Tales From The Road

Collaborating with the Past: Art Garfunkel in the Here and Now

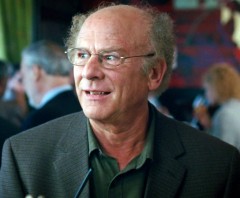

Art Garfunkel

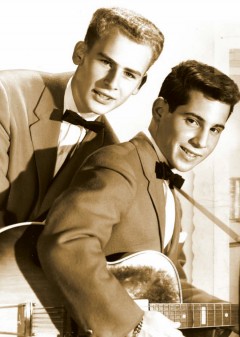

Tom & Jerry in the late 1950s

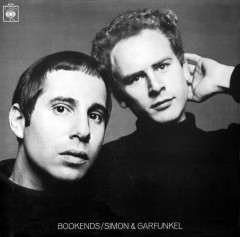

Cover of Simon & Garfunkel’s popular album, Bookends, from 1968

Harmony and dissonance, cooperation and competition: a little of either can go a long way. Most of humanity’s greatest achievements are due to harmonious cooperation and collaboration: collaboration being the result of creating a third thing when you add one and one together. And if popular music is an unflinching snapshot of the epoch from which it springs, there is absolutely no doubt that the simmering, shimmering sound and songs of Simon & Garfunkel reflect the paradigm-shifting restlessness of their time (1964—1970).

Blessed with one of the most angelic voices of the rock era, Art Garfunkel is currently out on the road, paying tribute to the 50th anniversary of the celebrated duo, with a series of concerts titled An Intimate Evening with Art Garfunkel. He performs with guitarist Tab Laven on Friday, November 7, at the Poway Center for the Performing Arts.

Arthur Ira Garfunkel was born on November 5, 1941 in Forest Hills, New York — just three weeks (October 13) after Paul Frederic Simon was born in Newark, New Jersey. They both grew up three blocks from each other in Kew Garden Hills, in the Queens borough of New York, and met in grade school in 1953 when both were cast in a school production of Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland (Simon was the White Rabbit, Garfunkel the Cheshire Cat). The two shared a love for early rock ‘n’ roll and R&B and began singing together in the mid-1950s as “Tom and Jerry” (with Simon on guitar), in a pale imitation of the Everly Brothers. They even scored a minor regional hit before leaving high school (#50 on the Billboard Hot 100) with their song “Hey, Schoolgirl” at the end of 1957.

After Tom and Jerry failed to set the world on fire, the two independently focused on college, with Garfunkel aspiring to become an architect while Simon continued to write songs, flitting in and out of the Brill Building scene. Eventually, the two caught the ear of Columbia Records and in October of 1964 released their inauspicious debut, Wednesday Morning, 3AM. When the LP stiffed, they disbanded, with Simon going to England to pursue a solo career, recording his first solo LP in August of 1965 (The Paul Simon Songbook). When producer Tom Wilson took the “The Sound of Silence” from Wednesday Morning, 3AM and added electric guitar, bass, and drums, without the duo’s awareness, and released it as a single, it quickly became a sensation, going to the top of Billboard’s Hot 100 the first week of 1966. Simon returned to the U.S., regrouped with Garfunkel, and a follow-up LP, Sounds of Silence, was recorded in less than a month, containing the Top Five smash “I Am a Rock.”

A month later another Top Five single was released with “Homeward Bound” and by the end of 1966, Simon & Garfunkel released the innovative Parsley, Sage, Rosemary and Thyme. It was clear that they had grown immeasurably as artists over the course of that year. 1967 was a year of psychedelic transition, with a trio of classic singles: “Hazy Shade of Winter” (#13), “At the Zoo” (#16), and “Fakin’ It” (#23). January of 1968 found them at the absolute peak of form, after Mike Nichols’ featured their songs in his film The Graduate, and they released their artistic watershed Bookends (both LPs went to #1).

Bookends is one of the finest LPs of the 1960s and it showcased what was so special about Simon & Garfunkel: the narrative complexity of Simon’s lyrics combined with an emerging melodic sensibility that stood toe-to-toe with the champions of the day, namely the Beatles. When Nichols offered the duo a chance to appear in his third film, an adaptation of Joseph Heller’s surrealistic anti-war novel Catch-22, it unwittingly served as the catalyst for Simon & Garfunkel to once again go their separate ways in 1969 when the demands of filming interrupted their professional momentum. It couldn’t have helped matters that as Garfunkel gained attention as an actor, Simon’s role in the Catch-22 project ended up being scrapped, later causing Garfunkel to claim that Nichols had unwittingly

broken up S&G.

