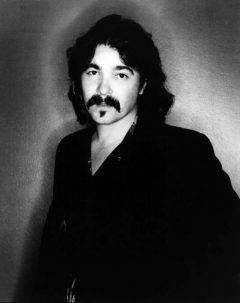

Yesterday And Today

John Prine: American as Plain Speech

I’m very sad by the passing of John Prine, a wordsmith who managed the hardest of all lyricist obligations: to be plain-spoken, colloquial, and unafraid. His best songs have an authentic, unaffected quality, that of someone talking about some odd thing that happened to them, recent or in the past, setting a scene, establishing an attitude and a personality at the beginning of the story, giving you an idea of where he was going with it all, an idea of what the moral of the tale would be, but then he concludes or at least stops his story at some point you didn’t expect. He could be colloquial without being unclear, idiomatic without resorting to cracker barrel cliches; this was someone you knew perhaps not intimately, but whom you knew well enough to have an ongoing conversation about the weather, sports, women, bad jobs, celebration and tribulation and come away with a feeling that you had just tapped into a larger Life Force. This writer wasn’t, though, a preacher or a saint or an expert, or at least not an expert on anything beyond his experiences and the blessings or consequences of them. He didn’t “drop knowledge”, he didn’t advise, he didn’t moralize. He just told you what he knew and admitted what he didn’t know and leave you a strong inclination to lean closer and observe longer and perhaps glean some incidental insight as to how to remain teachable after you’ve learned all the answers. That was a huge part of my attraction to his music and lyrics, their complete lack of pretension.

Prine was less a poet (capital “P”) than were some of his contemporaries, than he was a story teller, but with the sense of structure of a great short story writer like John Cheever or Raymond Carver. John Prine was a romantic with good sense of the hard, real ground even the dreamers have to walk. He was a fatalist who could accept either a good or bad hand dealt him by a world that paid his expectations no mind. But he wouldn’t dive into a murky, sticky self-pity, a critical flaw in many a singer/songwriter’s work. Jackson Browne, for example. His music was such that it revealed a well-balanced ambivalence to circumstances and outcomes. He kept a sense of humor, allowing for the events of his life mature into a genuine wisdom. He continued to pursue his calling. Prine wasn’t a happy-go-lucky naif nor was he cheery when matters hit the skids or if his expectations weren’t met. He acknowledged his feelings; he would pause and rise to his feet after awhile and continue on his path. An element of his tales, his loves and heartaches is this mastery of the Long-View, the unexpected but welcome shift in perspective that provides what the lesson was of experience, if there was any. Nothing preachy, nothing of the old-man attempt toward wisdom drawn from travels and travails. Prine sounded like he was talking to you, in a living room, over lunch, at a bar, over a backyard fence. And, as I said, he had a sense of humor. He has a song called “When I Get to Heaven” from his 2018 record The Tree of Forgiveness:

When I get to heaven, I’m gonna shake God’s hand

Thank him for more blessings than one man can stand

Then I’m gonna get a guitar and start a rock-n-roll band

Check into a swell hotel, ain’t the afterlife grand?

And then I’m gonna get a cocktail: vodka and ginger ale

Yeah, I’m gonna smoke a cigarette that’s nine miles long

I’m gonna kiss that pretty girl on the tilt-a-whirl

‘Cause this old man is goin’ to town

Then as God as my witness, I’m gettin’ back into show business

I’m gonna open up a nightclub called the Tree of Forgiveness and forgive everybody ever done me any harm

Well, even invite a few choice critics, those syphilitic parasites

Buy ‘em a pint of Smithwick’s and smother ‘em with my charm

‘Cause then I’m gonna get a cocktail: vodka and ginger ale

Yeah, I’m gonna smoke a cigarette that’s nine miles long

I’m gonna kiss that pretty girl on the tilt-a-whirl

Yeah, this old man is goin’ to town

Yeah, when I get to heaven, I’m gonna take that wristwatch off my arm

What are you gonna do with time after you’ve bought the farm?

