Cover Story

Nobody’s Fool: Jerry Raney Sticks to his Guns

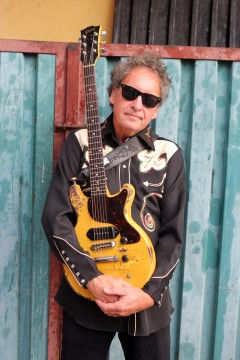

Jerry Raney. Photo by Dan Chusid.

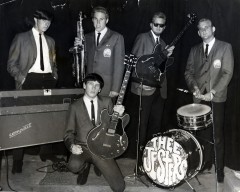

16-year-old Jerry (kneeling) with Thee Jesters, 1964 (Chuck Surface, Steve Sherwood, Larry Tanner, Bob Friedman.

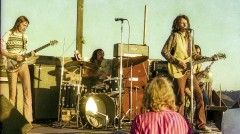

Glory: Jack Butler, Jack Pinney, Jerry Raney, Greg Willis

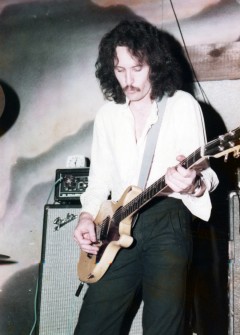

Jerry during the Glory days, 1970

Jerry Raney & the Shames with Jack Pinney and Greg Willis

The original Beat Farmers: Rolle Love, Dan McLain, Raney, Buddy Blue

The Farmers today: Corbin Turner, Chris Sullivan, Joel Kmak, Raney

Say what you will about this tourist trap of a monstropolis that we collectively call San Diego: over the landscape of the last five decades there is no other musician in town that has emerged as such a quintessential by-product of this “destination location” in quite the way Jerry Raney has. In the pantheon of San Diego musicians, the dude has very few peers.

Alternating between a no-nonsense Rayban glare and a goofy, shit-eating grin plastered across his handsome, yet unassuming face, Raney’s been riding on a storm cloud of raw talent, determination, blind luck, and longevity ever since he picked up the electric guitar as a teenager. He attacks his axe with a visceral aplomb that consistently keeps him far above the madding, sun-bleached crowd. In other words, the man just flat-out rocks.

Unless you happen to be underage and unable to get into a nightclub (or have existed primarily in a cave), the odds are pretty well stacked that you’ve encountered Raney at some point between the ’70s and the present day here in town. He’s practically an institution (or perhaps in need of being institutionalized) and he’s been kicking out the jams with an unequaled passion since his days in the mid-’60s as a student at El Cajon High School. Raney remains a supreme example of someone who plays rock ‘n’ roll for keeps, with music as a living and breathing extension of his soul (dilettantes need not apply). Flavors of the month may come and go, but I am beyond grateful that Raney’s relentless rock ‘n’ roll heart keeps pumping up the dance floors and bar rooms of San Diego County. He is truly the real deal, and for anyone unfamiliar with his trip, they owe it to themselves to find out why he’s such an indispensably badass musician.

Raney’s CV is laced with a who’s who of San Diego music lore. In a pique of post-Beatles euphoria, he started out in high school playing in the Perennials and Thee Jesters before mutating into Thee Dark Ages and Glory. A brief stint in the early ’80s as Jerry Raney and the Shames led to snagging the brass ring: co-founding the Beat Farmers in 1983. And for a dozen years, Raney toured the world with the most beloved quartet that San Diego has ever spawned. As a grand testament to their spirit (and a brand that refuses to quit), three-fourths of the original Beat Farmers reunited as the Farmers in 2005, ten years after the untimely death of singer/frontman/drummer Dan McLain (aka Country Dick Montana). Surviving a number of personnel changes (including the passing in 2006 of the incomparable Buddy Blue), the Farmers of 2015 are as strong as ever, and as a testimony to their stealth you can find them rocking out somewhere nearly every weekend at a variety of venues in San Diego. And I can’t detect any waning of energy, between the Beat Farmers at the Bacchanal circa 1986, and how they sounded last Saturday night.

