Raider of the Lost Arts

Upward Social Mobility

On October 26, 1965, the Beatles received M. B. E.––Members of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire––medals from Queen Elizabeth II during a formal ceremony at Buckingham Palace. They had previously been allowed to perform for her highness at the Royal Variety show on November 10, 1963, but this was altogether different. Whether it was from the enormity of their sheer commercial impact as cultural ambassadors (they single-handedly propped up the flagging music industry through their newly established demographic of JFK-bereaved record-buying fans) or the amount of taxes they subsequently paid into the royal coffers (the “tax exile” archetype wouldn’t emerge until the Rolling Stones’ ascension), the Beatles were the first pop group to be given the award. Though its prestige was thereafter tarnished in some minds, particularly for previous recipients in non-entertainment sectors, the award was an unmistakable sign that contemporary bands and their culturally catalyzing music were being taken a new kind of seriously, and that it was justifiable for one to hope to improve their financial and social status simply by being in a successful pop group. Though John Lennon returned his M. B. E. in 1969, and George Harrison died in 2001, the remaining rhythm section of Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr have since been knighted, are living legends, and are counted among the wealthiest and most famous musicians––let alone people––on the planet, and deservedly so. But one is now hard-pressed to imagine any contemporary artists earning such distinctions (Sir Harry Stiles? Please.). That train has long since sailed.

**************

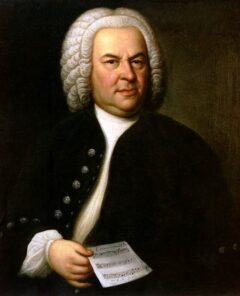

Back in the second half of the second millennium, when it was all about composers and musicians, the former were the only ones who had any shot at an upward trajectory in terms of social standing, lifestyle, and legacy, but it was all contingent on compulsory obtainment of some kind of patronage to even subsist in the arts. Their choices were limited; they either had to take up a parochial position (J. S. Bach did stints as chief organist at various German churches) or secure some kind of royal affiliation or wealthy investor(s)(Domenico Scarlatti was in charge of 18th century Portuguese Princess Maria Barbara’s formative musical education, following her to the Spanish court upon her marriage; Mozart was a child prodigy who performed for royalty and later gained regally affiliated employment in Salzburg; Beethoven enjoyed the sponsorship of Archduke Rudolf of Austria; Tchaikovsky never met his patroness Nadezhda von Meck). And even then, associated with religions, royalty, or wealthy patronage as they may have been, remunerated and honored as they sometimes were, they weren’t necessarily considered to be in the same social caste as their benefactors. When they passed on, their music often endured decades of obscurity, and many of them died penniless, if not drowning in debt.

In the 20th Century, recording technology and the birth and rise of the music, movie, TV, and radio industries changed and expanded the very nature and scope of fame, and subsequently increased the social status of and financial award potential for its participants, who were now able to climb the ladder at least partially through their own efforts. As each fame-fanning industry gathered gravitas, entertainers were able to become just as famous and revered as world leaders, royalty, captains of industry, and politicians due to wider exposure and the increased revenue that came with it.

Subsequently, one could find the first bona fide teen idol––Frank Sinatra––being called “Chairman of the Board” and leader of the Rat Pack, and Elvis Presley became the “King.” Aretha Franklin was the Queen of Soul, and Prince couldn’t have been more aptly named. They met with presidents, cavorted with the upper echelon, and enjoyed lavish lifestyles. Even Sir Mick Jagger, counter-culture royalty and supposed bad boy, has earned a Knighthood. The Beatles convinced an overwhelming majority of consumers to buy entire albums of songs instead of just singles with their working class-cum-landed gentry work ethic and transcendent, galvanizing music. Bob Dylan’s poetic, eloquent, socially relevant song lyrics made him a living legend at such a young age that a significantly vast cross-section of his legion of fans revolted mightily when he changed his sound. Pink Floyd packed arenas––and their personal coffers––with their ’70s string of highly anticipated, reputation-elevating, iconoclastic think pieces.

During the album’s golden age, artists and bands had long, lustrous careers wherein they were allowed to develop to their full potential, becoming prodigiously rich and respected in the process, despite being judiciously exploited by the major labels. And oh, the things they were allowed to get away with during those years! Debauchery, arson, larceny, assault and battery, public drunkenness, possession of illegal substances, destruction of property, statutory rape, etc. All because we saw them as elevated denizens, we gave them carte blanche and enough money to act above the law. It created living legends both ignominious and renowned, and because there was such a disparity between their fantastic and our quotidian reality, we vicariously ate it up, encouraged, and even subsidized it, put them all on a pedestal because of the life-changing work they created. They were the living embodiment of what we dreamed of being, and whom we wanted to be with, criminality and all. They were demigods.

