Featured Stories

The Long Goodbye and the Inevitable Winter that’s Blowing Inside Llewyn Davis

Oscar Isaac as Llewyn Davis

Llewyn Davis and Ulysses, the cat

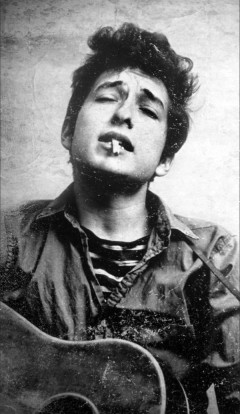

Bob Dylan in 1961

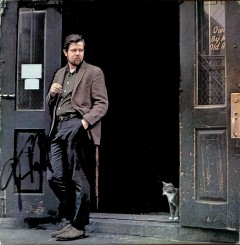

Dave Van Ronk in the early ’60s.

Oh, February!–aka the “death season”–that profound reminder (Ã la “Turn! Turn! Turn!”), where cyclical regeneration comes stealing like a thief in the night. And rightly so — it’s how nature balances its books every year. However, should you find yourself responding to the season with emotional angst, you can always calm that savage beast of a weary psyche with the soothing sound of music. Particularly those organic emanations referred to as “folk music” — that communal repository of ancient yore, dressed up in the finery of ballads, jigs, reels, and dirges — forever championing the grim realities of starvation and deprivation, combined with tales of violent skirmishes that climax in fatalistic dishonor. Ah yes, sharing folk songs together — it’s the perfect way to celebrate winter.

And as much as the above paragraph might be an apt metaphorical reference point for their 1996 film Fargo, the long, cruel winter of discontent continues in the wonderfully wily world of sibling auteurs Joel and Ethan Coen — that dynamic duo whose singular style continues to spiral them ever upwards into the highest echelons of cinema with their latest offering: Inside Llewyn Davis. Painting a world in sensibilities that are barely recognizable by contemporary standards, they have crafted a love letter to a bygone era that stands in stark contrast to now. And what the hell, it’s only been a half century of turning the calendar page for goodness sake. But consider the profound technological changes that 50 years have wrought regarding the way that music is perceived and experienced in our culture. It’s a heavy period of transition that we currently find ourselves in the midst of.

The onscreen chyron hips us to the fact that it’s 1961 at the Gaslight Café in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of New York City. To be even more precise it is the evening of February 17 and performing onstage is folksinger Llewyn Davis. He is finger-picking his way through the folk standard “Hang Me, Oh Hang Me” — sung from the perspective of a man whose luck is about to run out at the end of a rope. The singer is good and his self-assurance with a murder ballad goes a long way toward purposefully establishing tone, because, as should be clear by now, there are no careless gestures or symbolic frivolity when it comes to the carefully plotted universe of the Coens. More to the point, there is a deliberate, epic fatalism scattered like so many leaves throughout the film’s emotional terrain, with our hero perpetually mired in an existential vacuum. And no surprise either, as he futilely hacks away at a folk-singing career of diminishing returns — spending his days and nights conjuring an archaic world through song and strumming endless variations on the themes of murder, loss, and emotional degradation. He’s stranded on the edge of a breakthrough, unable to make the leap at becoming self-aware and fated to repeat this cycle until he figures out how to change it up.

Fare thee well, my honey, fare thee well…

The star of Inside Llewyn Davis is, of course, MUSIC — that magical construct of organized sounds and silences, of notes and words that summon untold mysteries. Central to the enigmatic mystery that’s Inside Llewyn Davis is Davis himself, portrayed brilliantly by the charismatic Oscar Isaac, an unconventionally handsome actor of subtle gifts who also happens to be a sublimely effective musician. Isaac’s Davis is woefully self-obsessed and his inability to connect with a wider audience as a folk singer is mirrored (and exacerbated) by the series of mishaps that unfold throughout his days — days so indistinguishable as to mirror weatherman Phil Connors in the movie Groundhog Day.

Inside Llewyn Davis affords you the opportunity to walk a mile in the shoes of another man, only in this case it is six consecutive days and nights with Davis, shuttling up and down Manhattan and embarking on a fruitless journey to Chicago with nothing to show for the effort but rejection and the impulse to give up on his musical dreams and return to the life of a merchant marine. But life is being so uncooperative at the moment that Davis can’t even score a gig as a seaman and he’s stuck being a folk singer by default.

