Featured Stories

Tippecanoe and Tyler Who? A Brief History of Presidential Campaign Songs

Come join hand in hand, brave Americans all / And rouse your bold hearts at fair Liberty’s call / No tyrannous acts shall suppress your just claim / Or stain with dishonor America’s name.

This is perhaps one of the earliest campaign songs written in 1768 by John Dickinson and titled “Liberty Song,” which was composed eight years before America became a Republic. We already see in these lyrics a sense of what being an American patriot entailed: duty and honor.

After seeing this song in Colonial newspapers, outraged Loyalists responded with their own songs that attacked the lyrics of Dickinson’s. This foreshadowed the future purpose of many campaign songs, which was to serve as attacks directed at one’s opponent:

Come shake your dull noodles, ye pumpkins, and bawl / And own that you’re mad at fair Liberty’s call / No scandalous conduct can add to your shame / Condemn’d to dishonor, inherit the fame.

Throughout the history of U.S. politics, music has been used as a rallying cry, a unifying message and a call to arms for voters. Presidential campaign songs are the commercial jingles for the most important product being sold to the American public: the presidency. Campaign songs have long been the cornerstone of American politics. They applauded the wondrous virtues of each candidate and cautioned of the terrible consequences if he wasn’t elected.

Songs have been used to galvanize support from the public for aspiring presidential candidates since the time of George Washington, who was elected twice. His enthusiasts sang “God Save Great Washington” to rally their countrymen around George Washington. The song dates back to 1786, three years before Washington was inaugurated as president. Ironically, the tune most known among the many lyrical ditties sung on behalf of Washington was “God Save the King.” Of course, instead of singing “King” they substituted Washington’s name in the lyrics. An interesting choice of a song, considering the American colonies had just fought a revolution to rid themselves of the yoke of a King George III. (And the melody was recycled for our national anthem, “My Country, ‘Tis of Thee”).

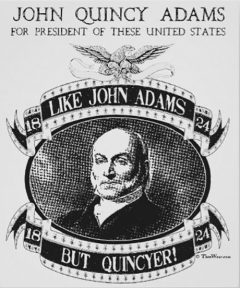

Empty and fulfilled campaign promises are not just part of our generation but they go all the way back to our founding fathers. John Quincy Adams faced a major challenge from Andrew Jackson as the incumbent in the 1828 election. Adams’ “Little Know Ye Who’s Coming” brimmed with lyrical barbs, warning that slavery, pestilence, and even Satan would come should Adams not be elected:

Fire’s a-comin’, swords a-comin’ / pistols, guns and knives are comin’ /… if John Quincy not be comin’.

(Some say that Jackson was one of the greatest president’s this country has elected. Others might just ask the 125,000 Native Americans who were forcibly removed from their millions of acres of land in Georgia, Tennessee, Alabama, North Carolina, and Florida, land their ancestors had occupied and cultivated for generations).

By the presidential election of 1840, political strategists came to realize that songs that extolled some particular virtue of the candidate rather than songs that spoke only about the failings of the opponent resonated with voters much more. Thus, the Whig party in 1840 decided to mythologize their candidate William Henry Harrison with probably the most popular original campaign song (check out the version by They Might Be Giants), “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too.” The lyrics were written by Alexander Coffman Ross, a jeweler from Zanesville, Ohio, in 1840, to the music of the minstrelsy song “Little Pigs.”

What’s the cause of this commotion, motion, motion

Our country through?

It is the ball a-rolling on

For Tippecanoe and Tyler too.

And with them we’ll beat little Van, Van, Van

Van is a used up man

And with them we’ll beat little Van

Like the rushing of mighty waters, waters, waters

On it will go!

And in its course will clear the way

For Tippecanoe and Tyler too

See the Loco standard tottering, tottering, tottering

Down it must go!

And in its place we’ll rear the flag

Of Tippecanoe, and company

The Bay State boys turned out in thousands, thousands, thousands

Not long ago

And at Bunker Hill they set their seals

For Tippecanoe and Tyler too

Have you heard from old Vermont, mount, mount

All honest and true?

The Green Mountain Boys are rolling the ball

For Tippecanoe and Tyler too

Don’t you hear from every quarter, quarter, quarter

Good news and true?