At a 2013 screening in New York of Charles Grodin’s 1969 documentary about the duo, Songs of America, Grodin said “You don’t take Simon & Garfunkel and ask them to be in a movie and then drop one of their roles. You just don’t do that.”

“Yes, Chuck’s gone right to the heart of the difficulty in Simon & Garfunkel when he says, ‘Artie and Paul were cast for Catch-22, and Paul’s part was dropped,’” says Garfunkel. “I had Paul sort of waiting: ‘All right, I can take this for three months. I’ll write the songs, but what’s the fourth month? And why is Artie in Rome a fifth month?’” Simon responded to the separation by writing the acerbic “The Only Living Boy in New York,” as he waited for Garfunkel to return.

The duo released their final studio effort together in January 1970, Bridge Over Troubled Water, spawning four hit singles: “The Boxer” (#7), the title track (#1), “Cecilia” (#4), and “El Condor Pasa (If I Could)” (#18). It went on to spend ten weeks at number one on the Billboard LP charts and earned six Grammy awards.

There has always been a bit of sibling rivalry between Simon & Garfunkel. Sometimes it comes out jokingly, as when Garfunkel told Nick Paumgarten of The New Yorker that while Simon was born three weeks earlier, technically he was older. “I was conceived first. Paul was one month premature.”

At other times the competition came out bitterly, as in Paul Simon’s 1972 Rolling Stone interview with Jon Landau where he discusses the evolution of “Bridge Over Troubled Water.” “Art didn’t want to [originally] sing it himself,” says Simon. “He felt I should have done it. And many times I think I’m sorry I didn’t do it. Many times on a stage, though, when I’d be sitting off to the side and Larry Knechtel would be playing the piano and Artie would be singing “Bridge,” people would stomp and cheer when it was over, and I would think ‘That’s my song, man. Thank you very much; I wrote that song.’ I must say this: in the earlier days when things were smoother I never would have thought that, but toward the end when things were strained, I did. It’s not a very generous thing to think, but I did think that.”

And therein lies the primary imbalance to the Simon & Garfunkel equation. There is no denying that their voices blend together in such a sublime way, and their close harmonies have a marvelously seductive quality. But no matter how much Garfunkel contributed to the vocal arrangements or their production choices in the studio, it was always Simon who held the creative upper hand by being the sole composer of the intellectual property that the entire enterprise depended upon.

Simon: “During the making of Bridge Over Troubled Water there were a lot of times when it just wasn’t fun to work together. It was very hard work, and it was complex. I think that Artie said that he felt like he didn’t want to record, and I know I said I felt that if I had to go through these kinds of personality abrasions, I didn’t want to continue to do it. Then when the album was finished, Artie was going to do [the movie] Carnal Knowledge, and I went to do an album by myself. We didn’t say ‘That’s the end.’ We didn’t know if it was the end or not. But it became apparent by the time the movie was out and by the time my album was out that it was over.”

************

And then there are times when the duo pokes fun at their public image as bickering ex-partners:

AG: This is Art Garfunkel, formerly of Simon & Garfunkel. I’m here in the studio to talk about something that’s very important to me. You know, a lot of people feel that when an important recording group, such as…

PS: Art?

AG: Yeah.

PS: Let me interrupt you a minute. It’s not quite serious sounding enough. Try to make it a little bit more… grave.

AG: Okay. This is Arthur Garfunkel, once of Simon & Garfunkel. One of the things that’s disturbed me through the years has been people’s reaction to the breakup of Simon and Garfunkel.

PS: Artie? Try and play a little bit more on… emphasize the word “disturbed.”

AG: One of the things that has disturbed me through the years has been people’s reaction to the breakup of Simon and Garfunkel. You know, a lot of people have taken it as a comic event and have not realized that only with deep, real feelings of separate commitment can such…

PS: I like that, I like that part about the “separate commitment.”

AG: Â …can such a breakup actually take place. Only by two, separate individuals pursuing their own individual paths and following, what to them is, the God of their own choice, can two people who were once so close end up…

PS: Art? Art, try and work it in that I’ll be doing a major college tour this fall.