Central to the plot’s development, of course, are the songs performed throughout, with the libretto serving to emphasize much of the action. Much like Robert Altman’s Nashville, the Coens had the actors arrange and perform their own material live for the film. Music is an important element in every Coen brothers film (thank you, Carter Burwell), but it is particularly crucial to Inside Llewyn Davis. After such a deft series of collaborations on the The Big Lebowski (1998), O Brother, Where Art Thou? (2000), and The Ladykillers (2004), it made perfectly logical sense to once again enlist musician and producer T Bone Burnett to supervise the performances.

“The conversation expands in really interesting ways once we get T Bone involved,” says Joel Coen. “He gets into the story, or the script, and takes it places musically that we wouldn’t have thought of and opens up all of these interesting things.”

On the film’s official website, Burnett shares some of his perspective: “The movie starts out with ‘Hang Me,’ a song about getting hung. And then it goes into ‘If I Had Wings,’ and then you come into Llewyn’s world and you find out that the guy that he performed ‘If I Had Wings’ with jumped off a bridge. And then every song is either about death, abortion, or murder. It’s separation.

“This sounds like something a press agent would say, but I want to say this very soberly. I cannot think of a precedent in the history of civilization for this performance Oscar Isaac gives in this film. I don’t think any actor has ever learned to play and sing a repertoire this thoroughly and compellingly, and be able to film it all live without a click track, without the aid of tuning, without the aid of technology — just a complete analog performance of this character whose music Oscar had never heard a year before he did the film. Unbelievable. Oscar absorbed the guitar playing of Dave Van Ronk and the era — a technique known as Travis Picking — as if he was born to it. He learned all the songs, and he learned to sing ’em so naturally.

“The thing is when we were on the set — in the movie you always have some kind of thumb track or click track or something that sets the tempo so you can cut between takes. But in this case, you know, the Coens decided early on that they just wanted to shoot and record the music live. No playback.”

In addition to Isaac’s superlative performances throughout the film and on the soundtrack, there are also impressive moments by the Down Hill Strugglers, Stark Sands, Carey Mulligan and Justin Timberlake, who really shines in his one big scene on the hysterical novelty pastiche “Please Mr. Kennedy” (as recorded by the “The John Glenn Singers”).

In spite of the legalistic conceit at the end of the film’s credits claiming that there are “no similarities to persons living or dead,” nothing could be more patently absurd. The fact remains that Davis is a fictional amalgamation, like most of the characters in Inside Llewyn Davis, and you can spend a hefty portion of the film’s 105-minute running time playing “spot the doppelgänger,” that literary concept where a paranormal double of a living person exists somewhere in the world. Inside Llewyn Davis is littered with composite characters very much based upon real events and people, with the obvious nod of Davis himself, whose situations are very much drawn from the late, great Dave Van Ronk as he relates in his superb autobiography The Mayor of MacDougal Street. The Coens pay further homage to Van Ronk by having his version of “Green, Green Rocky Road” play over the film’s final crawl. Van Ronk’s true-to-life adventures of being a merchant marine and schlepping off to Chicago in the dead of winter, in a failed bid to audition for powerhouse manager Albert Grossman, is recounted in a sequence where Davis carpools to Chicago with a couple of disenfranchised hipsters (which includes Roland Turner, a verbose junkie portrayed by the consistently superb John Goodman and Garret Hedlund, who plays Turner’s sulking “valet,” Johnny Five). Upon arriving at the legendary Gate of Horn venue, Davis auditions for club manager Bud Grossman (F. Murray Abraham, in a wonderfully callous performance), who tells him after Davis performs a dirge about a queen who dies during childbirth: “I don’t see a lot of money here.”

