s where I met him. I slept on the top bunk; Chico slept on the bottom bunk. He’s older than I am. Chico had probably been in the service about a year before I came in.

Jo Jones didn’t come around until later, around 1945. Jo Jones didn’t come into the band, but he was always with the band, because he was on another type of assignment. Papa Jo did not actually sanction himself coming into the band. But he was always there; he just wasn’t assigned to our unit. In terms of his training, he came to Fort McClellan and he went through all his training even though he was older, in his late 30s. But he went through his training, which was of his own volition. He took his training, and that’s what he always credited for staying as healthy as he did before he died. He had a fantastic sense of dealing with balance. He always challenged himself. So, for him to refuse the training would not be according to his nature and his way of dealing with life. So, he dealt with it and got it over with. But he still maintained whatever that special kind of dispensation was. It seems like he was on kind of a special service type of thing. He was going back and forth between dispatch and mail rooms and things of that nature. He’d go to the PX and he’d play checkers with 24 soldiers simultaneously. And he’d just walk up and down and make the moves. He was there at the band all the time, until something came up where he had to go somewhere. Then he’d be in New York with Buck Clayton, hanging out in New Jersey, and then they’d go up to New York City, record and have a ball. And then he’d come back in on the train. It was very interesting how he utilized his position, according to the people he knew. He was something else. That’s why he became one of my very strong mentors. Because every time he was working with us and talking, I’d be on the top bunk listening and hanging on to his every word. Chico would be on the bottom and fall asleep. Everybody else would fall asleep. And I’d still be hanging and he’d still be talking. As long as you got one eye open, he’d be talking! Papa Jo Jones, I forgot who mentioned it about his playing but said, “Here’s a drummer who plays like the wind.”

And it wasn’t too long after that Lester Young came along.

When Lester Young came, also in 1945, that was when they exchanged the master sergeant for a warrant officer whose name was Gadus J. Hubert. He was also a graduate out of Atlanta University. He used to be a professor at there. He wouldn’t sanction signing up to have Lester come into the band. It was really up to him, and he wouldn’t do it, according to the rumors floating around the band members. We were concerned about trying to get Prez in the band, even with Papa Jo’s coercion. But the resentment was that the warrant officer refused to assert what power he had as a warrant officer to bring Prez, or Lester Young, into the band. Not only that, we couldn’t even requisition him to come and play with the band when we did concerts and things like that, which would have helped, possibly, in terms of exposure. One of the officers might have recognized who he was and might have gone to bat for him. We all declared this to be a chicken shit deal.

Of all human beings, Lester Young should never have been drafted into the service, and especially under the circumstances in which he was drafted into the service, without some due respect for his talent and the chance to let him deal with it in that fashion. And that’s what turned his clock around in terms of his life. I mean, he began to self-destruct for awhile. He was being trained as a soldier, just really nitty-gritty. I would say he was pretty close to 35. The thing is that Lester Young, just from sheer observation of dealing with his persona, should have never been put through what they put him through in terms of Birmingham, Alabama. I can bear witness to that. What happened at Fort McClellan was ridiculous in terms of mistreatment.

But his sergeants, Sgt. Heard and Sgt. Stokes, tried to help him. Whenever they would go out for their training and exercises, they’d march right by the band building. And the band building was self-contained. Not only did we have our rehearsal room and everything there, but we also had our bunks. Whenever they came in that direction heading out to field exercises, the sergeant would march them by the band room and peel Lester right off into the band, and then when they’d come back, he’d pick him back up. So that was some aspect of release in terms of that training. It was kind of mean down there, you see. Lester Young was not a person who could deal with a whole lot of unnecessary aggressiveness. He was a very delicate person. But he could protect himself if need be. It was obvious. You could tell by the way he played. You don’t hear anger in his playing at all. He was almost childlike. He’d come in and speak softly and want to take a shower. That’s what I remember. Naturally, Jo Jones was getting a little closer and talking with him. I would take my G.I. drawers—I had extras—so whenever he would take a shower I’d give him mine so he could have a clean pair to put in his field pack. This occurred with Chico and I several times during Lester Young’s basic training period. Shortly after that, Lester shipped out.

I’ll give a little example of what happened to myself in terms of politics in the service. We were at Ridgley Field, a baseball park in Birmingham. We were playing on a bond tour, a fundraiser to sell government bonds. This was about ’44, ’45. The war bond drives were going strong. There were two military bands, both black; one was from the Air Corps and the other the Tuskegee Air Force Band, which was for black Air Corps pilots. Anyway, they were preparing for this big ceremonial affair, and the officials, strictly Southern, were wearing these big Stetson hats and smoking Cuban cigars. Naturally, to start off the ceremonies we played “The Star Spangled Banner.” While we were playing “The Star Spangled Banner” the white Southern officials were walking around with their 10-gallon hats on and smoking their cigars. After we played it, one of the officials called to us—this is addressed to grown men, military bands— “You boys, you boys play ‘Dixie.’” And naturally, we all looked at each other—you know how that look is when something like that comes in a derogatory manner. Both conductors jumped up and raised their hands to conduct both bands together. And what happened was when they came down with the down beat, our band didn’t say a word to each other! We stood at attention and didn’t play one note. We just stood at attention without sounding our horns. And so the Tuskegee Air Force Band played it. The irony of it was that when we played “The Star Spangled Banner” everyone was walking around talking; it didn’t mean a thing. They didn’t take their hats off or put their hand on their chests or anything. When the Tuskegee Air Force Band played “Dixie,” they immediately stopped, took the cigars out of their mouths, stomped them to the ground, took their hats off and turned to the Confederate flag. We were all saying, “Dig this.” And that was it. That let us know that the Civil War was not over. Here’s a country in a world war and it’s still split. Everybody is supposed to be an American citizen fighting for their country. So that was a phenomenal experience, especially for us because we refused to play.