And then I’m gonna go find my mom and dad, and good old brother Doug

Well, I bet him and cousin Jackie are still cuttin’ up a rug

I wanna see all my mama’s sisters, ‘cause that’s where all the love starts

I miss ‘em all like crazy, bless their little hearts

And I always will remember these words my daddy said

He said, “Buddy, when you’re dead, you’re a dead peckerhead’

I hope to prove him wrong… that is, when I get to heaven

Cause I’m gonna have a cocktail: vodka and ginger ale

Yeah, I’m gonna smoke a cigarette that’s nine miles long

I’m gonna kiss that pretty girl on the tilt-a-whirl

Yeah, this old man is goin’ to town

Yeah, this old man is goin’ to town

This is the greatest of all American literary personae—the knowing hick, the bucolic philosopher, the country ironist, a figure that is from Mark Twain straight up to Richard Brautigan and Kurt Vonnegut. An unlettered man, apparently, he has an indefatigable self-confidence and Panglossian who, aware that he is dead and in the clouds with his Creator, shakes His hand and sets out to do what a heaven of his imagining would be, to have his favorite cocktail, smoke copious amounts of cigarettes, stick to his nettlesome critics by compelling them to sit through his nightclub act, reunite with this family, not for tears and regrets but for good times and real love… You can go through his catalog of songs and parse his lyrics any number of ways and marvel at the sweet subtleties he created with such clear, unmanned, and un-fussy language. He was an Everyman who was appealing because he wasn’t trying to impress anyone or blow them away with Big Stories with a Big Message, messages that were rather hackneyed, à la Harry Chapin. Prine’s ambition seemed not much more than to be the best songwriter he could be, someone surprised that a great many others over the years admired his rich body of work

(Friend, author, and cultural historian Barry Alfonso weighs in)

BARRY ALFONSO: I concur with your view that Prine did not foist pre-chewed wisdom upon his audience and didn’t tailor his song-stories to fit an agenda. If he was telling you what he felt was the truth, there was no self-righteousness about it—he seemed more saddened than pleased that he was right about the commonplace cruelties of the world. I do disagree slightly with your closing thought that Prine was “surprised that a great many others over the years admired his rich body of work.” While he did carry himself with a humble air, I think he was intensely ambitious and thought quite highly of what he was doing, as he should have. I can tell you that Prine was truly loved and deeply admired by the Nashville songwriting community. Like Townes Van Zandt and Guy Clark in different ways, he set a high standard, many aimed for but few could reach. He easily could have slipped into obscurity when his sort of intelligent rustic folk balladry slipped out of commercial favor in the mid-’70s. Instead, he started his own record company when very few artists did so and continued to write enduring songs that spoke about real things with unaffected eloquence. He sang in plain speech, but he wasn’t afraid to be weird and prickly and stubborn as a mule in Paradise. As much as he was a man of the people, there was still something of the underground subversive and incurable iconoclast about John Prine, flashing his illegal smile when the smug and well-heeled weren’t looking.

TED BURKE: I actually meant that he was the sort of man of considerable gifts as a writer who was more interested in the smaller, less grand conclusions of what the respective meanings of his life would be, and that he made me think of the sort of person who was genuinely gratified that others, listeners, and other writers, found his work particularly good. That was more a line about his persona, not actual fact. From what I’ve seen and read about him, on old TV shows and in interviews, he knew how good he was; at the end of the day he was a professional with a good estimation of his talent as well as his audience. The appeal was that he didn’t lord it over anyone. He was what he was and you could hang with it or find another playground. And it is that undercurrent of contrarianism, that willingness to subvert assumptions of what plain language—or our collective fantasy of what “plain speech” might be—and merge the working class idiom with an extraordinary ability to note when remarks and deeds were not congruent and consistent, a skill that was acute, yet subversively applied. Yeah, I would agree that he seems like the guy who walks into a room spun out on that day’s meth, marijuana, and vodka, who grinned like he had read everyone’s score card and had a sense of who’d make it through Heaven’s Gate. Whether he did or didn’t wasn’t revealed and, finally, wasn’t important. You leaned in closer to hear him and found someone who delightfully confounded expectations.