There actually was a folk singing husband and wife duo in the ’60s named Jim and Jean who recorded for Verve Folkways (Timberlake and Mulligan’s characters respectively). Llewyn’s miserly record label president Mel Novikoff (Jerry Grayson) IS Folkways Records’ president Moe Asch. Columbia records producer Mr. Cromartie (Ian Jarvis) IS John Hammond Sr. And, of course, in the penultimate scene of the film, we have Bob Dylan performing “Farewell,” in yet another echo within this epic tone poem of death and re-birth. The Coens are clearly having a poke in the ribs by taking a folk music purist like Davis (Ã la Van Ronk) and insinuating it is the night that Robert Shelton of the New York Times would show up to write a rave review about the young upstart from Hibbing, Minnesota (the review ran on September 29, 1961). That historical inevitability led to Dylan being signed to a recording contract by Hammond, setting the stage for Dylan’s worldwide, one-man revolution, and allowing him to escape the comparatively low-rent ghetto of Folkways, Electra, and other independents for his ultimate ascent into the big time.

In his memoir Chronicles Volume One, Dylan acknowledges the influence and the debt he owes to Van Ronk: “I’d heard Van Ronk back in the Midwest on records and thought he was pretty great, copied some of his recordings phrase for phrase. He was passionate and stinging, sang like a solider of fortune and sounded like he paid the price. Van Ronk could howl and whisper, turn blues into ballads and ballads into blues. I loved his style. He was what the city was all about. In Greenwich Village, Van Ronk was king of the street, he reigned supreme.” Dylan’s debt ran even deeper after he lifted wholesale Van Ronk’s arrangement of the traditional “House of the Rising Sun” and put it on his own self-titled debut. Van Ronk was miffed but gracious about it and somehow learned to take the matter in stride. It’s a lesson in class that Llewyn Davis would do well to take to heart.

“What are you doing?”

The Coens are the Doublemint Twins of cinema and in addition to the above mentioned doppelgängers there is a “doubling” that runs throughout the film: Timkin and Davis — Jim and Jean, two different tabbys, two sets of dinner guests at Davis’ friends the Gorfeins, Jean’s two other lovers besides her singing partner Jim Berkey, a pair of women (Jean and his sister Joy) incessantly harping on Llewyn, Jean and Roland independently suggesting that Llewyn is living an excremental existence — the symbolic twinning goes on and on. There is even a call back to their previous film O Brother, Where Art Thou? by naming the Gorfein’s cat Ulysses, a reference to Homer’s Odyssey that both films share. And then there’s the film’s ultimate doubling down by repeating the first scene as the last, suggesting in its oblique way that the first verse had come back around as a refrain, which also serves as a final exclamation point to this cinematic Gordian knot. And most assuredly something in the world of Llewyn Davis is coming to pass because each and every breath of this film is spent singing variations on sweet adieu, fare thee well, and goodbye to what has been. Hell, even the last two words of the film are Llewyn saying “au revoir” to the guy from the Ozarks (representing the old guard) who kicks the living daylights out of him for heckling his wife the night before.

Oh, and for all you train spotters out there: as Llewyn nears the end of his cinematic journey he comes across a movie theatre with a one-sheet poster advertising the Walt Disney film The Incredible Journey. Although the novel by Shelia Burnford was published in 1961, it was not made into a film until November of 1963. The adventure of three pets (a Labrador, a Bull Terrier, and a Siamese cat) who travel 250 miles through the Canadian wilderness to return to their home, was no doubt part of the inspiration to include a cat named Ulysses as a central plot device as well.

“You probably heard that one before, because it was never new and it never gets old and it’s a folk song.” – Llewyn Davis

The “Neo-Ethnics” vs. the “Pop Folkies”

Historically, much about the Greenwich Village folk scene hinged on the perception of how “authentic” performers appeared to be – the way they sounded, the way they dressed and how affected was their approach to the material. The type of performers featured on ABC-TV’s short-lived program Hootenanny (1963-64) emphasized the “pop folk” approach, and while that show managed to bring traditional folk songs to a much broader audience, its clean-cut, candyass take on folk music rankled the sensibilities of the “neo-ethnics” like Ramblin’ Jack Elliot, Van Ronk, and others.