“Yeah, well, that’s the thing: the Farmers are a kick-ass band,” laughs Raney. “I’m proud of my band. And what’s funny about the Farmers now is there are more Penetrators in the band than there are Beat Farmers. Joel Kmak was the drummer in the Penetrators, and Sully [Chris Sullivan] was the bass player.

“People can think what they want to of the band, but we like to play a lot. I kind of force that on the band. I’d rather not sit around and practice these songs all the time. Let’s get out and play in front of people. It gives us something to do. All the wives and girlfriends dig getting out there and the band has a damn good time as well. I mean, we do go out of town and play occasionally, but mostly I maintain the same agenda: let’s get people dancing and be San Diego’s house band.”

************

Born on July 5, 1948, in El Centro, California, Raney was the youngest of four siblings, spending the first decade of his existence in El Centro and Porterville, before moving to El Cajon in 1961 with his mother, brother, and two sisters. “El Centro is kind of a nuts place,” says Raney. “We lived down there since we were extremely poor. I didn’t have a father. I was raised by my mom, but she was on welfare, and we basically starved at the end of every month. We didn’t have anything.

“But being that poor and not having a television was kind of what formed me: I listened to rock ‘n’ roll radio all the time when I was a little kid. K-AMP [1430 AM] in El Centro. I’d fall asleep listening to people call in and request songs. I was so into rock ‘n’ roll, and my mom was a huge Elvis Presley fan, so that sort of molded me. I didn’t really start playing guitar until I was 15, but she would get me to stand up and impersonate Elvis.

“Back then everything was AM radio, and most of the stations would play other music besides rock ‘n’ roll, country/western and crooning-type music: Dean Martin, stuff like that. It took a while before any station was just a straight rock ‘n’ roll station. When I first moved to El Cajon they had a few different radio stations here on the AM dial, KCBQ and KGB. KDEO was another station, they called it “Radio Kay-dee-ooh!” And that was out here in El Cajon. It’s funny, because KGB would have their Top 40 lists and most of the time the Beatles would have the top four or five hits, and they’d always be K-G-Beatles!” he says laughing.

“Right between seventh and eighth grade, we moved to El Cajon. I went to El Cajon Junior High and the first people I met were Lester Bangs, Jack Butler, and Milt Wyatt. Actually, before I even started school, I met Lester Bangs and Milt Wyatt because my mom was going to the Kingdom Hall for Jehovah’s Witnesses, and Lester’s mom was a Jehovah’s Witness and took him there, and that’s where I met the rapscallion.”

They passed you by, overlooked you in some cases

The pretty people, the level chasers

They tried to be part of some scene

The hide and seek that looked down at their feet

Stick to your guns

LB, Stick to Your Guns

Hector the Monkey got you kicked out of school

How could he know they were all so uncool?

Only your friends would try to know your mind

It was the end of being held back in line

Stick to your guns

LB, Stick to Your Guns

It wasn’t long before Raney was in his first rock ‘n’ roll band. “Probably about three months after I started playing I met this guy named Phil Green who had a band called the Perennials,” he says. “Phil was a dang good guitar player for those days. I ended up playing in his band because I could sing and play rhythm and he started teaching me how to play lead guitar. And Jack Butler had been playing guitar for a few years before I started. Butler’s dad hated my guts back then because I had long hair. Gary RÃ chac, his brother, and I were the only longhairs in town. I’d be walking down the street and people would just decide that they were going to stop and beat me up. At first it was ‘Hey, Beatle!’ And then it turned into ‘hippie’ or whatever. But I could hold my own, so it was okay. I had always had long hair, in more of an Elvis style. But when the Beatles came out, I just let it hang.”

Did the Beatles make an impression on you when they appeared on the Ed Sullivan Show?

“Oh, you bet they did. They made an impression on everybody. I was a freshman at El Cajon High School. That was Sunday night [February 9, 1964] and then we went to school the next day, and that’s all anybody was talking about. The jocks were calling them all kinds of sissy names, saying they’re stupid looking. Meanwhile, my friends and I are saying ‘That’s one of the coolest things I’ve ever seen in my life.’ And the girls are saying, ‘Oh, I’m going to marry Paul’ or ‘Ringo is the cutest one!’”

