Featured Stories

Richard Thompson Finds His Voice

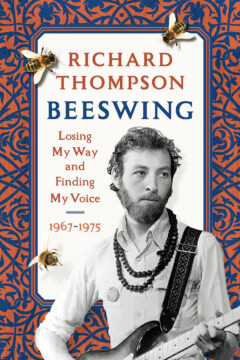

Book Review: Beeswing: Losing My Way and Finding My Voice 1967–75, by Richard Thompson

It seems to be a reasonable expectation that people of genius with extraordinary lives and stories to relate would be able to tell their tale in a manner as robust as the lives they’ve lived. A slight sour truth to accept is that not all extraordinary songwriters are the best narrators of their journeys. My expectations were raised by the revelatory musings of Rolling Stone guitarist and songwriter Keith Richards’ memoir Life, a memoir that was all sex and sizzle and jaw-dropping revelations. Richards’ witty, regaling truth-telling about his life on the edges of rock ‘n’ roll had me insisting that any future musical remembrance be equally careening and in your face.

The demands were cooled considerably by other biographies I’ve read after the vicarious thrill of Richards’ enthused embrace of his wild ways. Bob Dylan’s book Chronicles, Vol. 1 had the Maestro speaking obliquely about his life and influences, but not revealing much that wasn’t already in the dedicated fan’s knowledge base. That wasn’t wholly unexpected, since Dylan has been cagey about talking about his personal life. When he wasn’t making things up, he simply referred to large chunks of his coming of age. Similarly, Jorma Kaukonen wrote about his time as lead guitarist for San Francisco’s iconic Jefferson Airplane in Been So Long: My Life and Music, a memoir of his life growing up in the fifties and thriving as an artist in the swirling ’60s counterculture. His prose was flat, and his feelings influences, friends, politics, and the free-love spirituality of that pugnacious decade are soft-spoken. The detachment from his history made it seem like he talked about someone else’s life and career. Kaukonen, perhaps, would instead have not been charged with writing about them at all.

I suppose the lesson was that although there’s an overabundance of rock stars with stories as horrid, funny, and chaotic as Keith Richards. Some of the stories are quieter in the telling and deservedly so.

Beeswing: Losing My Way and Finding My Voice, 1967–75, a fairly new book by acclaimed Richard Thompson—guitar hero, songwriter, singer, and co-founder of the influential British folk-rock band Fairport Convention. Thompson is appealing and moderate but overly cautious when revealing the facts of his life. Not without sin, sizzle, disaster, or tragedies that need to be overcome as eventual success comes to the music and the music maker. His style is reflective and meditative to a degree, choosing his words and descriptions carefully. There’s also a tangible air of hesitancy while he recounts his story, a seeming concern to avoid the dramatic and the sensational. Too much caution, however, as there are moments where eloquent rumination on incidents would have given Beeswing greater philosophical heft. To this day, it’s one of my low expectations that old guard rock stars have something resembling a pearl of elegant and lengthy wisdom that’s been formed over their years of music-making on an international scale. Thompson is the soft-spoken sort, it seems and the soft-written as well. Elegant in his brief and occasionally minimalist prose, he trades not in scandal, gossip, or revenge snark but rather goes forth like Joe Friday in Dragnet: just the facts as best he remembers them, told as well as he can manage. The album sold meagerly, but it was a fruitful starting point for the legendary band as they progressed. Sandy Denny, a woman blessed with an ethereal and silver-toned voice, replaced original co-lead singer Judy Dyble, Thompson’s girlfriend. The addition of Denny to share lead vocals with singer, guitarist, and songwriter Ian Matthews coincided with Fairport’s burgeoning desire to grow conspicuous American influence but instead explored and made use of their own rich of British and Celtic music folk styles. The following three records—What We Did on Our Holidays, Unhalfbricking, Liege and Lief—marked a band that had invented a new kind of folk-rock, based on a fascinating combination of blues, jazz, and rock filtered through the gossamer textures of British and Celtic melodic construction and overtone. Fired by the unique sensibilities of Thompson’s guitar work, the songwriting collective in this band gave the world that singular thing in pop music history: a distinct body of work.

Thompson doesn’t belabor song meanings or origins nor does he deep dive into the tricks and techniques of his laudable guitar skills, preferring to limn lightly through the scuffling days of the years 1967 through 1975. Again, there isn’t much in the way of sordid detail, strong opinion, or linguistic scene-chewing, but the book does provide a breezy, montage-like feel of Fairport Convention and the bands they knew that gigged in the same towns at the same clubs, pubs, and meeting halls. The elements of low-paying gigs, the band’s eventual adapting an abandoned, unheated pub as band living quarters and rehearsal space, creative tensions in the band, and having a singer in Sandy Denny who was as strong-willed and undisciplined as she was brilliant and alluring are the ingredients of a rich tale that here seems told only by a third. Beeswing has concise and breezy pacing; the book gives off the feeling of being a treatment for a motion picture music biopic. The chronology of events has the air of a “greatest hits” list with the details scantily fleshed out to satisfy the requirements of a screen screenwriter who can squeeze everything into an entertaining and pat 120 feature. After reading, you’re left wanting to know more and can’t but feel a bit cheated.

What might deeper feelings there have been within Thompson when he had to fire Denny from the band? He makes a note of the difficulty in weighing Denny’s great talent against her insecurity and hard-drinking. At this point in a much-detailed story, we witness a conflicted choice to make sure that the band he co-founded remains a stable entity for the sake of his free expression and reason to exist. It’s apparent that as much as he loved Denny and cherished her talent, he felt it better that he and the rest of Fairport move ahead without her. Thompson writes of this deftly but is sketchy on the emotional details. Beeswing is full of matters that cry for a fuller accounting, episodes such as Thompson’s eventual conversion to Sufism, meeting his eventual wife and songwriting-performing partner, encounters, and music with John Lee Hooker, Van Dyke Parks, and Linda Ronstadt. Incidents get mentioned, briefly described, sometimes with significant poetic effect, but too often are a glance at meaningful encounters and musical landmarks. In the end, the style and amount of details are suitable for a making-of-the-band movie or an outline for a limited series for a streaming service. As a book, though, it’s a slight effort often poetically expressed. Thompson has a reputation as a potent lyricist who condenses emotional states and situations to brief, evocative epiphanies. It may be the case that his habit of compositional mind influenced his decision to avoid revealing too much of his inner life. The subtitle of Beeswing: Losing My Way and and Finding My Voice, 1967–75 tells us that the book covers only eight years of the author’s career, hinting that there’s another part of the story to be told, another volume forthcoming. With one book done, it would be a sweet deal if Thompson warms up to the idea that he’s now a writer and composes the next volume fearlessly, with verve, detail, and nuance. Thompson is a magnificent talent, and the world needs him to tell his tale of a critical and endlessly enthralling time in popular music history with the vividness it deserves.