Featured Stories

Robbie Robertson: Fallen Angel of the Six Nations of the Grand River

Robbie Robertson (1943-2023)

He had the vision and drive that gave his Band brothers wheels to ride for years afterward. The first three albums secured his legacy. He wrote and played his way out of Dylan’s shadow and into the heart of American music. —Terry Roland

As we move further into the sunset years of the baby-boom generation, we must witness the passing of our cherished cultural icons. It is an easy temptation to slip into melancholy and even despair. These are hard days of grief and loss.

But, as a lifelong fan of guitarist, singer-songwriter, and co-founder of The Band, Robbie Robertson, it feels somehow wrong to go there as he passes from this life to the next. He has contributed so much to the common musical landscape we’ve walked for the last 50-plus years; it is more fitting to celebrate his life, his work, and the impact he made on his era. For this fan, this has been a time to absorb his music and remember his vision through the songs, recordings, and those timeless voices he helped to release from obscurity: three of the best singers in rock—Richard Manuel, Levon Helm, and Rick Danko. Of course, this is not to discount the musical mastery and wizardry of the great Garth Hudson. Although it would be inaccurate to call him the leader of The Band—though many have identified him in this way—it would be more to the point to give him the title of The Band’s visionary of the heart.

His 1987 eponymous debut solo album opened with a song for his late musical brother, vocalist/keyboardist, Richard Manuel, called “Fallen Angel.” This first song of Robertson’s solo work drew a haunting parallel to the slow, soulful, tear-stained track that began The Band’s recorded legacy on Music from Big Pink, “Tears of Rage,” which Manuel wrote with Bob Dylan. The gateway to Robertson’s solo album is another song of sorrow, “Fallen Angel.” Beginning with the sound of a heartbeat, it transforms into the steady rhythm of a native drum, and then we hear the familiar falsetto that provides a haunting echo of Richard Manuel’s vocal style as it comes through with the cry, “Can you hear me, can you see me?” To which Robertson answers: “If you’re out there, can you touch me? Can you see me? I don’t know If you’re out there, can you reach me? And lay a flower in the snow.”

The legacy of songs and stories Robbie Robertson has left behind is his flower in the snow. Robbie Robertson’s musical journey began at the dawn of rock ‘n’ roll. It was his good fortune that Arkansas rockabilly legend Ronnie Hawkins decided to cross the border from his usual Chitlin’ Circuit to Canada. With drummer Levon Helm and country lead guitarist Fred Carter Jr., Hawkins would recruit a wide-eyed native Canadian teen-age boy as his bass player. Hawkins’ dynamic and outspoken drummer Levon Helm’s recommendation helped. It was from the vantage point of the underage member of a rockabilly band that 16-year-old Robbie Robertson witnessed the birth of rock ‘n’ roll. Ronnie Hawkins was so impressed with Robertson’s songwriting skills that he brought him to the Brill Building in New York City to scout songs for a record. Barely out of his childhood, Robertson traveled through the South as he witnessed a Howlin’ Wolf concert, hosted Bo Diddley, in his hotel room and sat in on a Jerry Lee Lewis recording session at Sun Records in Memphis. He even carried on a brief conversation with Buddy Holly after a show.