The most recent release in Raney’s extensive catalog are six songs that he and Jack Butler contributed, as Thee Dark Ages, to the 2014 soundtrack for Raul Sandelin’s documentary A Box Full of Rocks: The El Cajon Years of Lester Bangs. The songs serve as a rocking tribute to the late scribe and are full of inside jokes from their days bouncing around at El Cajon High School.

Raney: “I’ve had people come up to me recently and say ‘Wow, was that what Thee Dark Ages sounded like way back when?’ No, that’s Butler and me in his little recording studio and we made those things up at the drop of a hat. I just wanted to write down stuff that reminded me of Lester. Lester used to always sit in with Thee Dark Ages and play harp, and that’s where the song ‘Dark Ages Jam Tonight’ came from.

“Back in high school, Lester told Butler and me, when we were trying to be the Beatles or something, that he had already invented punk rock, in 1965-66. And he said, ‘Everybody’s wearing long hair. You guys should shave your heads and call yourselves the Goons. That’s what inspired ‘They Call Us the Goons.’

LB, Stick to Your Guns: “Coach Foster from El Cajon High hated Lester Bangs. Lester wouldn’t suit up for gym class, and if you didn’t suit up for gym class you would get ten demerits, and you’d have to make up those ten points by writing a page per point about some sporting event. So Lester missed the whole damn semester of dressing for gym, and he comes in and he’s got this book [laughs] and he hands it to me and says, ‘Yeah, I’m giving this to Coach Foster.’ And I look at it and the title is Hector the Homosexual Monkey. And after he gave it to Coach Foster, Lester was gone! [laughs] He wasn’t at gym class anymore. He told me later that that was the coolest thing he ever did because instead of going to gym class he went to study hall and did all his homework and got off an hour earlier than everybody else. So I did it, too! I went to the doctor and told him I was always catching colds and I think it’s because I have to go out and wear those gym shorts. [laughs] So I got out of gym class, too. I learned things from Lester!”

**************

After leaving El Cajon High School, Raney transitioned from the Perennials to another teen combo called Thee Jesters, before forming Thee Dark Ages, who performed regularly at the Hi Ho Club at Parkway Bowl. “The Hi Ho was a great club,” says Raney. “It was as good as the Belly Up Tavern and it was a teenage nightclub. There was an adult’s nightclub called Art’s Roaring Twenties and they took over the space. It was a great building, they had a bunch of other Hi Ho Clubs as well: Riverside, Oceanside, Kearny Mesa, El Cajon, El Centro, and Yuma. And we played all of them at some point.

“Jack Butler and I have always been great pals, and after Thee Dark Ages we formed Glory together. It started off with Greg Willis on bass and Jack Pinney on drums, and initially we called ourselves Blues Messenger. Long before Jerry Herrera had the Spirit Club we were playing at his place, the Palace, across the street from the Sports Arena, before he moved his operation over to [4025] Pacific Coast Highway. When Jerry became partners with Jim Pagni, they changed the Palace to JJs Bar and Grille, and they started putting in a lot more big name people. Glory played some really cool shows there, opening for Howlin’ Wolf, Bo Diddley, Canned Heat. We opened for Steely Dan [March 23, 1974] — it’s probably the only time they ever came through. And we opened for ZZ Top right after Tres Hombres. Butler and me were still playing lead guitar together back then, and we were used to the headliners being a little snotty to us — especially Electric Light Orchestra! [laughs] When ZZ Top came through, we were playing, and all of a sudden from the side of the stage we hear ‘you guys are hot, I love you!’ and I look over and it’s Billy Gibbons, jumping up and down, pointing at us, telling us how much he loved the band.”

While there is scant recorded evidence of what Glory sounded like, in 1973 they released a 45 rpm single, a scorching Raney rocker titled “High School Letter” backed with “Peaches.” A live radio session capturing the band in June of 1970 on KPRI-FM was pressed to vinyl in 2001, offering a unique glimpse into what a tight band they could be, even if the arrangements meandered a bit in the jam band vernacular of the day. Regarding the On the Air session, Raney thinks that “half the album’s not very good; the songs don’t have the right feel. But a few of the songs really get going. There’s that old blues song ‘Another Man Done Gone,’ and we had a version of ‘Who Do You Love?’ and an original called ‘Slow Back.’” The album also features an instrumental of Raney’s with a Latin groove called “Cantaloupe Moon,” a title that would be reprised nearly 40 years later on the Farmers’ 2009 CD Fulmination.

