Yesterday And Today

Americana’s First Pure Veteran and Elder Statesman: STEVE EARLE

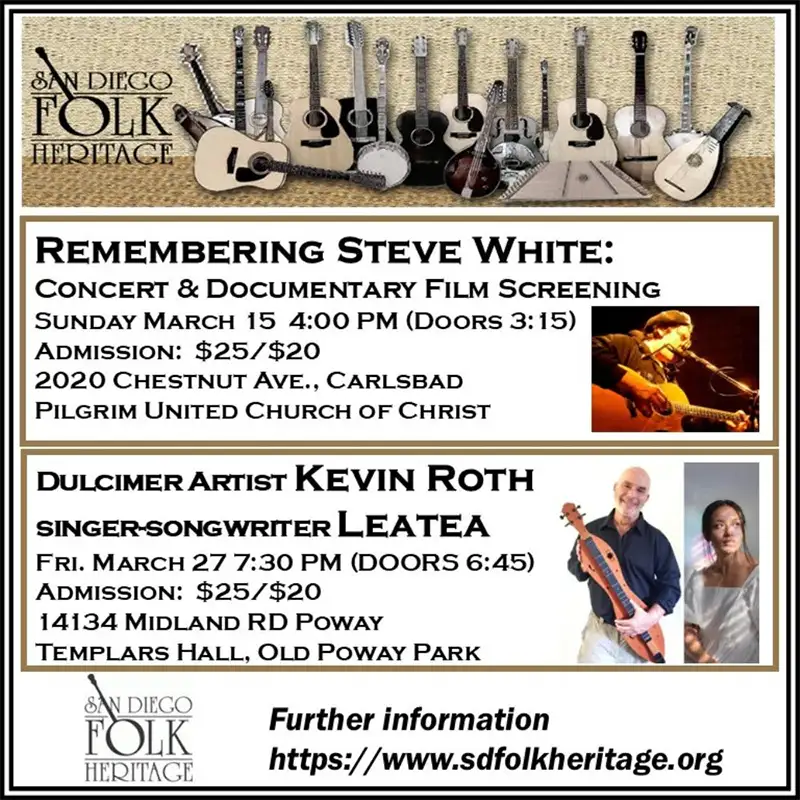

Steve Earle. Photo by Ted Barron.

When Steve Earle came into the world, he was born in Ft. Monroe, Virginia. His father was stationed there as an air traffic controller. When his due date approached, a family member from Texas was dispatched to Virginia with a Prince Albert tobacco tin of Lone Star dirt from the family farm. The dirt was spread into a pan where the newborn was held up to imprint his feet in Texas dirt. The family was then satisfied that Stephen Fain Earle was a true Texan. What followed in his life would further prove he had the grit and guts of a Lone Star native.

When he first came to Nashville it was nearly a decade after good fortunes had found his mentors Willie Nelson, Johnny Cash, Waylon Jennings, and Kris Kristofferson. The singer-songwriters of Nashville had always been an over-populated lot, but by the time of the boom of the late ’60s and early ’70s had petered out, Earle was one among many of empty-handed hopefuls still seeking their success. The kind of songwriters hoping to open doors were a combination of Willie Nelson and Bob Dylan: lyricists, storytellers, and makers of great myths through song. The artists who traveled from Texas also had the memory and often the friendship of the legendary “drunk angel” and possibly the only original songwriting voice of his kind since Dylan was Townes Van Zandt. So what made Earle stand out from the crowd in that now-famous class of ’82?

It was a number of factors, including timing, connections, talent, tenacity, and the fact that Steve Earle was one of those guys that not only had the Almighty breaking the mold when he came out, but he also kicked the pieces as far away as possible so as not to make another Steve Earle again. It seems God knew this guy was going to be a royal, unholy pain the ass. After a 30-year career, not only has Earle stood the test of time, he has also been a key player in changing the course of country music, a force in the creation of Americana music and an inspiration to fans and other musicians when their careers take a nose dive and it seems they’ve lost everything.

Earle first appeared in music history at the end of the Outlaw Movement in 1975, after Willie and Waylon had gone on to their rewards. The film, Heartworn Highway, captured such refugees from Nashville as David Alan Coe and Charlie Daniels throwing the big gigs but also finding time for Townes Van Zandt and Guy Clark as they are followed by a young Earle and his friend, Rodney Crowell in Austin, Texas. The film is an important document that shows how Earle’s own roots were formed at the feet of great poets and songwriters.

Not long afterward, Earle hitched his way out of Austin and into Nashville where little note was made of him until he released an EP. It caught the attention of people in Nashville, but even more notably, it made an impact with many of the legends he had modeled himself on throughout his life. His songs were recorded by Johnny Cash and Waylon Jennings. It became clear that the “outlaw movement” was not quite over, as Earle’s songs made their way around town along with his reputation.

The time when Earle’s reputation and career began has come to be known as the New Traditionalist Movement. It was a rare golden period of music when the roots of country were returned to over easy pop strained sounds. It could be argued that the period from 1982 until 1990 was the outgrowth of the Outlaw Country and the coming of an artistic age of greats like Willie Nelson, George Jones, Tammy Wynette, and Merle Haggard. Earle would later call it the “Great Credibility Threat of the ’80s.” Along with Dwight Yoakam, who had to find his own success by way of the Bakersfield sound in California, Earle was swept into the sweetheart record deals of the day similar to those of the early ’70s when record companies in Nashville, New York, and Los Angeles were willing to put out money on quality songwriters that operated outside the norm of Nashville’s elite and corporately planned successes.