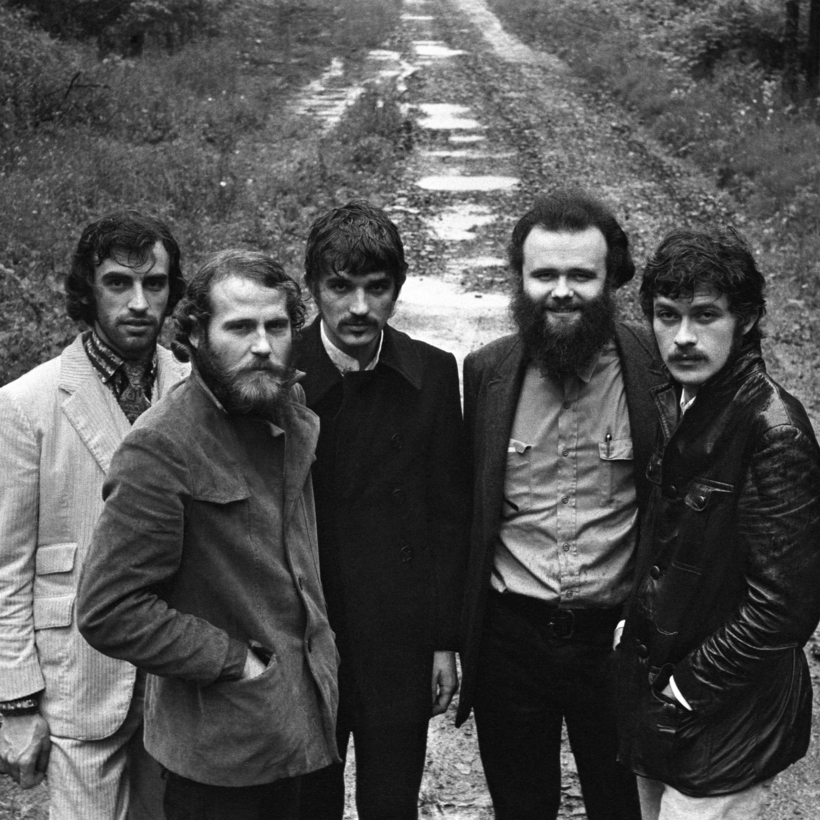

The Band, 1967. L-R: Richard Manuel, Levon Helm, Rick Danko, Garth Hudson, Robbie Robertson. Photo: Elliott Landy.

Soon, Robbie—always eager to learn—became the lead guitar player in the band and formed a close bond with Levon Helm. Hawkins compared them to Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn. This began the nucleus of what was to become one of rock’s great musical outfits. By 1960, they formed a unique band of Canadian brothers they called The Hawks, which included Rick Danko, Richard Manual, and Garth Hudson to complete what may have been one of the most idyllic bands of gypsy musicians to ever come together. Then came Bob Dylan and 1965. The band changed as Robertson and crew learned from America’s greatest songwriter. Oddly, they were universally rejected by audiences on both shores for being a rock ‘n’ roll band backing a newly crowned prince of folk music.

The chaos that followed Dylan and The Hawks throughout their North American and European tours ended in the summer of 1966 with a near-fatal motorcycle accident. But, for Robertson, it was during Dylan’s hiatus from recording and touring in Woodstock, New York, at the house now famously known as Big Pink, that his musical vision became clear. It was a time when Dylan and The Band, took a turn away from the popular psychedelia and rebellious youth movement of the times. Rather, they explored the songs of the past that were rooted deeply in the experience of America’s South from a century before. They did it in a basement. They recorded hours of music, songwriting, and jams that eventually became the stuff of legend. Those sessions, now known as The Basement Tapes, formed the songwriting foundation for The Band’s subsequent three great albums: Music from Big Pink, The Band, and Stage Fright. It also gave Robbie Robertson’s vision the chance to grow. It is what lit the match that inspired him to write such classics as “The Weight,” “Up on Cripple Creek,” and “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down.” While his contemporaries drew their influence from Hank Williams, Woody Guthrie, Leadbelly, and Robert Johnson, Robertson drew from Stephen Foster and Carl Sandburg. Many of the lesser-known songs from The Band’s sophomore 1969 release, The Band, seemed forged from forgotten folk songs and tales of 19th-century America. With the unique acoustic, electric blend and the strength of the musical camaraderie, the album became the vehicle for Robbie Robertson’s songs. The music flowed seamlessly among country, blues, folk, ragtime, early jazz, and gospel. It is truly one of rock music’s rare masterpieces. It became a key influence on today’s Americana-roots music movement, creating a new genre based on songs and styles built on Robertson’s love for the South. It was Robbie Robertson’s vision on songs like “When You Awake,” “King Harvest,” and “Unfaithful Servant” that dug deep into the North American consciousness. The songs seemed like they could have been discovered in a lost American songbook from a century before. The beauty of the music from the era was the harmony and unity that lived among the five musicians. It could not have happened without all of their contributions. Robbie Robertson knew this throughout his life.

For Robertson, as portrayed in the documentary Once Were Brothers, the years of making music with The Band never left the core of his creative work. The series of albums, from his first album to the inventive Sinematic, still bears witness to his vision and brilliance. His brilliant and underappreciated scoring of Martin Scorsese’s films gave a new dimension to his body of work. But the near perfection of The Band could never be replicated, even as the echoes of brilliance in all his music are clear and present. It is a timeless legacy that will not be forgotten. As hard as it is to accept the passing of Robbie Robertson, it’s these flowers in the snow that will serve as a reminder of the soul of his work as we all move closer to darkness and a waiting dawn. Hopefully, among the first sounds we’ll hear will be the steady heartbeat of Robbie Robertson’s music to greet us.