“For about ten years Glory broke up and got back together a bunch of times. Usually because of me or someone else moving out of town. Right after high school we went up to San Francisco for a little while. We ended up using Big Brother & the Holding Company’s rehearsal spot and their equipment. But that was another thing: up there the band just started getting into way too many drugs, and San Francisco had already gone downhill. The peace/love thing was replaced by all kinds of people selling harder drugs in Haight-Ashbury and everything had gotten kind of creepy. And I’m thinking, ‘Well, we’re not getting anything done up here.’ And then the Glory band moved to Portland, Oregon for a while. Then, a couple of the guys came to me and said, ‘We hate it here, we’re leaving.’ [laughs] And I came back to San Diego and I ended up joining the Roosters, which was the house band at the Cinnamon Cinder.

“The Cinnamon Cinder was a big place that used to be a bowling alley, on [7578] El Cajon Boulevard out in La Mesa. Later on it was called Straight Ahead Sound. The Roosters were a Top 40 band that had been together a long time. Their lead guitar player got drafted and their drummer quit, so Jack Pinney ended up being their drummer and I joined on guitar.

“I was feeling pretty hip in those days, and you had to wear a band uniform and they wanted you to do steps. Pretty soon I was saying, ‘I’m not doing these stupid steps, and I’m going to wear a jacket over this shirt if I want to.’ It got to where the owner hated me. But meanwhile, we were providing backup for all sorts of people coming through town, which was a cool thing to do. We backed up the Coasters, the Drifters, and the Shirelles, and shared the bill with Buffalo Springfield when they came to town.

“But I ended up breaking up the Roosters. They had been together for years [even releasing a single on A&M Records in 1964]. It got to where you had to learn almost all of the Top 40 stuff. Although some of those songs were pretty dang cool in those days, it just wasn’t where my head was at.”

***************

During one of Glory’s numerous hiatuses, in late 1969 Raney encountered singer-songwriter Norman Greenbaum, on the brink of enjoying a #3 single with “Spirit in the Sky.” “Yep, it’s all true,” Raney says. “I was looking at the Rolling Stone free musician’s classifieds and saw this ad: lead guitar player wanted for major recording deal. It was a thing where a bunch of guitar players auditioned up in L.A. with just Norman Greenbaum sitting there by himself, and you had to try and follow him with his weird-ass style. I had never heard ‘Spirit in the Sky.’ That was one of the songs that you had to play. There were a ton of guitarists who showed up and I just brought my old Fender concert amp and set it down and sat on top of it and he sat there with an acoustic guitar and I played along with him and ended up getting the gig.

“But afterwards we flew up to Petaluma where he lived on a farm and we were supposed to be putting a band together. And it was kind of funny ’cause he was just NOT a rock ‘n’ roller: he just wrote these little strange folk ditties. And all he really wanted to do was smoke pot and milk his goat. And he didn’t really have things together, and he wouldn’t practice more than a half an hour a day. And I was thinking that there ain’t no way you’ll get a band together like that. So all I was doing was crashing up at his place, totally stranded, and I was getting totally stir crazy. Pretty soon I just said, ‘I’m out of here, take me to the airport.’ If I had to make the decision over, maybe I’d have tried to stick it out a bit longer. I read some interviews later on about how he had trouble [chuckles] keeping guitar players. I knew he wouldn’t make it. He and his producer Erik Jacobsen were so worried about being a one-hit wonder. I kept listening to his other songs that he had written and was thinking, ‘Well, he doesn’t have another song.’ He doesn’t have another song that’s going to come across like this one. And they’re saying ‘No, we’re going to do this ‘Canned Ham’ song.’ ‘When you gonna buy me a Canned Ham?’ I go, ‘What the hell is this?’ Just some kind of weird, little folk song, and he’s making jokes about non-kosher food, and I thought to myself, ‘People aren’t going to get this.’ They tried to put the Black background girl singers on it, like they had on ‘Spirit in the Sky,’” he says laughing. “And it didn’t work at all.”