In 1987, with the release of LP debut, Guitar Town, Steve Earle became the center of a storm of artistic talent that was ready to take on Nashville and the entire country scene. But, by the end of the ’80s “Achey Breaky Heart,” Billy Ray Cyrus and the country model boys from hell including the ancestors of today’s sensation the Bobby Rydell-like Luke Bryan, the New Traditionalist movement sadly began to fade and with it any hope of mass success for an artists like Steve Earle, whose follow up releases, Exit O and Copperhead Road sold well but failed to make a lasting impact on Nashville. They were essentially alt-country before there was alt-country. Nashville didn’t know what to do with him. Then came Earle’s own problems with heroin. Eventually, he found himself, like his forefathers before him, in jail with a prison sentence hanging over him. After a few months in prison, Earle elected to complete his term in a Hendersonville Rehabilitation Center where he began his own journey toward sobriety and a new-found success.

Over a decade had passed and when he entered prison and rehab, his career and his fortune seemed completely dried up. But, as a folk-singing poet once said, “There is no success like failure.” In Earle’s case, his failure led to a reconnection with his art and with his career that seemed to be waiting to be dusted off and taken off to the nearest star. As of 1996 with the release of I Feel Alright, which opens with the line “be careful what you wish for/I’ve been to hell and now I’m back again,” Earle was back in full force to produce a series of albums over the next decade that could only be compared to the series of albums produced by Bob Dylan between 1962 to 1969. From I Feel Alright, Earle took his passion lyrically and musically to new heights without regard for genre or commercial sales. He simply rocked. I Feel Alright finds him jubilant in his defiance and his recovery. His recovery was and is clearly serious. There’s no talk of drug or alcohol abuse on the most of his songs over the next few years, but his attitude about the music he produces and its vitality is dead serious and filled with rebellion against the Nashville status quo, which by the ’90s was filled with make-believe cowboys, star-quality model girls with no twang but great outfits and the suits waiting in the wings keep the mediocrity going.

While I Feel Alright, released on his own label, sounded like a debut album, the years that followed produced an album that was stunning, original, dynamic, experimental, and often innovative. Earle came at his themes with diversity and insight attacking political subjects with a daring anti-Reagan, pro-Guthrie-Roosevelt world view that would still be considered fairly radical in today’s tepid and covertly racist and distorted socio-politically polarized world. El Corazon’s songs also brought on Buddy Holly influences drowned in reverb and punk overtones. During the intervening years he lost his friend, Townes Van Zandt, after years of drug and alcohol abuse. The song, “Santa Fe Blues,” perfectly stated Earle’s loss in a deeply personal way. Transcendental Blues fused his rockabilly sensibilities with a late ’60s Beatle-esque style that was surprisingly successful in capturing the roots of rock with the colorful psychedelia of the era. He also came on strong and raw with the politically driven The Revolution Starts Now, his first released in the post 9-11 era, resulting in the artistically risky song, “John Walker’s Blues,” about the American Taliban that takes its narrative from the antagonist’s perspective. The result is brilliant. It was also hard for many listeners to handle anything even remotely sympathetic to the Taliban.

All of this imagination and innovation took place during the rise of the new genre — Americana music — as artists began to rally around the label to help revitalize often flagging careers. It worked as many of the New Traditionalists, like Emmylou Harris, Ricky Skaggs, Lyle Lovett, k.d. lang, and Dwight Yoakam successfully made the transition to the world of Americana, finding newer younger audiences. However, Since Earle’s success was never dependent on an earlier career in country music after his flame out, he has become Americana’s first pure veteran and elder statesmen

Over the last decade, Earle has also been fortunate to witness the emergence of his son, Justin Townes Earle, to critical and success in Americana music.While the younger Earle has made some of the same mistakes as his father, he also appears to have the same tenacious talent and bite that has gifted his elder with so much good art over the years. It’s a thing for a father to be proud of but probably has also engendered some friendly competition between the two artists.

Steve Earle’s more recent albums and projects are so diverse, it’s hard to contain them in one article. Because of his months in prison, he has become an activist against the death penalty. He has recorded three songs, most notably “Ellis Unit One,” for the soundtrack to the Academy Award-winning film Dead Man Walking. He has written a volume of short stories, Doghouse Roses, and a novel that was released with a CD of the same name, I’ll Never Get Out of This World Alive, based on the title of Hank Williams’ last hit song. He has won three Grammy awards, the most recent being 2010’s tribute to his old friend, Townes Van Zandt.

Earle’s most recent release, 2013’s The Low Highway (reviewed this month), follows the same hard-to-break code of his releases over the last 15 years. The title song is striking in that it is almost the antithesis of Woody Guthrie’s “This Land is Your Land.” But, the lyrics, while they illustrate the despair, they always point toward hope:

Heard an old man grumble and a young girl cry

A brick wall crumble and the white dove fly

A cry for justice and a cry for peace

The voice of reason and the roar of the beast

And every mile was a prayer I prayed

As I rolled down the low highway.

If Steve Earle’s story points out anything, the most obvious is the victory of hope and redemption over despair and failure. But, Earle’s story also demonstrates that while an artist may stop drinking or using, their challenges, fight, and rebellious nature could lead to a life of sobriety that is far more risky and edgy than any life of withdrawal into a world of drug and alcohol stupor. Steve Earle is certainly among the most important artists of the Americana movement, but he may also be considered one of the most important artists of this generation.

See Steve Earle with his band, the Dukes, at the Belly Up Tavern in Solana Beach on Wednesday, October 9, 8pm.