By the early 2000s, the album era had long since peaked, and the nature of fame had begun to shift to something shallower, but the industry was ecstatically bloated, chain-popping bonbons in repose on the settee of unprecedented profits. New CD releases dominated by boy and girl soloists and groups were selling at $15-$20 a pop, and labels and successful acts were all flush and godlike, but the record-buying public was fed up. Enter Napster and the MP3, which reduced the importance of new original music by famous artists through literal and cultural devaluation. Now someone could pay less than a dollar for a song, less than ten for an album, and file-share it for free. Album artwork got reduced to a tiny, ineffectual square, printed lyrics became passé-clutter irrelevant (as did the album format itself), while attention spans, patience for high concept art, and intellects dwindled in parallel with education as school music programs were defunded or entirely cut.

The labels panicked; comfortable and static as they had been for so long, they weren’t prepared––much less willing––to roll with such drastic changes to their cash-cow paradigm. They passed the savings on to the artists, who were no longer allowed to develop under multi-album contracts, could be dropped on a dime despite what were formerly recognized as respectable sales, and were now subject to “360” deals wherein the labels get a share of any and all potential revenue sources (including merchandising, which used to be the main way artists and bands made any significant money they could keep 100% of on tour while struggling to pay off their daunting recoupable costs in the outlandish hope of someday receiving actual royalties).

Image-wise, if an artist didn’t look or otherwise present like they would be a surefire mega-selling juggernaut from the getgo, labels passed. Musical ability became secondary to image, with predictable results in the overall quality of the underlying works comprising the commercial output. The sound quality of the digital files and streaming audio dropped simultaneously, and commercial music was reduced to little more than substandard background noise for the latest movie or video game.

The widespread disregard of innate and refined talent, the resulting lower overall quality of songs and sound, and less revenue potential have made it impossible for any new artists to be ordained and exalted into the zeitgeist, much less able to raise their station or to be seen as anything other than a fleeting flash in a rusted pan. Pop musicians are no longer vehicles for their art; now, the art––which has ironically become way less substantial––is the vehicle for the artist, and in a time when fame seems to have become the primary goal, this is hardly the best crucible in which to nurture noble creative types worthy of idolization.

**************

Pop artists are no longer aesthetic heroes or legends-in-the-making: they are by and large either resting on their established but compromised laurels (though deserved kudos are due to Neil Young and others’ latest actions against Spotify), or ambitious up-and-coming opportunists-cum-overbranded wannabe icons making excessive compromises in their use of a once exalted medium as a stepping stone to opulent glory in other entertainment sectors. Sure, the Beatles made movies too––five, to be exact, with a handful of MTV-presaging promotional song films thrown in for good measure, but as the recent Peter Jackson-directed, excellently edited, and nuanced three-part miniseries of the Get Back/Let It Be sessions show, the Fab Four couldn’t have cared less about the cameras following their every move at Twickenham and Apple studios, especially not while they were creating and rehearsing. There was glorious work to be done, and they showed up almost every day (a justifiably fed-up George Harrison notwithstanding) during normal business hours and created scads of classic music under an insanely tight deadline.

We don’t need to try to imagine how the production and promotion of this film would have been approached by a contemporary cast and crew; the original theatrical release sensationalized and fetishized the drama and tension among the four men comprising a revered yet unraveling institution, telling only a small portion of the larger story as a prime example of what was arguably the first-ever reality show (The Beatles were responsible for a spate of historic firsts, so no surprise there). But when John, Paul, George, and Ringo squabbled, it was polite, and there was a point to it. Most modern reality shows are all sound and fury and much ado, as the pathetic participants sit around in overpriced garments hiding bodies marred by plastic-surgery-abetted anti-aging efforts, get white-girl-wasted at restaurants, clubs, and mansions, and argue loudly about nothing.

The creative moments in Jackson’s Get Back, though occasionally rendered tedious by our knowledge of the end results, are reverentially quiet and serene, pin-drop still despite the exploratory clamor (watch as Ringo silently, raptly looks on), and the viewer is lent the vicarious sensation of seeing a cherished master craftsman at work, slowly carving the block toward its final, magnificent form. One is left with no reason to doubt the wealth and status these artists have earned, and how demeaning it would be to the senses and sensibilities to watch the compositional process of the utterly banal “Watermelon Sugar” unfold in agonizingly slow real time.