Featured Stories

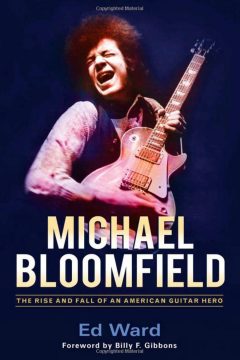

Michael Bloomfield: The Rise and Fall of an American Guitar Hero

Book Review

Those hungering for a history of rock ‘n’ roll’s glory days, à la the Sixties, should latch onto a copy of Ed Ward’s book Michael Bloomfield: The Rise and Fall of an American Guitar Hero. Ward, a longtime music historian and journalist, was one of the original record reviewers in the early days of Rolling Stone. The book is direct, succinct, accurate in detail, and brimming with insights that are breathtaking for their clarity. Ward’s no-fuss, no-frills style serves his subject well, as Michael Bloomfield—arguably the first guitar hero—is a nearly forgotten subject in the discussion of how rock guitar evolved.

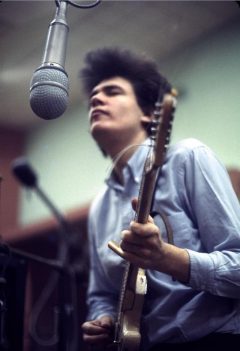

While Eric Clapton has won the praise and glory for his chops when he first appeared on American record stands in 1966 as the featured player on John Mayall’s Blues Breakers album, Bloomfield was already turning heads with this spiky fretwork on Dylan’s 1965 effort Highway 61 Revisited. Dylan had abandoned folk for rock, and Bloomfield was instrumental in creating a new kind of music; it was nothing anyone had heard before. Later that same year, he was featured on the first Paul Butterfield Blues Band record, an integrated band out of Chicago that brought Black blues back into the spotlight.

Combined with Butterfield’s serpentine harmonica work, it was an unbeatable combination, as Bloomfield’s fluid, biting style dominated the disc; audiences and reviewers raved and wrote about the guitarist, not the band leader. Bloomfield was the marvel, the toast among fans and critics, a white Jewish kid from the Chicago suburbs who’d learned his trade from the masters. It’s an old story; somewhat stale as you approach it in order to create a narrative, but it has the benefit of being true in large measure. Bloomfield was that good a musician; he was that important an innovator, his blend of blues-raga-jazz-and traditional was that far ahead of its time. It was a fast rise to the top, a sequence of memorable albums and live dates and then a long slide into a comparable obscurity. Ward makes the case that Mike Bloomfield is an artist whose influence is still very much felt today although his name is not often mentioned.

Ward accomplishes setting up a story of the young Bloomfield, a young man who grew up in the Chicago suburbs and the son of a successful businessman, discovering the blues and seeking out the musicians who played it: Muddy Waters, Hubert Sumlin, and B.B. King. Always restless and impatient with his own progress, Bloomfield jumped between many styles—from Chuck Berry rock ‘n’ roll to Chicago Blues, country blues, and jazz, learning the riffs, phrases, and the subtle embellishments of each style. Particularly fascinating are the variety of circumstances in which he became acquainted with other white musicians obsessed with Black blues music, in the persons of Paul Butterfield, Nick Gravesites, and Charlie Musselwhite.

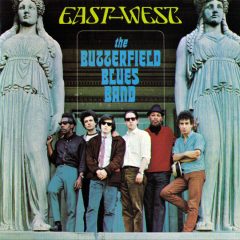

In quick succession the guitarist was in the spotlight for his work with Dylan and the acclaim he drew for his blistering fretwork on the first Paul Butterfield Blues Band album. With the release of that band’s second album, East/West, the consensus seemed to be that Bloomfield was the finest guitarist on the planet, with the band in large measure leaving the traditional blues styles they’d been interpreting behind and extending themselves with long improvisations. Key to this was a swinging workout on Nat Adderley’s “The Work Song” that was elevated by Bloomfield’s fluid single note lines. But what sealed the deal on Bloomfield’s reputation was the title track, a 13-minute raga/drone improvisation influenced by John Coltrane’s integration of Indian classical music techniques into his register-jumping flights. The center of the piece was Bloomfield, extemporizing in a manner that was a curious but entrancing mixture of both his jazz and raga influences; this was the guitar solo that raised the bar perilously high for other players.

Ward goes through the highlights and low points of Bloomfield’s career, using a series of effectively placed quotes from those who knew and worked with him to provide context to the problematic musician’s life. He was a manic personality, perpetually ill at ease, starting projects and abandoning projects in quick order, blazing through stints with Butterfield, Electric Flag, Muddy Waters, Al Kooper, KGB, John Hammond Jr., and Dr. John. There were so many promising starts, so many abrupt departures. Audiences took him for granted; critics started awarding him negative reviews. By his own admission, Bloomfield’s heroin use eroded his skills as a guitarist to the extent that he ceased playing altogether for a period. Ward details the effects of drugs on his work, and admirably resists the urge to sermonize, lecture, or otherwise wring his hands over the murky circumstances about Bloomfield’s death from a drug overdose in 1981. The tragedy—the loss of a gifted musician too early in his life—is effectively conveyed through the way Ward has laid out the progress of Bloomfield’s life of music making, from a naïve but engaged kid from the suburbs seeking out his heroes in the bars of Southside Chicago to an artist making his way through the mad eddies and inviting distractions of the Sixties counterculture. Detailed, perceptive, free of babble and cant, Ward comes not to sensationalize this life but to celebrate the music Michael Bloomfield played, a blues that all these decades later still moves the soul and warms the heart.