****************

Of way more significance in Raney’s experience is the afternoon (May 8, 1982) that he and his band the Shames backed up Chuck Berry. “It was one of those KGB Sky Shows at Murphy Stadium. It was actually a big concert, with 50,000 people there. The Shames backed him up and we added Pete Dubow on piano. Cheap Trick was the headliner, with Joan Jett also on the bill. It was a charge, because Chuck Berry and I got along real well. But he wouldn’t tell you what song he was playing, he’d just tell you the key and start playing. I’d look around and go to the other guys “it’s ‘Little Queenie!’ [laughs] And as we were rocking out, he would come over toward me and I’m thinking ‘I’m playing with Chuck Berry! This is cool!’ And then he looks at me and says, ‘Go take a solo.’ So I ran out to the front of the stage and took this solo, which was probably a mix between Chuck Berry and Eric Clapton, and it received a pretty good round of applause. I walked back and he looks at me, and smiles and walks up to the microphone and says, ‘Can that boy play or what?’ And everybody stood up and gave me this big ovation. But after that, no more solos for Jerry though. ‘You go back me up again.’ ‘Yes sir, Mr. Berry.’”

******************

By 1980, after a stint of moving the Glory band to Los Angeles for a series of recordings under a management deal that didn’t quite work out, Raney ended up working in a “porno warehouse” as a shipping/ receiving clerk for a spell. At least that is what he was doing to pay the bills until Willis and Pinney showed up on his doorstep in the aftermath of seeing The Blues Brothers movie. “They told me they were on a mission from God and that they were getting the band back together. And I said, ‘Well, okay, but I don’t want to call it Glory anymore.’ And they said, ‘Let’s name it after you or something.’ So we turned into Jerry Raney and the Shames. At first it was just a three-piece, and then we ended up getting John Baker to join on slide guitar and saxophone. And then Becky Abuer from Becky and the Blue Tones joined: she was a good singer who sounded like Janis Joplin.

“The Shames were trying to get a record deal, and we made a bunch of recordings. I don’t even know what happened to those things. I’m not somebody that keeps things. I was always a real weirdo, let’s face it,” he says laughing.

“Anyway, I’d actually written quite a few songs, but pretty soon I got tired of just playing around. It was starting to bug me that we couldn’t draw more people. We played the Bacchanal one Saturday night as the Shames, which held about 750 people: it was a pretty big place. And I think we had about 250 people in there, but it looked empty. And I just went, ‘That’s it. I gotta stop doing this.’

“But it only took about two weeks before I got this call from Country Dick: ‘Hey Raney, wanna start a musical mobile pleasure unit?’ And that was the start of the Beat Farmers.

“Dick was actually a big fan of Glory. He and his friends pretty much figured out that Glory was the American Rolling Stones, and when he was the junior class president of Grossmont High School he hired Glory to come in and play. And we basically went in there and scared the kids: they were stuck to the back wall, not paying much attention. And then he got up on the microphone and told them that ‘they wouldn’t know good music if it crawled up their legs!’” he says laughing. “It was pretty funny. And then we got banned from the Grossmont School District. Every time the Glory band played a high school, we’d get banned from the district. They used to have free concerts at the Starlight Bowl in Balboa Park, and every time Glory played, people would throw bricks at cop cars and then we’d be closed down. It was like: ‘These guys are too rock ‘n’ roll, we gotta break something!’

“When he called me, Dick was still with the Penetrators at that moment, but he had also struck out and started doing Country Dick and the Snuggle Bunnies. But then that band had just broken up. I was there at Bodies, watching their last show, and Dick was rolling all around on the floor with the microphone: ‘Don’t leave me, Bunnies, don’t leave me!’ So I walked up to him that night and said, ‘The stuff you’re doing is pretty cool, and I think that you’ve got a real good chance of making it.’ And within a few days his mind went ‘Do-ing! Raney’s not playing in a band now.’ So I was the first person Dick called. I didn’t really know Buddy Blue [aka Bernard Siegal] and Rolle [Dexter Love]. I’d seen the Rockin’ Roulettes play; that was Buddy’s band. And he was writing all these songs. And Rolle played stand up bass. He had only been playing for about a year, but he got good quick playing that slap bass.”