Van Ronk: “We knew about the Kingston Trio and Harry Belafonte and their hordes of squeaky-clean imitators, but we felt like that was a different world that had nothing to do with us. Most of those people couldn’t play worth a damn and were indifferent singers, and as far as material was concerned they were scraping the top of the barrel, singing songs that we had all learned and dropped already. It was Sing Along With Mitch and the Fireside Book of Folk Songs, performed by sophomores in paisley shirts, and it was a one hundred percent rip-off. They were ripping off the material, they were ripping off the authors, composers, collectors, and sources, and they were ripping off the public.”

“When you read about the scene you see this mania for authenticity,” says Joel Coen, emphasizing a type of moral stance that many within the folk community felt was imperative. When Bob Dylan stopped writing topical songs adaptable to the civil rights movement (i.e., “Blowin’ In The Wind” or “The Times They Are A-Changin’”), many within the traditional folk community felt a sense of betrayal. That feeling was emblematic of how so many people’s identities were wrapped up in the political correctness of the scene and that folk musicians must retain their social “integrity.” Many of the “neo-ethnic” folkies believed that this ancient language, passed from person to person throughout the ages, held a secret, transformative power and it was not to be trifled with or maligned. Within these circles the politics and the music walked hand in hand. Whether you were fighting for socialism, communism, or civil rights, folk songs became anthems that served as a focal point in the quest for social transformation. But that also begged the question: who are the arbiters of such aesthetics and how does one go about becoming an “authentic” folk singer? For Van Ronk, the answer lay in the record collection of artist and archivist Harry Smith.

Van Ronk: “We were severely limited, because much as we might consider ourselves devotees of the true, pure folk styles, there was very little of that music available. Then a marvelous thing happened. Around 1953 Folkways Records put out a six-LP set called the Anthology of American Folk Music, culled from commercial recordings of traditional rural musicians that had been made in the South during the 1920s and ’30s. The Anthology was created by a man named Harry Smith, who was a beatnik eccentric artist and an experimental filmmaker. Harry had a fantastic collection of 78s and his idea was to provide an overview of the range of styles being played in rural America at the dawn of recording. That set became our bible.

“It was an incredible compendium of American traditional music, all performed in the traditional styles. That was very important for my generation, especially those of us I consider “neo-ethnics,” because we were trying not only to sing traditional songs but also to assimilate the styles of the rural players. Without the Harry Smith Anthology we could not have existed, because there was no other way for us to get hold of that material.”

Moving ahead by looking back

There are some who have suggested, or perhaps it’s only wishful thinking, that Inside Llewyn Davis will spark a brand new folk boom amongst the current generation of music fans. Regardless, for T Bone Burnett, this is what lies at the heart of the film for him: “I don’t want to give a lot away but the film is about a time when there’s a new moment happening. The old has died, and the new thing hasn’t quite been born. We’ve been in an interregnum now for the past ten years, really, where the old has been dying but is not dead, and the new is being born but it’s not yet alive.

“We’ve been in this brackish water where it’s not one thing or another. The old structure that we lived in for my whole lifetime has been dismantled for the most part. But the new structure hasn’t taken place. This is an incredibly long conversation that has to do with everything that’s going on in the Internet and in music. But at any rate, I feel we’re at a time now when the value of music has been brought into question. And this movie speaks very eloquently, I think, about the value of music, and about the value of art throughout culture. We’ve been in a period of time for the last 20 years really, during which there’s been an assault on the arts by the technology community. The technology community has devalued the art, especially music, and has taken over the role of the artist in the society. We’re being told now that artists are to crowd source their work; that artists are to follow the crowd rather than lead the crowd. Well, there’s no artist worth his salt that will follow the crowd.

“I’m not interested in any artist who will follow the crowd. Jules Verne put a man on the moon a hundred years before a rocket scientist did. Einstein said that Picasso preceded him by 20 years. The arts have always led the sciences, and they should, too, because the arts are involved with the whole of humanity, the whole of the creation, not just specific parts of it. We can’t let the engineers be in control of our society because one thing will happen. We will turn into the matrix. So that’s why this film is important to me because it talks about this in a very eloquent way. It’s a much more profound way to talk about where we are.”

Touché T Bone and, once again, hats off to the Coens, who have crafted the ultimate ode of surrender. And may we all learn to gracefully say “adios” to the traditions of the past that no longer serve our evolutionary ascent.