That swift the ball is rolling on

For Tippecanoe and Tyler too

Now you hear the Vanjacks talking, talking, talking

Things look quite blue

For all the world seems turning round

For Tippecanoe and Tyler too

Let them talk about hard cider, cider, cider

And Log Cabins too

It will only help to speed the ball

For Tippecanoe and Tyler too

His latchstring hangs outside the door, door, door

And is never pulled through

For it never was the custom of

Old Tippecanoe and Tyler too

He always had his tables set, set, set

For all honest and true

To ask you in to take a bite

With Tippecanoe and Tyler too

See the spoils men and leg-treasurers, treasurers, treasurers

All in a stew!

For all they know they stand no chance

With Tippecanoe and Tyler too

Little Matty’s days are numbered, numbered, numbered

Out he must go!

And in his place we’ll put the good

Old Tippecanoe and Tyler too

This popular song (a version made it to Off-Broadway in the 1968 musical How to Steal an Election with music and lyrics adapted by folk singer Oscar Brand) was sung long after Harrison died in office a mere 32 days after his inauguration. Harrison’s fame, which catapulted him to run for the presidency,was based, unfortunately, on his mistreatment of the Native Americans (again!). The song references when Harrison, as governor of the new Indiana Territory, negotiated the title to Native lands in hopes that enough whites would settle into the area to qualify it for statehood. These negotiations culminated at the Treaty of Fort Wayne in 1809. Outraged, Shawnee leader Tecumseh preached resistance to the treaty and tried to get Harrison to nullify the agreement. On November 8, 1811, Harrison led stationed troops at Tippecanoe in an attempt to intimidate the insurgent Indians. Undaunted, the Natives charged Harrison’s encampment but were beaten back. After they were forced to abandon their settlement, Harrison’s troops burned the Indian town to the ground. Harrison became ill with paratyphoid fever 32 days after being inaugurated and died. Hence, John Tyler from the song “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too” became the tenth president.

Martin van Buren, eighth president of the United States had his own catchy campaign song (sung to “Rockabye Baby”). Though Buren’s song was not the first to be a contrafacta (songs that use a preexisting—and typically widely known melody—with new lyrics set to it) but it set the trend throughout the 20th century.

Here are two verses:

Rockabye baby, Daddy’s a Whig / When he comes home, hard cider he’ll swig / When he has swug, he’ll fall in a stew / and down will come Tyler and Tippecanoe.

Rockabye baby, when you awake / You will discover Tip is a fake. / Far from the battle / war cry and drum / He sits in his cabin/a-drinking bad rum.

By the mid-nineteenth century presidential campaigns had become like itinerant theatrical shows with various speakers, animals people could ride or pet, floats, choruses, and music ensembles from fife and drum corps to marching bands. Campaigns even passed out free published songsters for the public to take home.

In the twentieth century, Theodore Roosevelt’s 1932 presidential campaign was the first to use a pre-existing song as its unofficial theme song when they selected “Happy Days Are Here Again” from the 1930 Broadway musical Chasing Rainbows. Following Roosevelt, other presidential candidates decided to use already existing popular tunes as their campaign songs. The song “I Like Ike” by Irving Berlin became so popular during General Dwight Eisenhower’s first run for the presidency, the title was put on campaign buttons, posters, and other political paraphernalia. Then Berlin followed up with “I Still Like Ike” when Eisenhower ran for re-election in 1956. The catchphrase “I Like Ike,” became the benchmark that’s still used today in terms of creating a catchy slogan used by political advertisers. For this song and others, Berlin was given a medal by Eisenhower for “his services in composing many popular songs.”

Not to be outdone, John F. Kennedy’s presidential campaign decided to use a popular new song, “High Hopes,” with music by James Van Holden and lyrics by Sammy Cahn. It got its initial fame when Frank Sinatra sang it in the 1959 film A Hole in the Head and won the Oscar for Best Original Song. Cahn took the same melody (contrafacta again!) and wrote new lyrics, with Sinatra (a major advocate for Kennedy) recording the song.

High Hopes

Everyone is voting for Jack

‘Cause he’s got what all the rest lack

Everyone wants to back Jack

Jack is on the right track.

‘Cause he’s got high hopes

He’s got high hopes

Nineteen Sixty’s the year for his high hopes.