As the quartet began to jell, a Name the Band Contest was circulated and the winning entry BEAT FARMERS was supplied by Penetrators guitarist, Chris Davies. Raney: “His prize was a case of beer. Cheap beer!”

The Smell Remains the Same. As the four principals decided to throw in their lot together, they drew up a set list of potential songs to perform and took up residence (at the instigation of McLain) at a puny, East County hole in the wall called the Spring Valley Inn. Fuelled by an endless sea of absurdist humor (increased exponentially by an open bar tab), and a clutch of great originals and covers reflecting the absolute pinnacle of what American roots music has to offer, they started experimenting with the dynamics of their sound and the performance art alter ego McLain crafted for his over-the-top caricature of Country Dick Montana. What the Farmers invented during their stint at the SVI would color and shape the next dozen years (and beyond) of the Beat Farmers’ career. After being together for only a couple of months, they decided to record a demo tape at the SVI for the purpose of shopping it to record labels. Almost immediately, they were enthusiastically embraced by a young A&R guy from Rhino Records named Dan Perloff, who successfully managed to convey his passion to Rhino’s owner Richard Foos that he’d stumbled upon the NEXT BIG THING. To understand what put Perloff into such a lather, you are highly encouraged to check out the 2003 archival CD Live at the Spring Valley Inn, 1983. It just might stand as the primo artifact of the Beat Farmers’ entire career.

“Turn off the jukebox!” There is a distinct “you are there” feeling from this reelin’ and a-rockin’ soundboard cassette recording, with Buddy Blue’s liner notes beautifully conveying the vibe: “Every Friday, Saturday, and Sunday night the band stunk up the SVI for the princely sum of $50 plus all we could drink. And drink we did. Dick would hold court behind the bar, mixing mysterious libations in search of the perfect obnoxicate, and make us pound his proud creations until our heads were in the right place to farm the beat.”

At the SVI the dynamic of what set the Beat Farmers apart from any other band in the universe was immediately established. Live at the Spring Valley Inn, 1983 demonstrates a beautifully crafted bar band blasting out rocking versions of John Stewart’s “Never Going Back,” Elvis’ Sun classic “Trying to Get to You,” and Blue’s kick-ass rockabilly pastiche “Jump Right Back.” So far, so normal: a great, straight ahead, rock ‘n’ roll band. Then, unexpectedly, the drummer lumbers to the lip of the stage, a larger-than-life presence, standing six foot three, in a Wild West trench coat, Bolo tie, and ten-gallon hat, and begins to sing in a rich, basso voice that sounds amazingly earnest and like a total put on simultaneously. You don’t know whether to laugh or cry, or why your jaw is on the floor — it’s such an awesome spectacle. Later, the lurching cowpunk might stroll from table to table or across the bar, swigging and swinging a longneck bottle of cheap beer, spraying himself and anyone in the vicinity. It’s probably the very antithesis of highbrow cultivation, but only a complete curmudgeon wouldn’t allow himself to join in on the fun.

“I called him our secret weapon,” says Raney. “Because we’d get up and we’d play a few songs, and then Dick would just saunter out into the audience and you never really knew what would happen, and we’d just kind of go along with it.”

The Beat Farmers did not attract people who were uptight: you were either able to join in and celebrate the debauchery by diving straight into the center of the dance floor, or you ran screaming in the opposite direction.

Today, Perloff says, “Signing the Beat Farmers was my finest moment. They are one of the great bands. In a perfect world, Jerry Raney would be a huge star.”

