CD Reviews

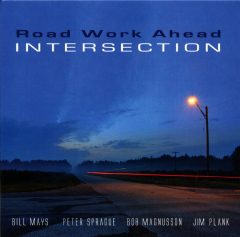

ROAD WORK AHEAD: Intersection

Road Work Ahead is a fairly interesting band among top-flight jazz combos: Born during a 1980s recording session for a Bob Magnusson album, the group has toured and recorded intermittently through the years — always picking up right where they left off, whether it was the night before or a decade earlier.

Magnusson is the Point Loma-raised bassist who, fresh out of school, landed a gig with Buddy Rich, then Sarah Vaughan. Guitarist Peter Sprague is the Tony Gwynn of San Diego’s jazz scene — a first-ballot hall of famer who could live anywhere, but chooses to live in Del Mar except when he’s on tour playing behind Dianne Reeves.

Drummer Jim Plank combined with Magnusson as the house band at Elario’s atop the old Summerhouse Inn in La Jolla, playing weeklong engagements with everyone from Eddie “Cleanhead” Vinson to Harry “Sweets” Edison to Kenny Barron. When KPBS-TV producer Paul Marshall would film the Elario’s artists for his “Club Date” series in the 1980s and ’90s, he kept Plank and Magnusson aboard.

And while pianist Bill Mays no longer calls SoCal home — hasn’t for some three decades — whenever he’s back in the area from his New York base, visiting family, he seems to find time to hook up with his above three colleagues to recast Road Work Ahead, whether for a one-night gig or more fortunately for the rest of us, in the recording studio.

The band’s latest release, Intersection, on Sprague’s Strivin’ to Break Even Records, finds the band’s straight-ahead chops only burnished with the passing years, their copacetic spirit somehow enhanced by the time apart. (Their last album had been 2004’s On the Road Again; the previous two before that had been recorded in the early 1980s.)

Magnusson and Plank are one of the all-time great jazz rhythm sections, their shared concepts of time and meter creating a supple foundation so organic it sounds as if a single person is playing both bass and drums. That solid back end frees up Mays and Sprague to lithely bounce from playing the lead to joining the rhythm section and then go out front again. It’s as seamless a transition from support to starring role as you’ll ever hear.

Opening the new recording, the band turns the Frank Loesser chestnut “Inchworm” (made famous by Danny Kaye) into an uptempo vamp, with Mays extrapolating off the main theme on an extended improvisation before Sprague pulls it back to center. Jazz standards “You Go to My Head” and “The Very Thought of You” get similarly sophisticated, fun treatments before the quartet turns the Beatles’ “And I Love Her” into a samba, with Sprague giving full rein to his Brazilian influences.

The Sprague original, “Wall Street,” is the most muscular song on the album. Aggressive, in-your-face, with Mays’ comping either supporting Sprague’s guitar leads or cutting in front — Mays’ years in New York show in his playing here, which has all the dogged ferocity of someone trying to catch a cab in a Manhattan rainstorm.

“Saudade de Voce,” another Sprague composition, finds the band back in a laid-back samba groove, before switching to a vintage West Coast Cool reading of the Rogers and Hart classic “There’s a Small Hotel” that brings Plank out front for a very introspective, atypical drum solo. The Italian jazz standard “Estate” is classic 1960s straight-ahead small combo jazz, while Mays’ lead on the Magnusson original “Wynton’s Motif” (inspired by the late Wynton Kelly) has the same vintage feel but in a more energetic arrangement.

The album closes out with Plank’s bright arrangement of the David Rose song, “Our Waltz” – again extending the feeling of a classic 1960s jazz summit.

And that’s the overall atmosphere to this recording — not homage or affectation, just four men raised on the sounds of post-swing straight-ahead jazz playing the style as well as anyone ever has.