AG: …who were once so close, follow two paths which are so divergent. Whereby, I, for example, record material that I feel expresses my soul, and you, Paul, who are doing a major college tour [laughs] this fall…

— “The Breakup” by Simon & Garfunkel

**************

Simon, of course, went on to record a string of successful albums throughout the ’70s and ’80s, but in many ways it is Garfunkel who took a more intriguing parallel path within his own career as a singer by concentrating on becoming an actor. Mike Nichols’ aforementioned fourth film from 1972, Carnal Knowledge, had Garfunkel holding his own with co-star Jack Nicholson. It contains an interesting passage of Art imitating Life. Or vice versa:

Sandy (Garfunkel): I think I’m in love… I can say things to her I wouldn’t dare say to you. She thinks I’m sensitive.

Jonathan (Nicholson): Sensitive? Oh boy. What do you talk to her about? Flowers?

Sandy:Â Books.

Jonathan: Books? You phony. I read more books than you do.

Sandy: Yeah, well I’m going to start. I’m reading The Fountainhead.

Jonathan: The Fountainhead, what’s that?

Sandy: It’s her favorite book. You ever hear of Jean-Christophe [by Romain Rolland]? It’s a classic, you moron. I’m going to read it right after The Fountainhead.

Jonathan: Yeah? You ever read Guadalcanal Diary by Richard Tregaskis?

Sandy: No.

Jonathan: That was a best seller and I read it. Ever read Gentlemen’s Agreement by Laura Z. Hobson? Ever read A Bell for Adano by John Hersey?

Sandy: I’m going to read everything from now on.

I’m going to read everything from now on. On Garfunkel’s official website he proves how much of a voracious reader he is, not to mention how obsessive compulsive. The Garfunkel Library contains a list, in order of consumption, of every book that Art has pored over since June of 1968. Currently, he has read 1,204 books since the release of Bookends.

***************

By extreme contrast to the rather sweet confections that Garfunkel chooses to record, in 1980 he upped the ante in ballsiness with his portrayal of a chain-smoking psychology professor who is obsessed with Theresa Russell in Nicolas Roeg’s Bad Timing. The film is a delirious mixture of dysfunction and sexual tension, and, along with Harvey Keitel, Garfunkel turns in a performance that

is brave, understated, and effectively disturbing.

However, despite his occasional turns at thespianism, Garfunkel remains foremost a vocalist, even though his voice gave out on him for a while in 2010 due to vocal cord paresis. In a segment for CBS’ This Morning in 2013 he waxed poetic about the loss of his instrument: “I lost my singing voice three years ago; I don’t know how. It has been hard work to regain my sound and to take to the stage again. You need to be brave to mend out in public; so you go to a lower key.”

In March of this year Garfunkel took the time to induct Cat Stevens into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. After running down a list of Stevens’ greatest hits Garfunkel says under his breath, forever the needling sibling, “This guy’s better than Paul Simon…”

In 2012, Columbia Records released a double CD collection from Garfunkel’s entire career titled The Singer. It touches upon the ten solo LPs that Garfunkel has recorded since the breakup of S&G and it recontextualizes Garfunkel’s output, both with and without his famous partner.

As for what to expect from Mr. Garfunkel in the here and now, he told Ken Sharp earlier this year that “I don’t want to make too big a story out of it. It’s not like I’m a walking wounded guy. I’m a singer who had a hiatus because of vocal trouble. I don’t really know what it was. When the doctors looked at my vocal cords they said, ‘One is stiffer than the other and you’re not getting the symmetry you want.’ And I said, ‘I know.’

“You see, singing is very subtle. It’s a lot about finesse and I’ve gone a little cruder in the mid-range where I need to be fine. It was tragic not to be able to finesse the notes like I like to do and I went through a long period of weeping [laughs].

“The rest is prayer, rest, practice… then finally, with fortitude and bravery you have your voice back and you’re pretty much there.”

An Intimate Evening with Art Garfunkel, accompanied by guitarist Tab Laven, will include songs drawn from Garfunkel’s solo LPs, the Simon & Garfunkel songbook, cuts from his favorite songwriters: Jimmy Webb, Randy Newman, A.C. Jobim, readings from his new book, and a Q&A. Friday, November 7, Poway Center for the Performing Arts, 15498 Espola Road, Poway, 8 p.m.