******************

After securing the affections and investment of Rhino, the Farmers went into the studio and recorded their debut LP Tales of the New West with producer/musician Steve Berlin of Los Lobos and Mark Linett. Almost immediately, local radio was clamoring to endorse the band and align themselves with these up-and-comers. “Perloff was the guy who pretty much discovered the band,” says Raney. “And that’s where it started, man. Rhino Records, with one promotional guy that just kicked ass. First off, 91X and KGB were fighting over us in the trade magazines. The program director of each station would be writing things: ‘Well, they belong on this station because we discovered them.’ [laughs] That kind of stuff. And ‘They play real music on real instruments.’ That’s what KGB was saying, because they were the regular rock station and 91X was considered more like a new wave thing back then. But they picked a different song; they were playing ‘Reason to Believe’ and all the other mainstream stations were playing ‘Bigger Stones.’ So we had two songs going on the radio in San Diego and then L.A. did the same thing. KROQ was playing ‘Reason to Believe’ and the other one was playing ‘Bigger Stones.’ And as ‘Bigger Stones’ went nationwide, then ‘Happy Boy’ turned into this little, good time, drive-home-from-work-on-Friday song that all the stations, country stations, everything, started playing across the nation. And ‘There She Goes Again’ was popular on college radio. So that was like four songs on the radio at the same time.

“We didn’t know how popular we had become until we went out on the road for the first time. Our manager got us a booking agent and we were off and we were pulling into places like Chicago and just going, ‘Wow, everybody knows us, the place is full, they’re singing along with our songs, we’re doing radio interviews.”

That initial momentum kept the band in the ascent and took them to England to record their second record, the EP Glad and Greasy. The template was firmly established and now the Farmers started looking for broader pastures in which to distribute their wares. Compared to the modest reach of independent Rhino Records (although that would soon change when they merged companies with Warner Elektra Asylum soon thereafter), the Farmers decided to switch labels and moved over to a multi-album deal with MCA-distributed Curb Records in time for their third LP Van Go. On the eve of the LP being released, Blue decided to jump ship and pursue a solo career. Local singer/songwriter/guitarist Joey Harris (of Speedsters and Mentals notoriety) was tapped to fill the vast hole that Blue’s departure created.

Raney: “We loved the Glad and Greasy EP. Buddy was with us when we signed the Curb deal. He quit the band before Van Go got released, but he’s on it. There were a number of things going on. He and Dick weren’t getting along well. But I think the main thing was that he didn’t like Curb Records telling him what he should be doing. Buddy kept looking at it like this should be the band’s songs that we’re recording. Because Curb started pushing for us to listen to songs that their A&R men were bringing to us, and most of them sucked.”

Raney’s “Riverside” from Van Go, became a breakout single and was perfectly suited for AOR radio at the time. Was that by design? “Nah,” he says. “It was just something that popped out of me. I’ve always had this thing when I write songs: I like to get people dancing and excited enough to be moving, and I still feel that way. People recognize that. Jack Butler looks at me and says, ‘My band plays originals and nobody dances to them. You play originals and people dance to them.’ Well, that’s ’cause I have that in my mind: I want to get people moving. And I think if you can get people dancing and not be a sell-out dance band playing disco from the ’70s and ’80s, that’s a real feat. You’re really doing something, and that’s what I like to do.

“I like to stay true to my roots. I’m a stick-to-your-guns kind of person [laughs]; I play the same stuff I did when I was a teenager!”

*********************

From 1986 until 1995 the Beat Farmers toured constantly, putting out albums every couple of years through Curb until the band managed to get out of their seven-record contract in 1993. Their second Act, with Joey Harris, was filled with lots of triumphs: 1987’s The Pursuit of Happiness with the hit single “Make It Last,” 1989’s Poor and Famous, and a sensational live album from the Bacchanal Loud and Plowed and…LIVE!! In 1991, Country Dick was treated for a thyroid condition, but you wouldn’t know it from the band’s appearance on the Late Night with David Letterman program, when they performed Harris’ “Hideaway.” Letterman: “I want to be in that band. I want to travel with those guys. I get the feeling that when they’re traveling, working across the country in that bus, that there may be some states they can’t go to. To me, they’re like a ‘happening’ [addressing sidekick Paul Shaffer]. I love you guys, but if I should have to leave and get a real job, I’m going to work with the Beat Farmers.”

They released two albums for the Sector 2 label: 1994’s Viking Lullabys and 1995’s Manifold. After a dozen years of activity, the entire enterprise came grinding to a halt with the death of Country Dick Montana on November 8, 1995, who suffered a heart attack on stage at the Longhorn Saloon in Whistler, British Columbia. The remaining Farmers dissolved the band three days later.