Come on and vote for Kennedy

Vote for Kennedy

And we’ll come out on top!

Oops, there goes the opposition – ker –

Oops, there goes the opposition – ker –

Oops, there goes the opposition – KERPLOP!

K-E-DOUBLE N-E-D-Y

Jack’s the nation’s favorite guy

Everyone wants to back Jack

Jack is on the right track.

‘Cause he’s got high hopes

He’s got high hopes

Nineteen Sixty’s the year for his high hopes.

Come on and vote for Kennedy

Vote for Kennedy

Keep America strong.

Kennedy, he just keeps rollin’ – a –

Kennedy, he just keeps rollin’ – a –

Kennedy, he just keeps rollin’ along.

Lyndon Johnson’s presidential campaign saw how well “High Hopes” did with the public and they, too, looked to Broadway for their campaign song “Hello Lyndon” was adopted and adapted from the Broadway hit Hello Dolly. And, at the 1964 Democratic National Convention, none other than “Hello Dolly” star Carol Channing belted out the song in Atlantic City.

Before I finish, I have two more categories of campaign songs I want to discuss: the bizarre and the insincere. One of the most bizarre choices was Ross Perot’s pick of Patsy Cline’s 1961 ballad “Crazy,” which he used in his 1992 presidential campaign. Why would you choose a song about being hopelessly in love—or crazy—to recruit voters? Perot felt it suited him because he said that his opponents just looked at him as a crackpot, so he figured why not stay with the theme of being “crazy.”

There are the presidential campaigns that use an already well-known pop tune even though the artist who wrote it finds the political views of that candidate an anathema to her/his own politics. We have quite the list of songs here, starting with George W. Bush using Tom Petty’s 1989 hit song “I Won’t Back Down” during his 2000 campaign. Bush was forced to stop using the tune when Petty threatened legal action, because he did not give his permission to the Bush campaign that they could use the song and by its use, implying Petty endorsed Bush (he did not). But Bush wasn’t the first candidate to embrace rock n roll—that was Bill Clinton, who used Fleetwood Mac’s anthem “Don’t Stop Thinking About Tomorrow” (with their blessing).

The McCain campaign song for Sarah Palin was Heart’s “Barracuda,” because Palin’s high school nickname was Sarah Barracuda. No surprise here that Heart sent a cease-and-desist letter to the McCain campaign, forbidding them to use the song. Finally, rounding out this brief history of campaign songs, I would be remiss if I did not bring it up to the present time, since we are only weeks away from the presidential election of 2020. Trump’s campaign had been using the Stones 1968 classic hit “You Can’t Always Get What You Want” to close out his rallies, despite the Stones threatened legal action against the Trump campaign if they did not stop using that or any of their songs for his campaign. Trump’s campaign defense was they had the legal right to use the song because it came under the “political entities license,” which allows the public performance of more the 15 million musical works by BMI. However BMI sent a letter to the Trump campaign that said all the Stones’ music had been removed from the campaign license and if they used any of their tunes they would be in breach of its license agreement. Mick Jagger told the BBC, “it is kind of a weird choice for Trump to use the song ‘You Can’t Always Get What You Want.’ It’s a funny song for a play-out song, a drowsy ballad about drugs in Chelsea.” (The Stones are far from alone in threatening the Trump campaign’s use of their songs. Apparently, you can’t always get what you want).

Lastly, I’d like to say it has been difficult for all of us during these Covid-19 times. I, for one, as a musician have missed playing with my fellow musicians in front of a live audience. I always surmised but now I know with urgent certainty how valuable it is for a musician to feel the energy from a live audience. Well, I will have to wait until sometime next year to see you all in a theatre, but I am happy to say Hot Pstromi will get to perform together at the San Diego Rep (Lyceum) Theatre on stage for a Zoom concert Jews, Jazz, and the Whole Shmear on October 29, 7pm. The concert will feature Gunnar Biggs, Tripp Sprague, Fred Benedetti, Kevin Koch, Elizabeth Schwartz, and Yale Strom with two special guests Rebecca Jade (SD Music Awards Artist of the Year) and Broadway star Tovah Feldshuh. Please email Matt Graber at mgraber@sdrep.org for information on tickets and getting the Zoom link.