There were no repercussions from the officials because the song got played. The repercussion came from our master sergeant. Because whenever we did things that he didn’t like he’d let us know. He would always say, “Goddamnit it, I’m gonna instill a little discipline and blah, blah, blah. And remember, I’m your color but I ain’t your kind!” That’s the way he would always talk when he would get upset. And he’d break his little baton! A lot of things he did were from the old school.

I was instrumental in obtaining the orders for the guys leaving when it came time for the discharges. While in the band, I was mail clerk for them. I’d go pick up the mail for mail call. When I went to the administrative headquarters, that’s when I found out that they were beginning to discharge stateside military on a credit system, based on how many years they put in and how much war time they did. Anybody who was overseas was an automatic priority. The statesiders had a certain amount of points. Late in ’45, ’46, that’s when the ruptured ducks began showing up. They called it a ruptured duck because they gave you this little emblem on your insignia, which showed that you were being discharged on the point system.

That day I brought our mail to the warrant officer. So, I’m cooling it during the band rehearsal and everything. After we finished rehearsing, we did the debriefing, news, read letters, and whatever orders we had in terms of administration. I wanted to see if he would mention it. And he refused to mention it! Finally, I said, “Well, look, are you going to tell these guys?” He said, “Oh, yeah.” And then, he didn’t do it again. And so, after the next day, and the next day, finally, I just couldn’t take it anymore. I said, “Oh, there’s one more notice, sir.” And he looked at me real funny, because he knew what was coming. And I mentioned it, I said, “Fellas, I’m quite sure you haven’t been aware because nobody’s talking about it, but we can get discharged—those who are eligible in terms of X number of points, how much time you spent, and what not. And since we’re stateside, we can check it out and look into it and we’ll start working on your discharge.” And they said, “What!” And this was my way of getting back at the warrant officer, because he wouldn’t consider Lester Young, at least in terms of trying to help to lighten his load.

The band couldn’t all be discharged at once, because everybody had different point rates. So that’s where we actually began to see tears and guys hugging each other, because they knew that was it. And everybody started peeling off, you know, going home—happy for each other, but sad because it was like a brotherhood relationship in terms of playing music together. I was actually one of the last to leave because I was one of the youngest to come in. But I had two younger ones come in under me. One was a trumpet player named Clarence Jones out of Oberlin, Ohio, and the other was a trombone and baritone horn player named Andrews out of Baton Rouge. Both of them were fine musicians. Clarence Jones was a fine trumpet player who, when he spoke through his horn, he had almost that same electricity that Louis Armstrong had as a youngster. He didn’t go on to play professionally. In fact, only a few of us did. The only ones who went professionally were Minters Galloway, who was born in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, but he lived in Gary, Indiana, then finally moved to Chicago. I had a chance to join him again in 1950 in Los Angeles. He was living out here and so was Chico at the time, so that’s how we got back together. Minters Galloway since died; in fact, he married Mahalia Jackson. He was a tenor player, played flute and everything. Eddie Chamblee went professional, naturally, because he was professional then. He married Dinah Washington and became her musical director and arranger as well as tenor saxophone player. He was out of Chicago, and he had worked Cleveland, too, in that area. Fortunately, in terms of the ones who are remaining, I’ve had the opportunity to see Ed Chamblee and, naturally, Chico Hamilton and his lovely wife, Helen, plus Everett “Sonny” Curry (clarinet, alto sax, flute) and his admirable wife, Rowena.

With this kind of environment, it was very stimulating. It really set my whole turn of life in terms of what I really wanted to do. And I knew when I got out of the service exactly what I wanted to do, because the other musicians had advised me to take advantage of the G.I. Bill, which I did.

Note: Jimmy’s wife, Jeannie, shared this postscript: “Jimmy used the G.I. Bill to attend the New York Conservatory of Modern Music in Brooklyn, which was run by Al Sculco, a Portuguese gentleman nicknamed “Squeak.” Jimmy finished that school, and one of the fellow musicians there pointed out that he hadn’t used up all his G.I. Bill benefits yet—said he should go to Los Angeles and the Westlake School of Music, on Yucca and Vine. Jimmy developed a close lifelong friendship with one of his instructors there, Russ Garcia. While he was there, he wrote a piece for a string quartet that was premiered at a concert with Paul Robeson. He also received a scholarship to the nearby American Operatic Laboratory. He came back to Buffalo after that, where he met Jeannie—and the rest is history!