*****************

For the next decade Raney took up the occupation of laying tile during the day and enjoyed the more conventional domestic tranquility of life at home with his wife, Merrilee, and their two sons, Nathan and Kyle. Raney says that being on the road was tough at times, but that he and his wife managed to survive that period without much tension. “There were times when I’d get home from the road and she’d say, ‘Okay, here’s the kids: it’s my turn to run around. You stay home and babysit.’ ‘Sure, I’d love to.’ It was neat, because I’d be away, but when I got home I got to spend a lot of quality time with the kids. I could take them out during the week because I didn’t have a daytime job. I was a Beat Farmer: I could do what I wanted! [laughs] ‘Do you know who I am? Don’t you know who I think I am?’ Throughout all that stuff, we’ve been married for 38 years. If you find the right person, marriage is easy and it’s good. We love each other, and we have a good time together. I think our interest in music was our actual bond when we first met, because she was really into music.”

Music is obviously Raney’s lifeblood: the man couldn’t keep his hands off a guitar if he wanted to. Working days to pay the bills, Raney continued to pursue his own musical projects in the evenings and weekends. Inevitably these “solo” projects often included ex-members of the Beat Farmers: the Raney-Blue band, Powerthud (Jerry Raney and Joey Harris), and the Flying Putos (Jerry Raney, Buddy Blue, and Rolle Love), which melded into the Farmers by 2005.

Raney: “The guy who used to book the Bacchanal started booking the Belly Up Tavern and he said, ‘Just call yourselves the Farmers,’ and we said ‘okay’ and it stuck from there. Some people have given us crap for it, but the way I look at it is if you’re that disgusted by me calling my band the Farmers or whatever, well you don’t have to come out and see us.”

In 2005, the Farmers (which included drummer Joel Kmak) recorded a CD of superb new material called Loaded. A documentary soon followed by Jamie Dawson titled Pay Up Cheaters: the Story of the Beat Farmers, which does a fair job of relating the history of the band. Then, six months later, on April 2, 2006, Buddy Blue collapsed in his La Mesa living room while playing with his kids and passed away from a heart attack. Soon thereafter, Love decided to step down from the Farmers. Enter Penetrators’ bassist Chris Sullivan, as much a San Diego musical institution as anyone, having also played with Buddy Blue in

the Jacks.

Raney: “After Buddy died, Rolle had pretty much had it. He just told me, at one of the gigs, ‘I can’t do this anymore.’ And so I just called up Sully. Sully had turned up to one of our gigs a few weeks before and Rolle said, ‘Hey, let’s have Sully come up and play a couple of songs. I’ll go out and listen to you guys. I called Sully up and said, ‘Do you wanna join the band?’ ‘Sure, great!’”

The last man to join the current fold is vocalist Corbin Turner, who serves as a sort of tribute as well as doppelgänger for Country Dick Montana, allowing such Dick classics as “Beat Generation,” “California Kid,” “Lakeside Trailer Park,” and “Happy Boy” to be part of the Farmers repertoire. Turner does a understated job of playing the role without turning it into a parody.

Raney: “Rolle’s the one who actually got Corbin going with us because he said this guy can sing the Country Dick songs pretty well. Why don’t we call him up for a couple of songs and just let him do it? And Corbin didn’t really want to do it. [laughs] Rolle kind of forced the thing on him.

“It had been a while since the Shames, where I was the only singer. We built up Corbin slowly. I was still singing more than three-quarters of the songs at first. It’s still a work in progress, really. I want to get it to where he’s singing more than I am. Right now we’re about equal.

“I always said I’m a stick-to-your-guns guy. Hell, other people get up and sing Country Dick songs. Mojo Nixon sings Country Dick songs. If people get pissed off, so what? I’m not going to apologize for anything.”

*******************

Three last questions:

When you were in the eye of the hurricane, having to do a lot of press, was that something you enjoyed?

“Yeah, I enjoy it. I thought it was great when Country Dick and I would go to these radio stations and play off of each other. I can be quick-witted and I can also be a dunce.” [laughs]

Do you think about your own body of work?

“I don’t think about it much, but it’s there.”

You’re still looking forward to the next record?

“I’m ready to do the next record. I think it will be cool.”

I can’t wait to hear it. Make it happen, Captain.